New book by UW lecturer examines legacy of activist incident

Growing up in Catonsville, Md., a suburb of Baltimore, Shawn Peters can’t remember the first time he heard about the Catonsville Nine. He was 18 months old in May 1968, when nine people — including two brothers, both well-known activists and Catholic priests, and a former nun — removed hundreds of files from the local draft office and burned them with homemade napalm.

Peters heard a variety of stories about the incident: some straightforward accounts, others more fanciful, told by people who claimed to have been somehow involved. A popular play, and later a movie made by Gregory Peck, was created from more than 1,000 pages of court transcripts, shaping the historical memory of a generation.

But Peters also saw the ambiguity — in both the causes and the effects — of these actions.

“I’ve known since I was 15 years old that I wanted to write a book about this,” says Peters, now an instructor in the Integrated Liberal Studies (ILS) program and coordinator of teaching and learning for the Center for Educational Opportunity (CEO) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “To me, it was an interesting story because it was kind of confusing and contradictory.”

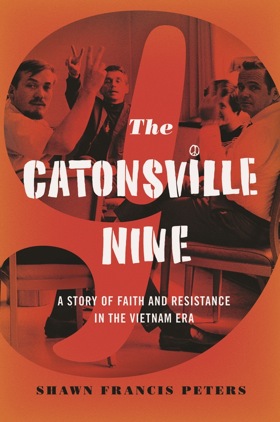

Peters’ new book, “The Catonsville Nine: A Story of Faith and Resistance in the Vietnam Era,” published by Oxford University Press, provides a more complete picture of this incident than had previously existed. Even now, the participants continue to be both celebrated and reviled, but Peters says he hopes to move away from the idea of “heroes and villains.” Showing the complexity of the participants’ lives and motives, he also examines the equally valuable perspectives of their critics, both at the time of the incident and during the following decades.

Creating a group biography proved a considerable challenge. The smaller stories woven into the lives of each participant add to a compelling narrative arc. Peters arranges the story with architectural precision, eschewing linearity to give each building block its own space.

Many previous works focused on the iconic Berrigan brothers, the most well known of the group before and after the incident. The brothers had actually joined late in the planning, taking the spotlight from some of the original organizers.

“I enjoyed writing about all of the [Catonsville] Nine, but especially two of them: David Darst and Mary Moylan,” Peters says. “They had tragic stories, ultimately, and I made it my mission to tell those comprehensively in a way that hadn’t often been done. The more I got into those stories, the more I realized that they stood up on their own.”

Though the Catonsville Nine are commonly considered anti-Vietnam protesters, their agenda went much further. Exploring the lives of the other seven protesters allowed Peters to demonstrate the ways in which they hoped to make a global impact.

Several considered Vietnam an example of sickness in the global body politic. Marjorie and Thomas Melville, both members of Catholic religious orders before marrying, had recently been expelled from Guatemala for involvement in that country’s “internal politics”- including organizing university students on labor and literacy issues.

“They saw themselves as part of a wider cause: targeting the war, inequality, poverty,” Peters says. “They certainly didn’t believe that attacking one draft board and destroying 300 files would end the war, but they thought that they could inspire others to do acts of creative nonviolence.”

Forty-four years later, the Catonsville Nine’s actions — and other Vietnam-era incidents — still provoke strong feelings on all sides. Peters believes that the Nine acted on the basis of noble motives, but didn’t necessarily understand how their actions would be received and contextualized by others. But he also believes that their stories provide a good example of the perils of righteousness.

“Our current political environment is increasingly polarized,” he says. “Being able to step back from your own sense of right and wrong, evaluate and process rhetoric, and try to make meaning of other people’s perspectives is something that we seem to do less and less.”