Here is what you need to know about novel coronavirus, according to a panel of UW–Madison experts

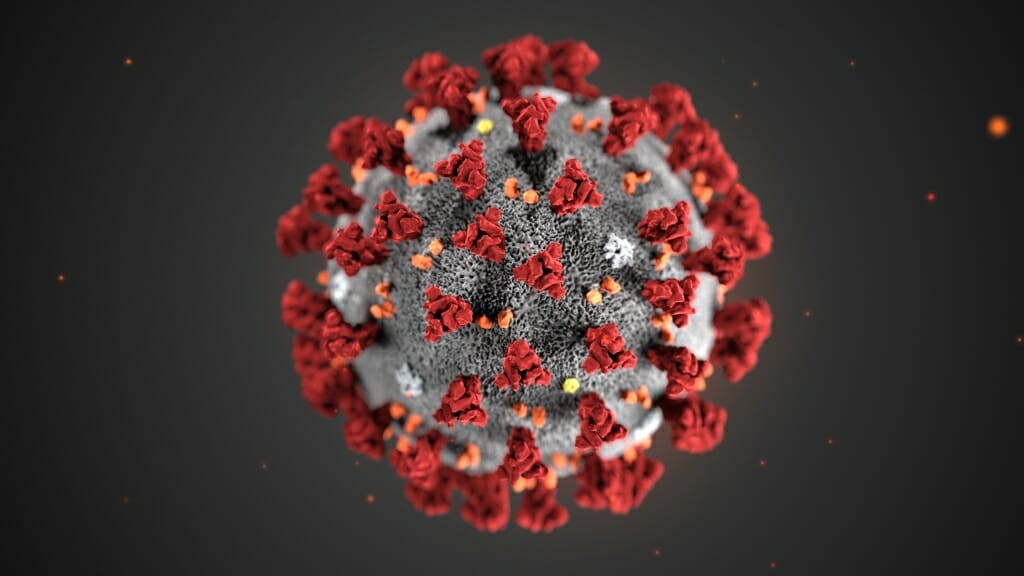

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), portrayed in an illustration created at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM

Before a packed room at the Health Sciences Learning Center on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus on Jan. 29, Associate Dean for Public Health and Community Engagement Jonathan Temte asked for a moment of silence for those affected by an outbreak of a virus that in a matter of weeks has sickened nearly 10,000 people around the world and killed more than 200 people in China as of Jan. 31.

The virus, a previously unknown member of a class of coronaviruses, was first described in late December 2019 after several cases of illness appeared in people in Wuhan, a city in Hubei province, China. Its name, for now, is “2019-nCoV.”

As details of the virus and its effects continue to emerge, UW–Madison gathered a panel of experts, including physicians, epidemiologists, public health officials, scientists and communication experts, to address questions and concerns from the public.

Watch a video of the livestreamed event.

Nasia Safdar, medical director of infection control at UW Hospital and Clinics, discusses preparations the hospital and health care workers have made in light of the new coronavirus. Photo: Todd Brown

The event came together on short notice after the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Robert R. Redfield, had to cancel his previously scheduled talk in Madison in order to help manage the outbreak.

Here are some takeaways:

Coronaviruses are relatively common. What makes this coronavirus unique is that it has never been implicated in human disease before. “There are several human coronaviruses that cause mild disease and we have known about them for decades now,” said Kristen Bernard, a professor in the UW School of Veterinary Medicine. “They are the cause for about 30 percent of common colds.” They are also the viruses behind the 2003 SARS and 2012 MERS outbreaks, which both killed large numbers of people.

The original source of the virus is probably bats, which serve as a reservoir for large numbers of zoonotic diseases, or those that pass between animals and people. Most of these viruses rely on an intermediary species to render it infectious in people. With SARS, experts believe that species was civet cats, and with MERS, it was dromedary camels. Some early reports blamed snakes for the 2019-nCoV outbreak, but, said Chris Olsen, emeritus professor in the School of Veterinary Medicine: “I think we need to take that with a very large grain of salt.”

