Maps showing potential for soil contamination issued for Wisconsin’s lead-zinc mining district

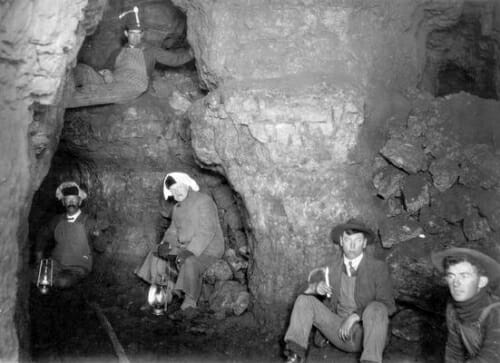

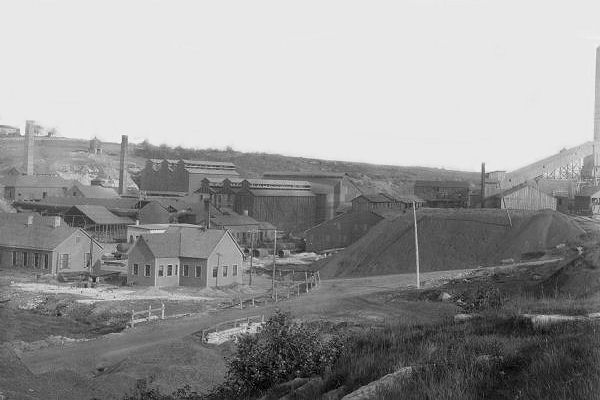

A lead and zinc mine near Dodgeville, Wisconsin, in 1945, long after Wisconsin’s lead and zinc mines outgrew “pick and shovel” scale. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society

Maps showing the aftermath of lead and zinc mining in Southwest Wisconsin became available in early October. The maps build on digitized information about mine shafts, open-pit mines, smelters, abandoned rail lines and other features from the 150-year history of mining for lead and zinc in Green, Lafayette, Grant and Iowa counties.

The digitized Digital Atlas of Historic Mining Features in Southwestern Wisconsin, developed in the department of soil science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, shows areas where contamination may be found. It does not show the results of any soil tests for lead or zinc.

The state mascot memorializes badgers, as the lead miners who started in the 1820s were called. But the aftermath of mining is seldom top-of-mind in the southwestern corner of the badger state.

That ought to change, says Geoffrey Siemering, a researcher in the department of soil science who shepherded the report. “The health effects of lead, especially for children, are largely irreversible. Preventing exposure is the best defense, and although this is not great news for parts of the affected counties, we feel it’s essential to get the information out so people and communities can plan in order to minimize health risks.”

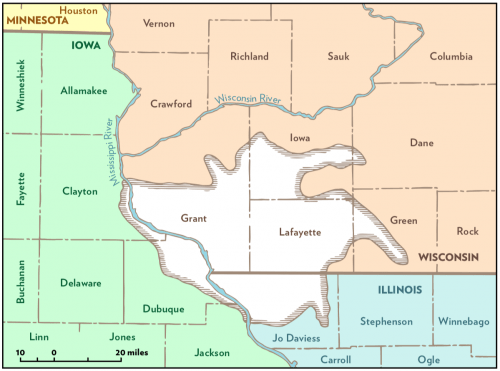

Approximately 4,000 square miles of hilly, unglaciated terrain spanning Illinois, Iowa and Wisconsin make up the historic lead and zinc mining district of the Upper Mississippi River Valley. Digital Atlas of Historic Mining Features in Southwestern Wisconsin

The atlas describes four counties in Wisconsin, and refers to adjacent portions of Iowa and Illinois. Lead mining in this part of the Driftless Area began in the 1820s, and grew quickly. According to the soils department researchers, “from 1830 to 1871, the mining district was by far the most important lead producing area in the United States.”

By the time mining for lead and zinc ceased in 1979, an estimated 600 million tons of ore had been extracted, leaving behind more than 2,000 mining sites.

