Exhibits reveal famous patrons of the arts also loved science

Cristoforo Munari, “Still-life with Porcelain Vases, Flute, Books, and Oranges,” 1706–1713. This and other pieces will be on display at the Chazen Museum of Art through Oct. 21.

Image: courtesy Chazen Museum of Art

In the early 1600s, they offered valuable support to the astronomer Galileo. Later, they founded an academy of science, inviting the scholars to conduct experiments inside one of their palaces. And in the 1700s, they regularly commissioned detailed portraits of the animals and plants raised on their lands.

“These people were fascinated with oddities, partly because they were exotic, but also because the Medici were deeply engaged in experimentation. So these things went right into the paintings.”

Gail Geiger, professor of art history

Who was this band of early science enthusiasts? It was none other than the ruling Florentine family, the Medici, a clan better known for its ruthless politics, business acumen and — above all — patronage of great Renaissance artists such as Botticelli and Michelangelo.

Medici enthusiasm for science as well as art during the three centuries the family reigned over Florence and Tuscany is now on display at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Through a rare books exhibition, "Under the Medicean Stars: Medici Patronage of Science and Natural History, 1537-1737," in the Department of Special Collections, UW–Madison Libraries, visitors learn that the Medici valued science both for practical and theoretical reasons.

Meanwhile, an art exhibit, "Natura Morta: Still-Life Painting and the Medici Collections," at the Chazen Museum of Art shows how the family’s scientific interests helped fuel an explosion of the still-life genre (called "natura morta" in Italian) during the Baroque period in Florence.

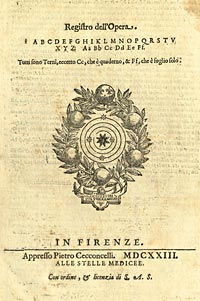

Embellishment of the Medicean coat of arms by Pietro Cecconcelli is currently on exhibit as part of “Under the Medicean Stars: Medici Patronage of Science and Natural History, 1537-1737” in the Department of Special Collections through Oct. 26.

Image: courtesy Chazen Museum of Art

Given our custom today of strictly separating the arts and sciences, the Medici passion for both may seem surprising. But at the time, pursuit of both disciplines was common, says art history professor Gail Geiger, who will give an overview of the "Natura Morta" exhibit at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, Sept. 12, at the Chazen, 800 University Ave., Madison.

She points out that Leonardo da Vinci is remembered as much for his scientific ideas as for the masterworks of High Renaissance art he created. And Galileo — who, after discovering the moons of Jupiter, dubbed them the "Medicean Stars" to secure the family’s patronage — wrote poetry that is still taught today.

"People like Leonardo crossed back and forth between science and what we now call the fine arts," Geiger says. "The disconnect between the humanities and the sciences was a later development."

Geiger further explains that despite working as bankers and becoming immersed in city government and commerce, the Medici kept strong ties to the villas they maintained on working farms. Not only did these country places provide fresh produce and game, but they often also had elaborate ornamental gardens.

What the villas also had in abundance was wall space, which the family increasingly filled with commissioned and collected still-life paintings of flowers, vegetables and animals. They especially prized specimens that were monstrously sized, oddly shaped or otherwise unusual.

"These people were fascinated with oddities, partly because they were exotic, but also because the Medici were deeply engaged in experimentation," says Geiger. "So these things went right into the paintings."

Cristoforo Munari, “Vases, Glass, and Fruit,” 1706–1713, oil on canvas.

Image: courtesy Chazen Museum of Art

For example, a Medici court physician and natural philosopher named Francesco Redi once convinced the artist Bartolomeo Bimbi to immortalize a double-headed calf in a painting, says Geiger. The Medici also hired Bimbi to paint numerous portraits of fruits and vegetables, including the more than 100 citrus varieties cultivated in Tuscany in the early 1700s. Bimbi did this with such artistic skill and scientific precision that the works are considered both masterpieces of still-life painting and important historical documents in botanical classification.

But natural history wasn’t all. Besides pursuing science for its own sake, the family’s "interest in state craft" meant they were curious about many other subjects, says Robin Rider, science historian and curator of Special Collections.

For example, their interest in military fortifications and artillery fueled the field of applied mathematics, while concerns for their subjects’ health prompted investigations into the medicinal uses of plants. Likewise, the need to dredge ports and maintain navigable rivers spurred studies of hydraulics and river flow.

True to the Medici spirit, "Under the Medicean Stars" was itself created through interdisciplinary effort. In collaboration with Rider of the Department of the History of Science, and Geiger of the Department Art History, graduate student Meghan Doherty put the exhibition together from Special Collections’ extensive science and natural history holdings — among the finest in the country. "This project offered such a rich environment for exchange," says Geiger, "and a reminder that the arts and sciences can be collaborative."

"It was great fun — all those gorgeous books," adds Rider. "When you have so much to choose from, you know you’ve hit upon a good topic."

For more information on the Natura Morta exhibit and its accompanying programs, contact the Chazen Museum of Art at (608) 263-2246.

For more information on "Under the Medicean Stars," contact the Department of Special Collections, UW–Madison Libraries, at (608) 262-3243.

Giovanna Garzoni, “Ceramic Bowl with Pears and Morning Glories,” 1651–1662, tempera on parchment.

Image: courtesy Chazen Museum of Art

Tags: arts, College of Letters & Science, events, history