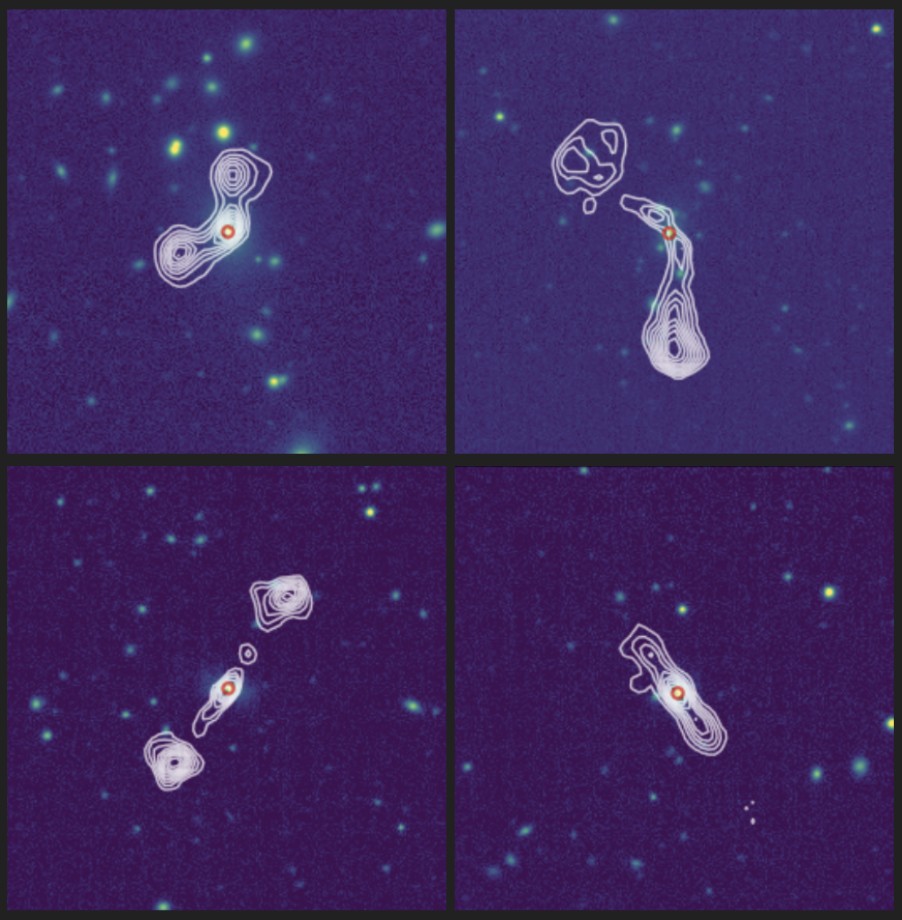

Speed and dense gas bend jets of matter streaming away from some galaxy centers

Paired jets of matter streaming away from supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies usually extend away in opposite directions along the black hole’s axis of spin — as in the two bottom galaxy images. But some, like the two top galaxies, have jets bent at odd angles. Image by Melissa Morris, UW–Madison

The most active and gluttonous black holes in the universe can often be found with two jets of matter streaming from their centers. These jets accelerate with astounding speed out into space in opposite directions, and they are usually lined up along the axis of the spinning black hole. But not always.

Some of these supermassive black galaxy hearts, called active galactic nuclei, have jets bent at mysteriously odd angles. New research from astronomers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, published recently in The Astronomical Journal, shows that these jets are probably bent by a combination of their galaxies moving at tremendous velocity and by drag on the jets as they pass through clouds of intergalactic gas.

Melissa Morris

“These active galactic nuclei are a subset of black holes that are — even for black holes — really quickly gobbling up an enormous amount of matter,” says Melissa Morris, a UW–Madison astronomy graduate student and lead author of the new study. “They’re being fueled so quickly that a ton of energy is released in the area around the black hole. That’s what causes these wild AGN jets.”

Understanding the environment that shapes jet direction helps astronomers understand how galaxies evolve, but just how the matter is launched away from a black hole is an open question. Supermassive black holes are found at the center of almost all large galaxies.

But how ever jets are formed, astronomers find them useful. Incredibly hot plasma in the jets produce radio waves that astronomers can observe reaching far outside their galaxies, pointing back towards the centers of galaxies that produce them like helpful arrows on an otherwise empty map.

“It’s not always easy to see things in space. Sometimes you have to get creative,” Morris says. “The fact that we can ‘see’ these jets — we can pick up the radio waves they make — means that we can also see them interacting with stuff that exists outside of the galaxy.”

This makes the cause of bent jets particularly interesting, and why the UW–Madison researchers — including astronomy professors Eric Wilcots and Sebastian Heinz and staff scientist Eric Hooper — set out to find whether something about galaxies’ surroundings are pushing the jets askew.

“The fact that we can see them bending probably means we can infer something about their environment,” Morris says. “But can we be sure of that?”

Using expansive 3D maps of the universe, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the FIRST Radio Survey, Morris collected a list of 160 galaxies with strong radio-emitting jets that are also bent,. From other star catalogues, she built a pool of galaxies with unbent jets for comparison.

For each galaxy, the astronomers used a technique called a friends-of-friends algorithm to identify every neighboring galaxy within a certain search radius, and then every neighbor of each of those galaxies within the radius, repeating the hunt until there were no more neighbors in the chain.

A cluster of galaxies gathered in close proximity is more likely to be thick with gas and dust, the sort of dense environment that astronomers expected could push an AGN jet slightly off-axis. Sure enough, the AGNs with unbent jets were more likely to be found alone or paired with just one other galaxy. AGNs with bent jets were more likely to be found comingled with groups of three or more galaxies.

An AGN zooming through space at high speed is also likely to have jets that appear bent, as the ends stream out and appear to trail behind the moving galaxy core. So, the astronomers also compared the relative brightness of the galaxies they studied. Brighter galaxies are typically more massive. The biggest galaxy among a cluster is the anchor of the group, sitting at the center of the cluster members’ interactions. Dimmer, lighter galaxies would be getting pulled more rapidly through their neighborhood.

“The brightest galaxy in a cluster is sort of the boss, with the other galaxies in greater motion around it,” Morris says. “And we saw that more than 90 percent of our unbent AGNs in groups were the brightest in the cluster. They are probably not moving fast enough to make their jets appear bent.”

It’s likely a combination of surrounding space heavy with gas and high speed that puts a kink in an AGN’s jets.

“It’s a balancing act,” says Morris. “If you have a super-dense medium to pass through, it wouldn’t take a ton of velocity to make bent jets. And galaxies moving at high velocity wouldn’t need as much gas in the way to have an AGN with a bent jet.”

Researchers continue to tease out the relative influence of different conditions.

“We don’t get to watch a single galaxy change over time. That take billions and billions of years,” Morris says. “So, the better we can determine what has caused certain types of galaxies to look different from others, the better we can understand how they evolve and interact.”

Tags: research, space & astronomy