Lead is highly toxic to the nervous system, kidneys and other systems. So as Milwaukee, Flint, Michigan and other cities grapple with the toxic impact of lead water pipes and lead paint, Doug Soldat, a professor of soil science at UW–Madison, says lead contamination in the soil needs to be considered.

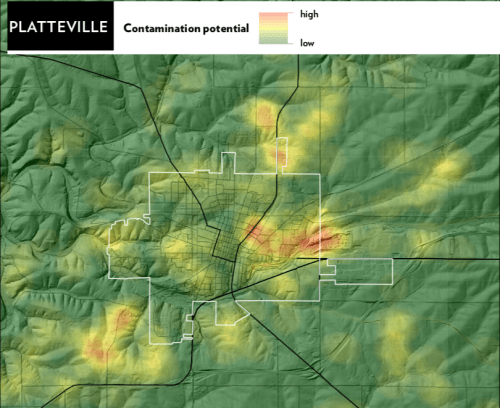

Map show contamination potential in Platteville, Grant County, Wisconsin. Black lines: highways. White lines: City limits. Digital Atlas of Historic Mining Features in Southwestern Wisconsin

The maps are built on mining company records of where lead and zinc were prospected, mined, extracted and smelted. As mines closed, their records were consolidated at the remaining mines. Eventually, six cargo vans hauled records to the Wisconsin Geologic and Natural History Survey, which digitized the Wisconsin portion.

Graduate student Kyle Pepp, working with soils professor Stephen Ventura, processed these records to start the new atlas.

Siemering, an expert in soil contamination, says the maps show an unfortunate overlap of lead and people: Because early settlements revolved around lead mining, people gravitated around lead mines in Potosi, Shullsburg, Platteville and many other population centers.

After the lead or zinc ore was removed from near surface (lead) or deeper underground mines (zinc), it was concentrated by using water to separate the heavier metal-bearing minerals. An estimated 70 percent of the original material removed from the mines was usually dumped in piles near the mine sites. Although not containing enough metal to be worth further processing, this material still contains both lead and zinc at environmentally hazardous levels.

Later rain and runoff carried lead and zinc from tailing sites to local wetlands, streams and rivers. Today, there are six lead- and five zinc-impaired federally listed waterways in this region.

A second source of concern is reuse of mine waste rock, Siemering says. “Photos from the 1920s show huge piles of rock that we don’t see now. Where did they go? No one hauls rock without a purpose and these piles were ready sources of material for roadbeds and foundations.”

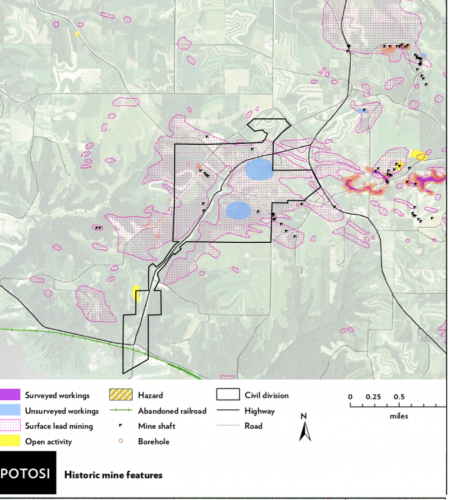

Historic mining features in Potosi, Grant County, Wisconsin. Extensive mining records were compiled into the new digital atlas. Digital Atlas of Historic Mining Features in Southwestern Wisconsin

Because the maps were based on mining records, not on-site measurements, soil tests would be required to determine actual lead levels, Siemering says. In theory, “cleaning up” contaminated soil by removing it or covering it with soil could solve the problem, but hauling contaminated soil to an approved hazardous waste dump can cost $100,000 per acre.

In 1994, an engineer at the Department of Natural Resources estimated that a three-story pile of mine tailings in New Diggings could be cleaned up — for $700,000.

Capping contaminated soil with clean soil may be somewhat less costly, and can work if done correctly, and monitored regularly.

