Earth’s vegetation is changing faster today than it has over the last 18,000 years

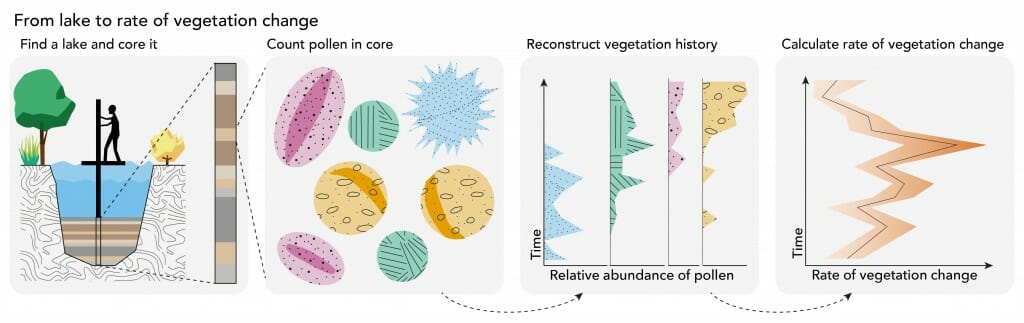

To study past plant ecosystems and how they changed, a lake or other suitable environment is cored to retrieve the layered sediments which usually contain pollen grains that accumulated over thousands of years. By identifying and counting the different pollen grains researchers can then reconstruct the local vegetation composition. Finally, the rate of vegetation change is estimated from the changes in pollen abundances through time. Artwork by Milan Teunissen van Manen

MADISON – A global survey of fossil pollen has discovered that the planet’s vegetation is changing at least as quickly today as it did when the last ice sheets retreated around 10,000 years ago.

Beginning some 3,000-to-4,000 years ago, Earth’s plant communities began changing at an accelerating pace. Today, this pace rivals or exceeds the rapid turnover that took place as plants raced to colonize formerly frozen landscapes and adapt to a global climate that warmed by about 10 degrees Fahrenheit.

The research, published May 20 in Science, suggests that humanity’s dominant influence on ecosystems that is so visible today has its origin in the earliest civilizations and the rise of agriculture, deforestation and other ways our species has influenced the landscape.

Researchers collecting a core sample in St. Paul, Alaska. Photo by Jack Williams

This work also suggests ecosystem rates of change will continue to accelerate over the coming decades, as modern climate change further adds to this long history of flux. And by showing that recent biodiversity trends are the start of a longer-term acceleration in ecosystem transformations, the new study provides context for other recent reports that global biodiversity changes have accelerated over the last century.

An international collaboration of scientists led the new analysis, which was powered by an innovative database for paleoecological data. The Neotoma Paleoecology Database is an open-access tool that gathers and curates data on past ecosystems from hundreds of scientists. Neotoma is chaired by University of Wisconsin–Madison professor of geography Jack Williams, who helped lead the new research.

The study authors analyzed more than 1,100 fossil pollen records from Neotoma, spanning all continents except Antarctica, to understand how plant ecosystems have changed since the end of the last ice age about 18,000 years ago, and how quickly this change occurred.

“At the end of the ice age, we had complete, biome-scale ecosystem conversions,” says Williams, who also curates Neotoma’s North American pollen database. “And over the past few thousand years, we’re at that scale again. It has changed that much. And these changes began earlier than we might have thought before.”

Fossil pollen provides an extremely sensitive measure of past plant communities. As pollen from surrounding plants falls into lakes, it settles in layers from oldest at the bottom to newest at the top. Scientists can extract sediment cores and conduct the painstaking work of identifying pollen and reconstructing plant ecosystems over thousands of years.

Yet each sediment core only provides information about one place on Earth, so true global-scale analyses of past vegetation change require the amassing and curating of many such records. Neotoma has gathered thousands of such datapoints to help scientists uncover global trends. Researchers from the University of Bergen in Norway, UW–Madison, and Neotoma data stewards from around the world collaborated to perform the new analysis.

Using these pollen records, the team applied new statistical methods to better analyze how quickly plant communities have changed in the last 18,000 years.

