NOAA plan to improve weather forecasting includes UW–Madison

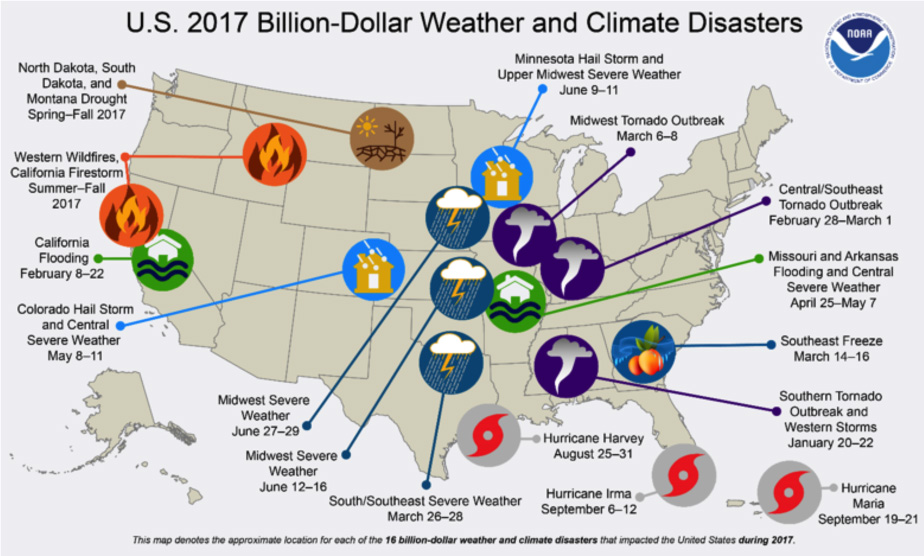

This map depicts the general location of the 16 weather and climate disasters assessed to cause at least $1 Billion in direct damages in 2017. Image courtesy of NOAA

Whether deciding to stock up on nonperishables or assessing energy needs ahead of a winter storm, weather is a billion-dollar industry that touches everyone — individuals and industry alike.

This is among the reasons Neil Jacobs, assistant secretary of commerce for environmental observation and prediction at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), visited Madison for a listening session on Nov. 26. He was gathering input and laying out a vision to improve U.S. weather forecasts to better meet the needs of society.

Neil Jacobs, assistant secretary of commerce for environmental observation and prediction at NOAA. Photo by Bill Bellon, SSEC

Jacobs’ visit emphasized the role of the NOAA cooperative institutes, like the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS), in mitigating weather-related losses by increasing innovation and research opportunities.

“Severe weather impacts roughly 3 to 6 percent of GDP annually (gross domestic product),” Jacobs said at the event.

According to the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Prediction, from 1980 to October 2018, the U.S. experienced 238 events that exceeded $1.5 trillion in losses. In 2017 alone, the U.S. experienced 16 historic weather events, each exceeding $1 billion in direct losses.

“These numbers are derived from losses of insured assets,” said Jacobs in a later interview, “but I have a feeling the number would be much larger if indirect impacts were factored into the equation, like delays in transportation, increased energy costs, or lost tourism revenue.”

Industries, he said, are starting to incorporate forecast products into their planning. For example, stores may stock up on generators before a hurricane makes landfall, or on snow shovels ahead of a winter storm. These are the types of decisions that can improve public safety and business operations, which is why Jacobs continues to meet with private sector, industry and academic partners around the country.

Jacobs is working with each cooperative institute as their strengths dictate, but improving forecasts is the top priority, he said, and CIMSS is “at the top in this area,” due to its expertise in satellite data assimilation.

For example, CIMSS scientists are incorporating satellite observations into numerical weather models to improve hurricane forecasts. Using a supercomputer housed on-site as part of a collaboration between UW–Madison and NOAA, they are also testing the forecast accuracy of a model that is a component of a new global prediction system.

The European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts has developed a high performing global model and the U.S. is striving to improve. Having university expertise working on innovative solutions to formatting satellite data and informing NOAA strategy is important to this goal.

Jacobs sees cooperative institutes like CIMSS as testbeds for this type of research and development. And CIMSS is no stranger to innovation.

In fact, the memorandum of understanding between UW–Madison and NOAA that created CIMSS emerged out of a skunkworks arrangement that brought federal scientists to Madison to work alongside university researchers to experiment with and solve forecasting problems. The partnership has proven successful for nearly four decades.

Jacobs envisions a return to this type of experimentation at the cooperative institutes and noted that other agencies, such as NASA and the Department of Defense, are already using this type of architecture to great advantage.

Jacobs noted that NOAA is also looking to improve the ways institutes cooperate with each other and with the federal government by erasing artificial barriers between them.

For example, a nonfederal entity like the UCAR (University Corporation for Atmospheric Research) Community Center in Boulder, Colorado, could offer a cloud-based testbed where the cooperative institutes can conduct NOAA-funded research and testing.

Jacobs hopes that creating a unified and transparent computing environment will help improve NOAA’s approach to resource allocation and have the added benefit of bringing together researchers who may be working on similar problems.

“NOAA wants to be open to all innovation — from the cooperative institutes to industry,” Jacobs said. “We do not want to restrict what may be a novel idea; if it works for our public service mission, then we will consider it.”

Tags: meteorology, research, weather