Pioneer of climatology dies at 88

Reid Bryson, a towering figure in climatology and interdisciplinary studies of climate, people and the environment, and the founder of the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s meteorology department and Center for Climatic Research, and the first director of the Institute for Environmental Studies, died in his sleep early June 11 at his home in Madison. He was 88.

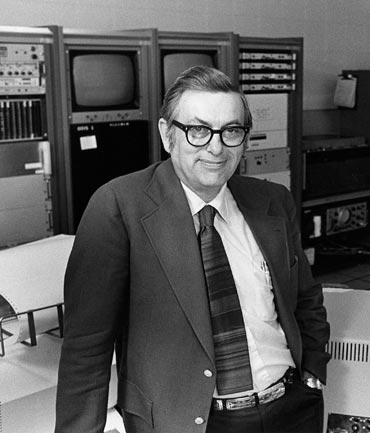

Pictured here in a 1981 file photo, Reid Bryson is a founding figure of modern climatology. Bryson pioneered the use of computer models in climate science and was a master integrator of diverse fields of knowledge long before interdisciplinary research became a trend. He founded UW–Madison’s meteorology department in 1948 and, in 1970, helped establish what is now known as the Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. Bryson passed away on June 11, 2008.

Photo: UW Archives

Bryson was one of the pioneers of modern climatology and was among the first to explore the influence of climate on humans and human culture and, in turn, some of the human impacts on climate. He was an early developer of simple computer models to study the causes of past climate change, comparing those simulations with records of paleoclimate and human culture.

He gained fame for his theories of past and future climate, and for his studies of the relationships between climate and the biosphere as well as climate and human societies.

A polymath, Bryson’s scholarly interests ranged from studies of archaeology and geography to geology and limnology, and he tied them together through an abiding interest in weather and climate. His first appointment at the University of Wisconsin in 1946 was in geology. In 1948, he founded the university’s meteorology department, now known as the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, and was its first faculty member and chair. In collaboration with the late Verner Suomi, another pioneering Wisconsin meteorologist and the father of weather satellites, Bryson made the department one of the largest and most prestigious in the country.

An innovative researcher and influential teacher, Bryson excelled at work in the field, studying climate on every continent, and was especially interested in the influence of climate on human history and culture. In his retirement, he traveled the famed Silk Road to sate his many interests in history, human cultures and places.

Bryson was prescient in grasping the depth and breadth of the many connections between climate, the environment and human society, according to John Kutzbach, UW–Madison professor emeritus of atmospheric and oceanic sciences and one of Bryson’s students. "His interdisciplinary interests and knowledge of these topics allowed him to see connections that others missed and to initiate studies that are still at the cutting edge of climate research."

"Reid was a different kind of scientist. He excelled in the field as well as in the lab with computers," says Jonathan Foley, a UW–Madison climate scientist himself trained by one of Bryson’s students. "He had a real world grasp of the influence of climate on people. No one came close to his breadth of understanding."

Reid Allen Bryson was born in Detroit on June 7, 1920. He earned a bachelor’s degree in geology from Denison University in 1941 and his doctorate in meteorology from the University of Chicago in 1948, the same year he founded the University of Wisconsin’s meteorology department.

During World War II, Bryson was a major in the Weather Service of the U.S. Army Air Corps, making forecasts from Guam for the B-29 air crews on the first high-altitude bombing missions over Tokyo. Forecasting the weather at 30,000 to 35,000 feet, an altitude where few aviators had been before, Bryson and colleague William Plumley calculated 168-knot winds over Tokyo, a "fantastic forecast" disbelieved by the commanding general. Their forecast was correct, the mission failed and the commanding officer apologized. The high-altitude winds measured by Bryson and Plumley later came to be known as the jet stream.

At Wisconsin, Bryson, who was also a published poet and a weaver, indulged his many scholarly interests and in doing so forged a model of interdisciplinary research that was decades ahead of a trend now firmly established in higher education.

"Now, interdisciplinary studies is almost like a mantra," explains Jonathan Martin, the current chair of the department Bryson founded. "Reid Bryson was almost 40 years ahead of the curve. It came organically, out of his own curiosity and many interests."

At the time, however, Bryson lamented the fate of "integrators" in academia. He told the New York Times in a 1989 interview: "You’ll never get a Nobel Prize, for example. For that you’ve got to be in a single discipline."

The UW–Madison Center for Climatic Research was founded by Bryson in 1963. He analyzed ancient tree rings to deduce past climate and studied fossil pollen to learn that arid parts of India were once much wetter environments. He went on to devise a system of land use to help reduce the overgrazing that had made the Indian landscape drier.

"Through field studies and travels to all the continents, he developed a unique understanding of the relationship between ‘climata’ and ‘biota’ — the complex array of variables that link the diverse climates of the planet to its equally diverse ecosystems," according to Kutzbach.

In 1970, Bryson was instrumental in establishing the UW–Madison Institute for Environmental Studies, now known as the Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. He was its first director, serving from 1970-85. The institute continues to exemplify the interdisciplinary approach to science instilled by Bryson, says its interim director, Lewis Gilbert.

While at the institute, Bryson helped put in place the curriculum for undergraduate courses in environmental studies as well as programs for graduate studies in climate, water and land resources.

A thoughtful critic of the use of complex computer models to estimate future climate, Bryson himself employed their early use in climate science. He used his models to isolate single factors — volcanic eruptions, the slow wobble of the Earth on its axis — to see if and how they influenced past climates, and how climate might act in the future.

"He was a masterful synthesizer and communicator of information," recalls John A. Young, a UW–Madison professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences and a Bryson colleague. "He very effectively took climatologic knowledge and applied it to human history. He was a Renaissance man of our science. He was unique."

Bryson is survived by his wife, Francis, of Madison, and four children.