Preserving art: Why Notre Dame Cathedral – and art – matter

Professor Anna Andrzejewski talks with students during an art history course. Photo: Bryce Richter

Anna V. Andrzejewski had just finished teaching History of American Art and Architecture Monday. The class was talking about revival styles in late 19th-century architecture and the “Gothic Revival.” After class, the UW–Madison art history professor heard the news – Notre Dame Cathedral was on fire.

How bad was it? Was anyone hurt? Was this real? Andrzejewski had a lot of the same questions others did, but as an art historian, she has another perspective. Her interest in art was inspired by a humanities class in high school taught by a retired college professor of art history.

“He convinced me places like Notre Dame mattered,” she says.

But why? To some, the answer is obvious. Andrzejewski offers her thoughts about what makes Notre Dame so significant and why preserving art is important.

Her family visited Notre Dame Cathedral in August 2017. Her daughter, then 14, had studied French in middle and high school and had begged to go to Paris.

“We all saved our money for a few years – my daughter saved portions of her allowance and dog walking money – so we could go,” Andrzejewski says.

Their first tourist destination was to Notre Dame – it was her daughter’s first choice.

For those of us who haven’t been to the Notre Dame Cathedral, can you describe what makes it so special?

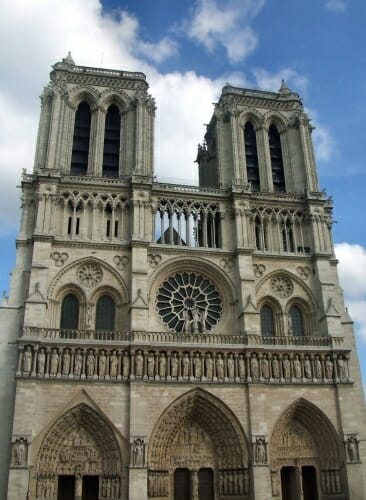

Notre Dame is special not simply as one of the grandest Gothic cathedrals (in France and in Europe generally) – which it certainly is – but because of its special relationship with French identity. It has become in many ways a symbol of France and the wonder that is its capital city of Paris.

Being in the Cathedral is awe-inspiring in two ways: the scale and the light from the stained-glass windows. Its scale is mystical, which is precisely the point its builders and the Church wanted to convey.

It was a special structure, celebrating Christianity, and it housed relics associated with saints (and Jesus – the crown of thorns he supposedly wore). So they used the vaults to build it “toward heaven.” It’s also a cross-plan, symbolic of its function, which was common for these structures, but the vaulting is so grand and the scale so amazing, one really just has a feeling of wonder (and the cross plan doesn’t seem that significant as the eye is drawn upwards). The stained-glass effects add to this ethereal experience. We were there on a sunny day and the colors were brilliant in the windows and in the church itself, which was filled with an almost mystical light.

As an art historian, can you help put this into perspective about why it is so important?

I feel buildings like Notre Dame are important for multiple reasons (and not simply because they are “old”). First, and perhaps most obvious, they are wonders of construction. The builders who constructed cathedrals during the Medieval period were master craftsmen, no doubt, but how they built on the scale that they did without modern tools is still awe-inspiring. They were able to adapt earlier building technologies pioneered by ancient Greeks and Romans and in many ways go beyond their achievements.

Medieval builders perfected the use of vaulting and the use of flying buttresses, which enabled them to build to great heights. They didn’t have trucks to transport the stone or cranes to hoist materials. And that’s just the building itself; think of the craftsmanship that went into the stained-glass windows! Losing these buildings is to lose touch with craftsmanship, and the fact the roof of Notre Dame was lost in the fire means we’ve lost tangible evidence of Medieval building technology.

Second, these buildings provide us with access to the past in a visceral way. In my field, architectural history and material culture, we often say that buildings and objects are the only form of history that survives to the present. That’s important, because these things tell us about what builders and users valued in the past. In this case, the towering, wondrous buildings like Notre Dame tell us about Medieval priorities, namely the Christian religion. This was the age of the crusades, and glorifying God was clearly important to them to devote resources to cathedrals on the scale of Notre Dame.

