Happy birthday – and Father’s Day – to Bascom Hall

Bascom Hall has become a symbol of UW–Madison. It received that name a century ago on June 22. Photo: Jeff Miller

Books and ties are perfectly fine Father’s Day gifts. Useful. Practical.

But a building? Now that’s a gift that really makes a statement.

Bascom Hall turns 100 on June 22. Only 100? We don’t mean to be rude but it, ahem, looks a bit older. And it is.

The building at 500 Lincoln Drive started out being called University Hall or Main Hall when it opened in 1859.

But thanks to a devoted daughter, it was renamed Bascom Hall on June 22, 1920.

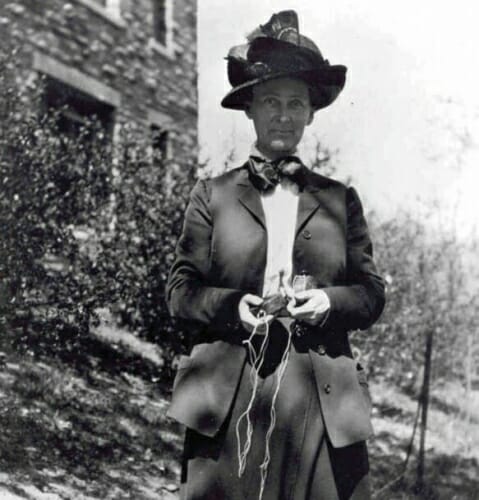

Florence Bascom was proud of her father John Bascom because he was a strong early advocate for women in academia.

She proposed renaming University Hall in her father’s honor, and on June 22, 1920, a formal dedication took place.

“John Bascom came to Wisconsin at the beginning of the period of co-education for men and women,” Josephine Sales Simpson, ’83 (that’s 1883), said at the ceremony. “Five years previously the first woman had received her degree from this university. His attitude was one of profound faith in women. This faith permeated all of his work, and one of his great influences was in his giving to the women of his time faith in their own powers.”

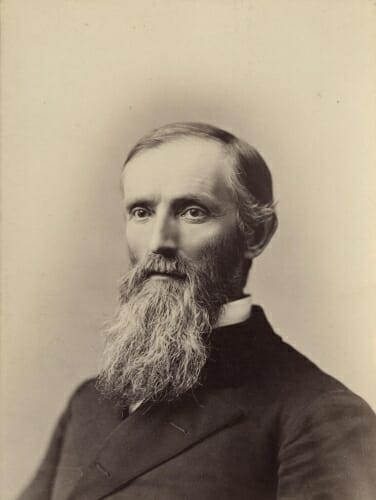

John Bascom was born in Genoa, New York on May 1, 1827. He graduated from Williams College in 1849 and from Andover Theological Seminary in 1855. Bascom taught rhetoric and English literature at Williams until he moved his wife and five children to Madison in 1874 when he became president of UW–Madison, serving until 1887.

During his administration the university opened the first Agricultural Experimental Station, the School of Pharmacy, Washburn Observatory, Old Science Hall and Assembly Hall. He attracted more financial support and better teachers to the university. He believed in the new science of psychology, and lectured and wrote numerous books and articles on the subject.

And he opposed the policy of separate classes for men and women, allowing co-education instruction at the university.

Florence, the youngest of his five children, was proud of her father’s legacy.

She was particularly irked that, during a trip visiting with the “ridiculously young” alumni of the University at Philadelphia she had “been forced to recognize the fact that the name of John Bascom is quite unknown among them,” she wrote to UW President Edward Birge.

But they had heard of former president Paul Chadbourne, a bitter opponent of coeducation. When Birge was proposing renaming buildings after former presidents, naturally he thought it fitting to rename Ladies Hall to what it is now known as today – Chadbourne Hall.

Birge explained his reasoning in a 1922 letter. “First, President Chadbourne secured the appropriation for the building. My second reason is a private one rather than public. I thought it was only fair that Dr. Chadbourne’s contumacy regarding coeducation should be punished by attaching his name to a building which turned out [to be] one of the main supports of coeducation.”

A funny historical footnote, but it didn’t sit right with Florence that more people had heard of Chadbourne than her father, who died in 1911. She wrote to Birge that it was “the irony of fate that the name of Chadbourne, whose stay was so brief and whose influence was relatively so ephemeral, should be known to every alumnus of the University.”

So she proposed renaming University Hall after her father.

John Bascom’s faith in women seems to have deeply influenced Florence, who went on to an extremely successful career in Geology.

Growing up, she was encouraged by her father and her mother, an activist in the suffrage movement, to pursue science. She attended the University of Wisconsin, receiving her BA degree in 1882 and her MA degree in 1884, and was the first woman to be granted a PhD from Johns Hopkins University in 1893.

Being first didn’t come without a fight. The president of Johns Hopkins, Daniel C. Gilman opposed the co-education of women. But Bascom persisted, successfully petitioning for admission with support from her Wisconsin professors as well as her father.

She was required to sit behind a screen in the corner of the classroom – so she wouldn’t distract the male students. When she graduated in 1893, Gilman sent her a letter of congratulations: “You have won your honors, as you must have wished to win them, without any favoritism, – just as all other candidates among us have won their diplomas, by talents, patience, and exertion…”

Florence Bascom was the first woman fellow of the Geological Society of America. In 1924 she became councilor and in 1930 Vice President of that organization. From 1896 to 1905, she was the editor of The American Geologist. She was also a member of the National Academy of the National Research Council and the Geophysical Union and other scientific societies.

From 1895 to 1928, Bascom taught at Bryn Mawr College, where she established the Geology Department. In 1896, she became the first woman appointed to the United States Geological Survey.

She is credited as the first professional female geologist to survey Mount Desert Island in Acadia National Park in Maine, publishing “The Geology of Mount Desert Island” in 1919.

Florence Bascom taught many women who went on to follow in her groundbreaking footsteps. In 1937, 8 out of 11 of the women who were Fellows of the Geological Society of America were graduates of Bascom’s course at Bryn Mawr College.

“When any woman manifests an interest in the science [of geology] I am always glad to tell her of its possibilities and she makes her own choice. Not only must a girl have the mental aptitude for scientific research, but also physical strength and great physical courage. Then too she must be strong in the conviction that it is the work she really wants to do,” wrote Florence Bascom.

That doesn’t mean it was easy. When she used to complain to her father about male students and faculty staring at her, he offered, “you better put a stone or two in your pockets to throw at those ‘heads that are thrust out of windows.'”

Florence died June 18, 1945 at the age of 82.

She was raised to pursue what she believed in. And she believed her father deserved recognition.

Tags: facilities, history