Global warming forecasts creation, loss of climate zones

A new global warming study predicts that many current climate zones will vanish entirely by the year 2100, replaced by climates unknown in today’s world.

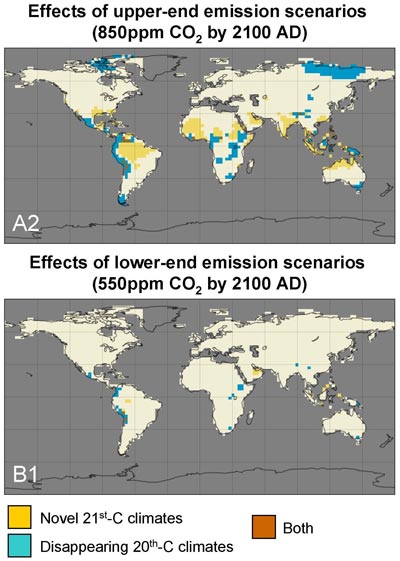

A new climate modeling study has identified regions of the world where greenhouse gas emissions during the next century are likely to cause the appearance of novel climates unlike anything that exists today, shown in yellow in this image created this month, and regions whose current climates will disappear completely by the year 2100, shown in blue. Novel climates appear throughout the tropics and subtropics, while the climates now found in tropical mountain ranges and near the poles may vanish. The work, led by UW–Madison geographer Jack Williams, suggests that climate change is likely to have serious ecological impacts, including increased risk of extinction.

Image: courtesy Jack Williams

Global climate models for the next century forecast the complete disappearance of several existing climates currently found in tropical highlands and regions near the poles, while large swaths of the tropics and subtropics may develop new climates unlike anything seen today. Driven by worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, the climate modeling study uses average summer and winter temperatures and precipitation levels to map the differences between climate zones today and in the year 2100 and anticipates large climate changes worldwide.

The work, by researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the University of Wyoming, appears online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences during the week of March 26.

As world leaders and scientists push to develop sound strategies to understand and cope with global changes, predictive studies like this one reveal both the importance and difficulty of such a task. Primary author and UW–Madison geographer Jack Williams likens today’s environmental analysts to 15th-century European mapmakers confronted with the New World, struggling to chart unknown territory.

“We want to identify the regions of the world where climate change will result in climates unlike any today,” Williams says. “These are the areas beyond our map.”

The most severely affected parts of the world span both heavily populated regions, including the southeastern United States, southeastern Asia and parts of Africa, and known hotspots of biodiversity, such as the Amazonian rainforest and African and South American mountain ranges. The changes predicted by the new study anticipate dramatic ecological shifts, with unknown but probably extensive effects on large segments of the Earth’s population.

“All policy and management strategies are based on current conditions,” Williams says, adding that regions with the largest changes are where these strategies and models are most likely to fail. “How do you make predictions for these areas of the unknown?”

Using models that translate carbon dioxide emission levels into climate change, Williams and his colleagues foresee the appearance of novel climate zones on up to 39 percent of the world’s land surface area by 2100, if current rates of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions continue. Under the same conditions, the models predict the global disappearance of up to 48 percent of current land climates. Even if emission rates slow due to mitigation strategies, the models predict both climate loss and formation, each on up to 20 percent of world land area.

The underlying effect is clear, Williams says, noting, “More carbon dioxide in the air means more risk of entirely new climates or climates disappearing.”

In general, the models show that existing climate zones will shift toward higher latitudes and higher elevations, squeezing out the climates at the extremes — tropical mountaintops and the poles — and leaving room for unfamiliar climes around the equator.

“This work helps highlight the significance of changes in the tropics,” complementing the extensive attention already focused on the Arctic, says co-author John Kutzbach, professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at UW–Madison. “There has been so much emphasis on high latitudes because the absolute temperature changes are larger.”

However, Kutzbach explains, normal seasonal fluctuations in temperature and rainfall are smaller in the tropics, and even “small absolute changes may be large relative to normal variability.”

The patterns of change foreshadow significant impacts on ecosystems and conservation. “There is a close correspondence between disappearing climates and areas of biodiversity,” says Williams, which could increase risk of extinction in the affected areas.

Physical restrictions on species may also amplify the effects of local climate changes. The more relevant question, Williams says, becomes not just whether a given climate still exists, but “will a species be able to keep up with its climatic zone? Most species can’t migrate around the world.”

For the researchers, one of the most poignant aspects of the work is in what it doesn’t tell them — the uncertainty. At this point, Williams says, “we don’t know which bad things will happen or which good things will happen — we just don’t know. We are in for some ecological surprises.”

The work was conducted in collaboration with Stephen Jackson at the University of Wyoming and was funded by the National Science Foundation.