Research effort driving advances to combat traumatic brain injuries

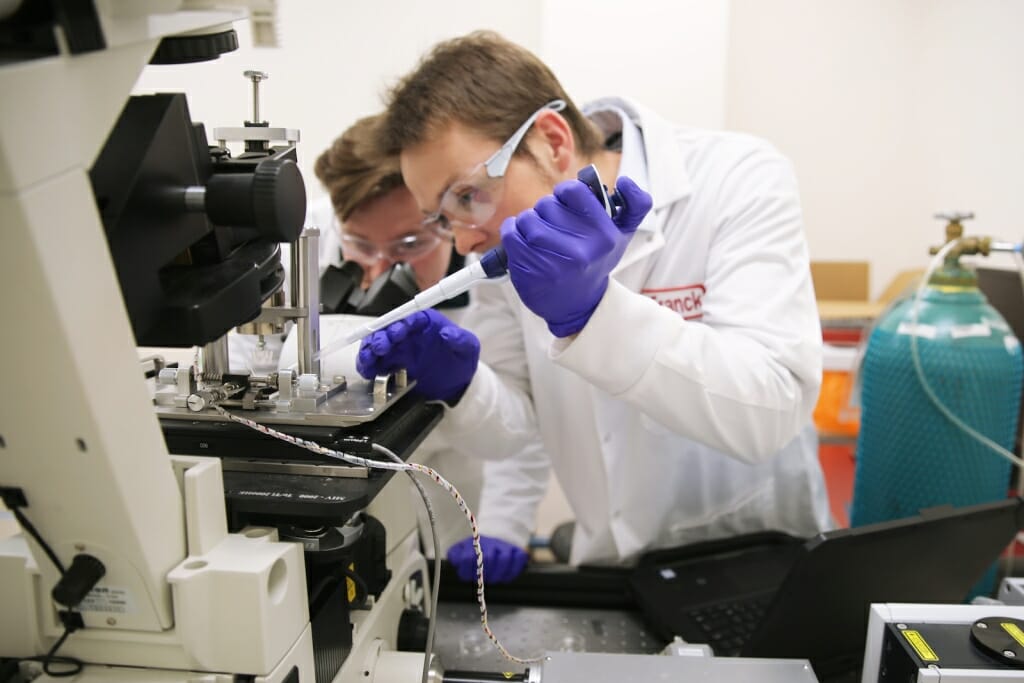

Mechanical engineering professor Christian Franck — at right, in this photo taken before the COVID-19 pandemic — and graduate student Harry Cramer prepare to deliver an impact to a network of cells in a dish, simulating the damage of a concussion-causing collision. Photo by Kristen Koenig

Many concussions don’t produce noticeable symptoms, leaving them likely to go undiagnosed and putting the injured at increased risk for lasting complications like brain damage.

A team of researchers led by University of Wisconsin–Madison mechanical engineer Christian Franck is working on better ways to detect concussions and better protective equipment to prevent them.

Christian Franck

Called PANTHER, the group of scientists from academia, industry and federal agencies has a new $10 million grant from the U.S. Office of Naval Research backing their research.

“In order to design better helmets and new technologies for mitigating traumatic brain injuries, we first need a better understanding of how these injuries originate in the brain cells,” Franck says. “This is a key research area that we’re addressing with the PANTHER program.”

In his own research, Franck is working to quantify the exact amount of mechanical stress and strain that it takes to damage brain cells enough to cause a concussion. He and his colleagues will use that cellular injury data to develop high-fidelity computational models of the human head and brain.

“These sophisticated models will be like an anatomically realistic ‘virtual head,’” he says.

The researchers will subject that virtual head to a range of forceful impacts from a variety of directions and compute the resulting stress and strain in the brain tissue. Franck says those results will help reveal what types of impacts and head motions are most harmful for the brain, as well as allow the researchers to make predictions about concussion risk.

The team is also developing tiny sensors to fit inside helmets and provide real-time impact monitoring as people engage in activities ranging from military training exercises to sports practices. By integrating data from those sensors into their computer models, the researchers will be able to make injury predictions that are directly linked to real-world events.

For example, data from a helmet-to-helmet collision on a football field could be transmitted by sensors inside the players’ helmets, analyzed by the researchers’ models and accessed immediately by a doctor.

“The physician would receive a graphical readout of the player’s head, and it would say something like, ‘Based on the collision that just happened, there is an 80 percent chance of having severe damage in the hippocampus,’” Franck says.

The new funding also will allow PANTHER researchers to expand the scope of their work to include blast-induced concussions, a significant concern to the military.

In addition, the team is pursuing a new approach to aid in the development of reliable blood or saliva tests for diagnosing concussions. During a concussion, brain cells release proteins as a stress response. By studying injured brain tissue, the researchers will work to identify specific proteins or other biomarkers that may be promising targets for future diagnostic tests.

Franck says the new funding will allow PANTHER to rapidly translate its scientific discoveries into products and public health information that will help reduce traumatic brain injuries.

“Although this research effort is motivated by the U.S. Department of Defense’s goal of reducing traumatic brain injuries suffered by members of the military, the basic scientific advances that we make will also benefit the public broadly,” Franck says. “With PANTHER, we ultimately want to solve the brain injury problem in society as a whole.”

Partners in PANTHER include researchers from Brown University, Robert Morris University, Colorado School of Mines, the University of Texas, Arlington, the University of Southern California, Iowa State University, Johns Hopkins University, and Sandia National Laboratories. Industry partners include Trek Bicycle, Milwaukee Tool and Team Wendy, which develops protective equipment.