Finally, these buildings are important because of associations we have with them. All the Facebook pictures of people in front of Notre Dame enshrines the building with personal memories; that’s not insignificant. But in the case of this building, it really is a symbol of France, and of Paris, in particular. It’s been added onto and rebuilt before because it’s a symbol of French national pride. Buildings matter in this way – to individual people and to cultures of which they are part.

It’s not just the pieces inside but the architecture itself. What makes it so distinctive?

As an architectural historian, I know less about the art inside (most of which was rescued from the fire) than the architecture. When you ask what’s distinctive, it’s sort of interesting, since the way I teach this building is as a “typical” Gothic cathedral (as if such a thing exists!). But it does have features – the cross plan, the valued nave and side aisle), abundant stained glass – that lends comparison with other French cathedrals, such as Chartres. If I was to say what’s distinctive, there is artwork that is unique – much of which was saved – and of course, the relics inside.

Technology may play a role in rebuilding. Years ago, a Vassar College professor used cutting-edge laser scanners to capture over a billion points of data that can be used to create a 3-D model of the cathedral. How else is technology useful when it comes to preserving art?

One of the reasons I participate in historic preservation is for its documentary function. For nearly 100 years now, the Historic American Buildings Survey of the National Park Service has prioritized documentation of historic American buildings through measured drawings and photography. For historically significant buildings, thorough recording of the plan, elevation, section, and details (i.e., framing plans) preserves a record of them in case of demolition or tragedy.

It’s not the same of course, to having the actual building, but it is something. New digital technologies are coming in to supplement and in some cases replace hand drawing, which makes this process (in some ways) easier. Still, documenting a building is never a substitute for the building itself. For example, drawing (especially digital AutoCAD) has a tendency to regularize things that aren’t regular in a historic building, and rebuilding a structure with new materials isn’t the same; it just isn’t. But these documentation processes are important nonetheless as tools to help preserve aspects of past buildings when they are lost.

While technology may help us tour museums throughout the world from the comfort of our computer, what is it about seeing art in person that makes the experience so different?

I always tell my students that “the real thing” produces an entirely different experience – and nowhere is this truer than with buildings, because we, as human animals, move through space and it’s how we relate to buildings. With Notre Dame, pictures capture parts of its glory – but you can’t “see” or “feel” what the experience of it is like as one could have in the Medieval period. You might have a picture of the stained glass, but relating that window to the nave, or the building as a whole, can’t happen without being there. And virtual reality is just what it says it is: virtual. It’s a partial replication of the real, not the real itself. It has none of the sense of age or “weathering” one sees at Notre Dame, for example; it’s an abstraction in a way.

I recently visited the Florence cathedral, and toured the inside of the massive cupola dome there. Inside was tons of graffiti – some dating back centuries. You’re not going to capture that in a digital scan, and yet the fact people have done that for centuries is interesting to me, and part of the building now (and thus part of the experience).

Art is often considered a luxury — something that is non-essential. As millions of dollars of donations pour in, many are wondering how else that money could be used. What are your thoughts?

This is a fair point, but I am not one to judge value of “causes.” But I think it’s important people have choices about what to do with their income (and are exercising it to try to rebuild parts of Notre Dame). I’m glad the fire at Notre Dame has prompted conversations about funds for other historic buildings, including historic sites destroyed by ISIS, for example. The point is buildings are much more than functional structures; they have meaning to people and communities, in the sense they have symbolic value as monuments. This is true for Notre Dame, but it’s true for buildings all across the world (the product of many cultures), and I think just as this building has been deemed important by philanthropists willing to pour money into restoration, other buildings elsewhere – religious structures important to other faiths and nations, for example – deserve equal attention.

I will say this: that the cost of restoration and rehabilitation is far cheaper than of reconstruction in the case of catastrophic loss. What I mean by this is “preservation” is cheaper than rebuilding. Of course, this is what they were intending to do at Notre Dame, and then disaster struck; but now it will be more expensive. If we place a value on buildings, I would like to see philanthropy directed into preventing disasters – including recording buildings – rather than being only reactive (and coming in after it’s too late).