Renewed partnership keeps $60 million satellite center in Madison

It was a deep history in satellite meteorology that first got the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration interested in Madison in the 1970s.

When it came time to decide anew where best to put the $60 million and 130 people keeping us eyeball-deep in satellite data on Earth’s climate, three more decades of success didn’t exactly work against UW–Madison.

UW-Madison meteorologist Verner Suomi (left) inspects an early satellite instrument in this photo taken in 1959. Suomi’s designs — and the work of the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies, which he brought to UW–Madison — broke ground for an era of satellite-assisted climate studies that now influence everything from global climate models to the weather maps on the nightly news.

Photo: courtesy UW Archives

“The field of satellite meteorology was founded here on UW–Madison’s campus,” said Steve Ackerman, director of the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies and professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences. “We’ve been experts for 30 years and that expertise remains here.”

NOAA recently announced that CIMSS — formed in Madison in 1980 as a joint venture between the federal agency and the university’s Space Science and Engineering Center, would stay put for at least five more years.

It’s the first open competition since the founding of CIMSS, and comes with up to $60 million in funding aimed at further refining satellite technology and use of data collected from space. The agreement allows for a review in 2015 that could add another five years.

Decades of cooperation make for a research partnership of unique depth, according to Jeff Key, chief of NOAA’s Advanced Satellite Products Branch and head of the agency’s seven-member contingent at CIMSS.

“The expertise at CIMSS in Madison is broad and covers a wide range of activities from basic satellite algorithm development to operational implementation of satellite products,” Key said. “That end-to-end spectrum of activities is very important to NOAA and very hard to duplicate anywhere else.”

Ackerman

Unique work started at UW–Madison in the 1960s with Verner Suomi and Robert Parent, a meteorologist and an engineer with the idea that satellites like the recently-launched Sputnik could be used to measure the ebb and flow of heat between the Earth and space.

Suomi made Madison the cradle of satellite meteorology by developing the core technology — a camera capable of holding its focus on one piece of Earth, and a sensor that records temperature and moisture data for the ground and cloud-tops — for the line of Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites.

Not content simply to gather the data, Suomi also developed the Man-computer Interactive Data Access System, which translated weather information into computer graphics for forecasting and reporting.

GOES and McIDAS remain workhorses among NOAA’s alphabet soup of a forecasting and research tools and a focus for students, faculty and NOAA scientists.

The fifteenth GOES satellite was launched in March, but CIMSS scientists have already booked years of work in on the seventeenth spacecraft in the series (scheduled to be lofted into orbit in 2015 and look back on the planet through 2027).

Video: Research Profiles—CIMSS

“We work with NOAA to develop appropriate uses for the data the new GOES will collect,” Ackerman said. “We set up an atmospheric condition, simulate what the new satellite should see to make sure everyone is getting every bit of usefulness out of the data when it starts coming in.”

That data-wringing goes back to Bill Smith, CIMSS’ first director, who figured out how to “sound” the sky like the ocean, taking temperature and moisture measurements at a series of altitudes down through the atmosphere to the ground.

Among the institute’s contributions over the last 30 years are methods for detecting fires and measuring wind speeds from space.

“To find the wind, we follow the clouds,” Ackerman said. “I know that sounds easy, but believe me, it’s tricky.”

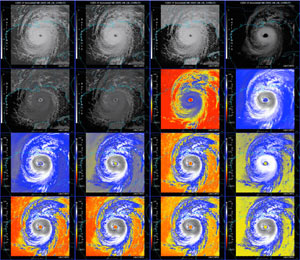

In a project called the GOES-R Proving Ground, scientists from the UW–Madison Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies prepare the software that will provide weather forecasters and atmospheric researchers with data from new meteorology satellites. Here, component parts of hurricane Katrina are viewed via several simulated data streams for the GOES-R satellite, scheduled for launched into orbit in 2015. Only five of these data streams are available from the active GOES-12 satellite.

Photo: courtesy CIMSS

The institute’s work has played directly into improved understanding of Earth’s complicated climate and weather forecasting, including warnings of oncoming severe storms. From hailstorms to hurricanes to airline-confounding volcanoes and oil slicks in the sea, CIMSS can put its cameras and computers on almost anything.

“If you’ve see a satellite image on TV or the Internet or in the newspaper or anywhere, CIMSS has played a role in it at some point in history,” Ackerman said. “Renewing the partnership with NOAA offers us an opportunity to sit back and do some strategic planning about the organization. Where are we now and where are we going? The challenge becomes how do we transition from those accomplishments to the new goals we have for satellites — like monitoring the effects of climate change.”

That includes development of the latest GOES satellite and the new Joint Polar Satellite System, which will speed the delivery of weather information and add to long-term climate observations.

Key expects UW–Madison will handle the next decade of CIMSS in stride.

“There’s very strong science here at CIMSS, and all the computing and software that goes along with it is a strength of the university,” Key said. “We’re really happy CIMSS won, and that we’ll be collaborating for another 10 years.”