There are other options for reducing human exposure to lead in the soil, says Soldat. “Scientific understanding of the environmental, health and chemical situation can point to lead-abatement tactics that are safer, healthier, and more affordable. So we are focused on finding realistic, affordable ways to reduce the hazard without bankrupting landowners.”

One tactic entails vigilance for signs of contamination. Farmers in Southwest Wisconsin, Siemering says, have noticed yellowed, stunted crops – often a sign of the zinc poisoning. “If you see that, set your tractor GPS to avoid plowing that area and grow a permanent cover like prairie plants to minimize erosion.”

In 2019, Siemering wrote a Division of Extension report on Managing Mine-scarred Lands in Southwestern Wisconsin that provides information for homeowners on the problem and what they can do about it.

In any case, Siemering says, future residential development in the mining district can be focused away from areas that the new map indicates are likely to have high lead soil concentrations.

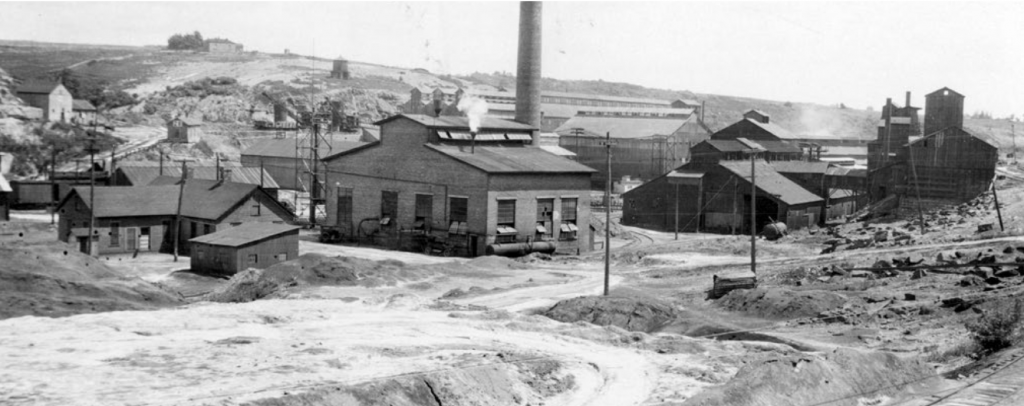

A zinc processing plant in Mineral Point, Wisconsin, in an undated photo. Although zinc is less hazardous than lead, zinc ores contained a substantial amount of lead. Photo by Miningartifacts.org

Badger state history is cast in lead

Lead and Wisconsin were joined at the root: Although explorers and fur trappers were the first European visitors, the first European settlers were largely Welsh immigrants who began the hard, hazardous and toxic underground mining of lead ore in the 1820s.

The first strikes, in Galena, Illinois, were supplanted by richer, more accessible finds across the border in Grant, Iowa and Green Counties.

The Badgers (named for the pits that some lived in) and their occupation did more than nickname the Badger state. In 1836, the legislature of the Wisconsin Territory had its first meeting at Belmont, deep in lead country. And as towns grew up around the mining camps, names like Mineral Point and New Diggings reflected the primacy of mining. (New Diggings referred to Galena, Illinois, AKA “Old Diggings.”)

Tower Hill State Park, near Spring Green, preserves a “shot tower,” a shaft through which workers dropped molten droplets of lead that solidified into balls as they fell. The tower made ammunition from the 1830s until 1860.

Lead from Southwest Wisconsin was likely used in paint, ammunition, batteries, pipes and fungicide. But the lead boom was brief: In 1848 the California Gold Rush siphoned away miners eager to strike the precious metal, and the lead industry was already fading.

In the latter half of the 19th century, the mining focus shifted to zinc, a less toxic metal whose ore also contains leadAs mines “played out,” many were closed or sold to new operators. By the 1960s, the advent of regulations on air and water pollution raised costs and lead to the cessation of metallic mining in southwest Wisconsin by 1979.

But by then, the mining district in Lafayette, Iowa, Green and Grant Counties, together with a spur in western Dane County, produced 600 million tons of ore, which supplied about 2 million tons of metallic lead and zinc.