Marine Protected Area creates spillover benefits for tuna fishing in Hawaii

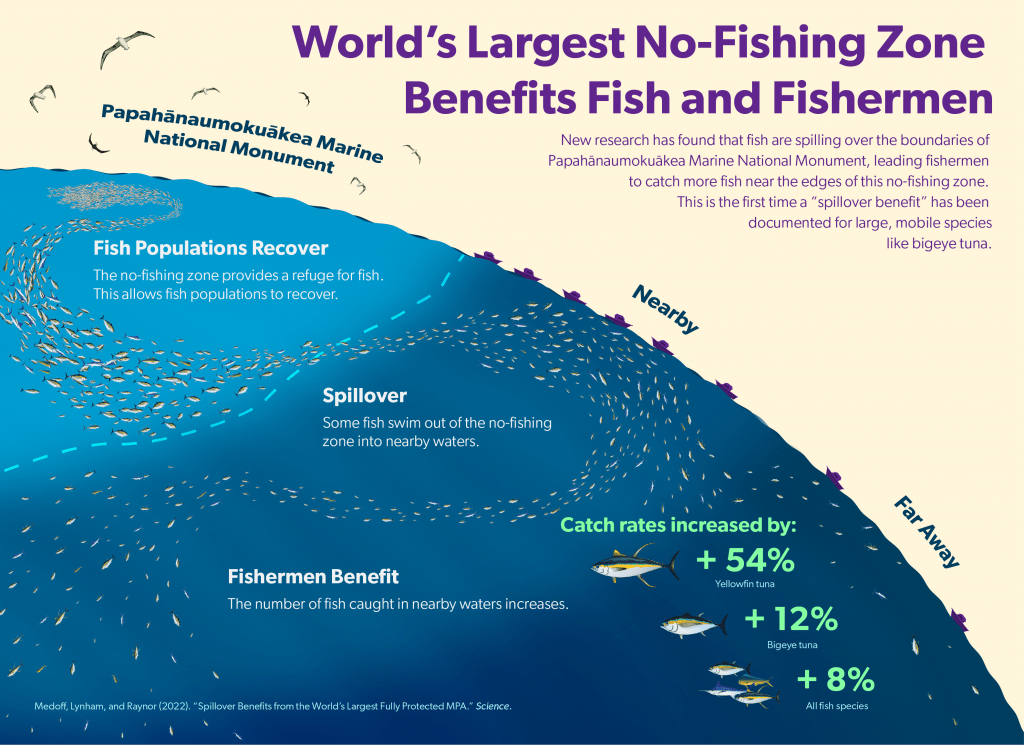

Graphic demonstrates spillover benefits from the world’s largest no-fishing zone, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Data: Medoff, Lynham, and Raynor (2022). Graphic by Ben McLauchlin at benndiagram.com

A new study shows that carefully placed no-fishing zones can provide benefits for both fishermen and fish populations.

Jennifer Raynor, a professor of natural resource economics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, collaborated with researchers from the University of Hawaii to study how the creation of the world’s largest marine protected area (MPA) in Hawaiian waters affected the local tuna fishing industry. The study was published recently in the journal Science.

Jennifer Raynor

In 2006, the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument was established to preserve important cultural sites for Native Hawaiians; the protected area was expanded to about four times its original size in 2016. The monument was a major victory for conservationists but raised concerns among local fishermen about losing access to these fishing grounds.

“The intention for creating this space was not necessarily to protect tuna. The fact that it did was in some ways a happy accident,” Raynor says.

There are both cultural and economic factors wrapped up in the monument and the tuna fishing industry in Hawaii. Tuna is a central part of Hawaiian diet and culture; protecting Hawaiian cultural sites is central to the MPA. But tuna fishing also generates $40 billion a year to the global economy and supports millions of jobs.

In some ways, Raynor says establishing these no-fishing zones with a cultural motivation rather than a scientific motivation of protecting tuna populations makes it more difficult to justify the MPA to fishermen. That’s why it was important to show through this study that despite the upfront costs, fishermen are already starting to benefit from the MPA, and those benefits are expected to grow in the future.

What makes this MPA a win-win-win for the environment, native people and fishermen is a concept called “spillover.” The idea is that protected waters give the species a chance to flourish, causing an increase in overall population that can spill over beyond the MPA and increase fishermen’s catch rates and profits.

“I am a big fan of evidence-based policy,” Raynor says. “I think the best way we can make good policies that are efficient, effective and sustainable is to understand the science that tells us what direction we should be going in.”

Tuna for sale at the Honolulu Fish Auction in Hawaii. Photo by Sarah Medoff

To show that the MPA actually caused the increased tuna populations, Raynor played a key role in applying a statistical technique referred to as “difference in difference.” This technique compares catch rates for fish near the monument to areas farther away, both before and after the monument expansion in 2016.

The results showed that catch rates in waters close to the MPA increased by about 54% for yellowfin tuna, about 12% for bigeye tuna and about 8% across all fish species.

Since many tuna remain within 200-400 miles of the Hawaiian islands during their lifetime, the team also looked at how catch rates change in 1-mile increments up to 600 miles away from the MPA border. They found that catch rates rose as they grew closer to the monument.

Seeing increases like this in migratory species is significant because similar results had only previously been seen in resident fish populations.

“This is a great thing for Native Hawaiians,” Raynor says. “This protected area that they were fighting so hard for actually creates benefits for ecosystems and benefits for other people in the region too. I think it’s a really wonderful thing.”

Raynor believes the best way to solve challenging, multifaceted issues is to bring together experts who can add a variety of experiences and perspectives to the conversation. This project and partnership with researchers from the University of Hawaii was an example of that belief in action.

Raynor is a newer addition to the College of Agricultural and Life Science’s Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology at UW–Madison, bringing her expertise in the intersection of ecology management and economics to the university this semester. She earned her PhD in agricultural and applied economics at UW–Madison in 2017 before going on to work at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and later at Wesleyan University.

Returning to UW–Madison and its collaborative research environment was an opportunity Raynor knew she couldn’t pass up.

“People from lots of different disciplines are focusing on one thing: natural resource use and management,” she says. “I was really excited about being in an interdisciplinary department with a great group of people who I have a lot of research synergies with.”

Commercial fishing vessels at Honolulu Harbor in Hawaii. Photo by Sarah Medoff