They discovered that the rate of change initially peaked between 8,000 and 16,000 years ago, depending on the continent. These continental differences are likely caused by different timing and patterns of climate change linked to retreating glaciers, rising carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere, changes in Earth’s orbit, and changes in ocean and atmospheric circulation.

Ecosystems then stabilized until about 4,000 years ago. Then, the rate of change began a meteoric rise that continues today, when most plant ecosystems are changing at least as fast as they did at the peak of ice-age-induced flux.

“That was a surprising finding, because over the last few thousand years, not a whole lot was happening climatically, but the rates of ecosystem change were as big or bigger than anything we’ve seen from the last ice age to the present,” says Williams.

Although this analysis of pollen records was focused on detecting ecosystem changes, rather than formally determining causes, these recent ecosystem changes correlate with the beginning of intensive agriculture and the earliest cities and civilizations around the world.

Williams says that one intriguing feature of these analyses is that the early rise is so early worldwide, even though each continent had different trajectories of land use, agricultural development and urbanization.

Scientists have coined the term the Anthropocene to describe the modern geological period, when humans are the dominant influence on the world. “And one of the questions has been, when did the Anthropocene begin?” says Williams. “This work suggests that 3,000 to 4,000 years ago, humans were already having an enormous impact on the world (and) that continues today.”

A sobering implication from this work, say the scientists, is that in the past, the periods of ecosystem transformations driven by climate change and those driven by land use were largely separate. But now, intensified land use continues, and the world is warming at an increasing rate due to the accumulation of greenhouse gases. As plant communities respond to the combination of direct human impacts and human-induced climate change, future rates of ecosystem transformation may break new records yet again.

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation (grants 1550707, 1550805, and 1948926).

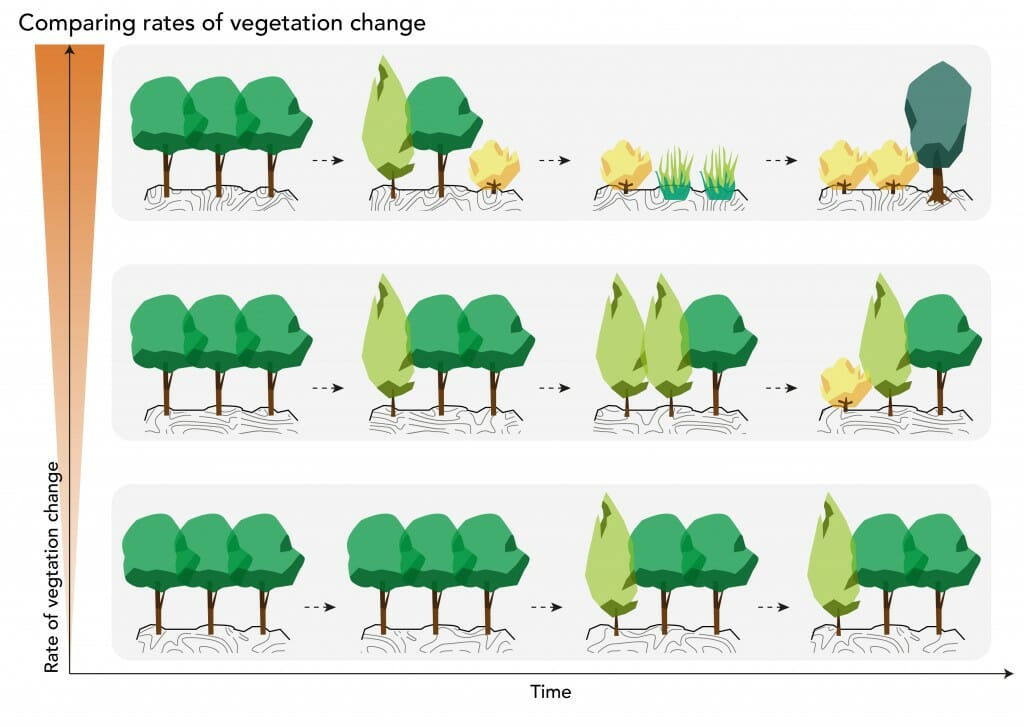

In biodiversity science, a key question is understanding how quickly ecosystems change over time. Ecosystems that undergo large changes in species composition in a very short time will have high rates of change. Artwork by Milan Teunissen van Manen

Tags: climate change, geography, research