In people, 2019-nCoV is transmitted through coughing and contact with saliva, mucus or the tears of people sick with the virus. Symptoms of illness include cough, fever and shortness of breath. Public health officials are still working to determine whether infected people can transmit the virus to others if they are not symptomatic.

There have been six confirmed cases of 2019-nCoV in the United States since mid-January, and as of Jan. 30, officials in the U.S. reported the first case of person-to-person transmission. There have been no confirmed cases in Wisconsin, though experts continue to monitor patients for symptoms and have sent six potential cases to the CDC for testing. One came back negative for the virus and results are still pending on the remaining samples. Allen Bateman, assistant director in the communicable disease division of the Wisconsin State Lab of Hygiene, said the laboratory is working with local health departments and clinical labs across the state to help with testing and response.

There are no specific cures or treatments for people with 2019-nCoV, but as is the case with many viruses, said Medical Director of Infection Control at UW Hospital and Clinics Nasia Safdar, those who are sick are offered supportive care to relieve symptoms and mitigate complications. And because the symptoms of the novel coronavirus are similar to other kinds of viruses, she and colleagues are working with health care providers to train them on containment and help keep them safe.

There are no cases of 2019-nCoV in Wisconsin at this time, but “we are prepared to react if things are changing,” said Patrick Kelly, interim director of medical services at University Health Services. On campus, that has meant taking steps to keep more than 40,000 students safe and provide physical and mental health care as needed. It has also meant communicating often with students and their families. An all-campus message sent Jan. 24 shared information about the novel virus and was translated on short notice in five languages.

The state has also been working on the logistics of monitoring and preparing for the virus, said School of Medicine and Public Health (SMPH) Professor of Medicine Ryan Westergaard, also chief medical officer and state epidemiologist at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. While some areas have couriers to transport samples from the clinic to the state lab for testing, police are serving that role in others. “It’s been a good learning experience,” he said, “with people from legislative offices and the governor’s office at the table to make sure we are coordinating well.”

It’s important to be prepared for a possible outbreak of coronavirus, but public health officials still remain more concerned about seasonal influenza. That virus has had a greater impact in Wisconsin, and in the U.S., so far this year. “Right now, in Dane County and southern Wisconsin, we’re in the midst of a huge influenza outbreak,” said Temte, also a family medicine physician. “As of Friday (Jan. 24), 54 children across the country had died of influenza … and influenza is one of these diseases for which we have effective vaccines and effective antivirals.”

Allen Bateman from the Wisconsin State Lab of Hygiene discusses how the agency has prepared to receive and test samples from potentially symptomatic patients in the state. Photo: Todd Brown

Scientists at UW–Madison are monitoring research developments globally. Chinese scientists worked swiftly in the aftermath of the outbreak to decode the genetic sequence of 2019-nCoV and share it with other researchers worldwide. Thomas Friedrich, a professor in the School of Veterinary Medicine, said some researchers are working with that sequence to develop vaccines against the new coronavirus. Some journals where scientists publish, including the New England Journal of Medicine, require researchers to share their raw data for others to use, and many researchers are making data instantly available on widely-used pre-print servers. “I think it’s very important for us to make our information available to the public as much as possible,” he said.

Misinformation is easy to spread, so sticking with facts when discussing 2019-nCoV is imperative, said Emily Kumlien, media strategist at UW Health. “We work with the experts to get the right information to share with the community at the right time.” That includes using social media and other platforms to reach people in the places where they get their news, and where misinformation is most likely to live. “I think it’s everybody’s responsibility,” said Ajay Sethi, SMPH professor of population health, “to serve as educated, informed opinion leaders; to identify misinformation; and to find creative and strategic ways to dispel that.”

Officials believe the novel coronavirus originated in a seafood and live animal market in Wuhan. But shutting down these kinds of markets broadly would be akin to “telling Wisconsinites not to hunt deer,” said Bernard. “That’s part of their culture and we have to be sensitive to that.” However, she added: “There are things we can do and that’s why basic research is so, so important.”