DNA analysis provides insight into Mongol Empire’s genetics and integration with local cultures

Are one in 200 men really related to Genghis Khan? Maybe not, according to a new study from researchers at UW–Madison.

In present day Kazakhstan, both local folklore and genetic evidence found buried in royal tombs have shone a light on the region’s ties to Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire. New DNA analysis of ruling elites from the Golden Horde—the northwestern extension of the Mongol Empire—reveals implications for the genetic ancestry of the broader Mongolian Empire. The findings were recently published in Proceeding of National Academy of Sciences.

“Even though the medieval genetic landscape of Central Eurasia is already known thanks to previous studies, we believe this is the first ancient DNA evidence to support the genomic ancestry of ruling elites in the Golden Horde,” says Ayken Askapuli, lead author of the study and PhD candidate at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The Golden Horde was founded and ruled by Genghis Khan’s eldest son, Joshi, and his descendants. According to local folklore, one of the four tombs analyzed for this study belongs to Joshi himself and houses his remains. The additional three tombs analyzed in this study belonged to other Golden Horde ruling elites and provide evidence of Mongol cultural practices blending with local culture.

Inspired, Askapuli and his archaeologist colleagues in Kazakhstan decided to investigate whether the tales were true, in collaboration with researchers at the National Institute of Genetics, Japan.

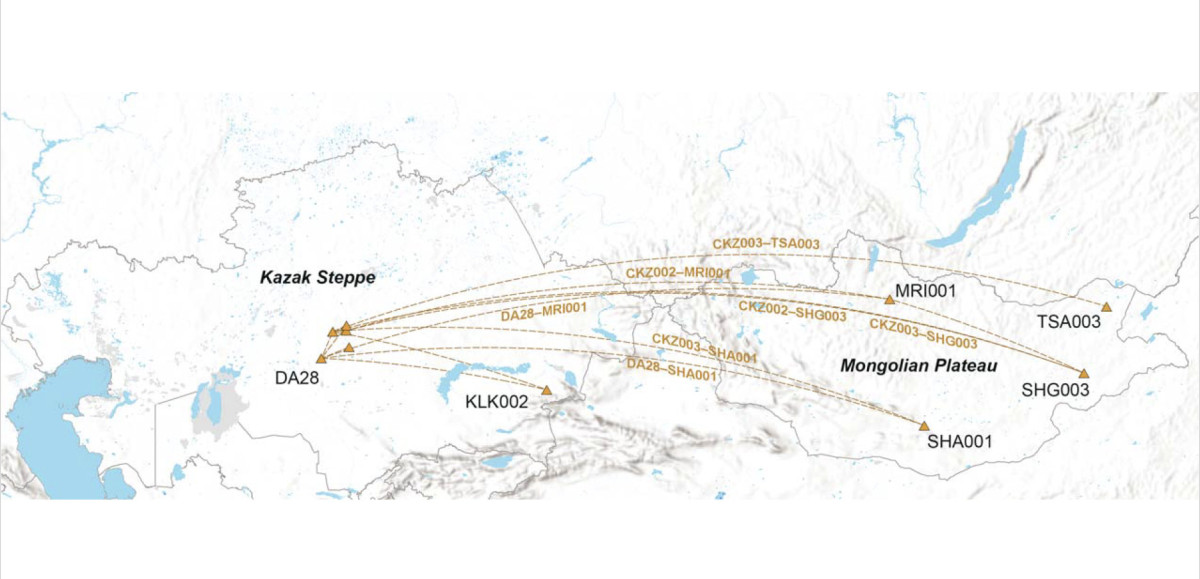

“It’s kind of like forensics,” Askapuli says. “By analyzing their genome, we determined these four Golden Horde individuals trace their ancestry back to the Mongolian plateau. We saw evidence that their Y-chromosomes are part of a branch of the C3* cluster.”

About twenty years ago, researchers traced fragments of DNA found on the Y-chromosome, called the C3* cluster, back to medieval inhabitants of the Mongolian Plateau. Today, many people across central Eurasia have this C3* cluster in their genome. Some scholars have hypothesized one reason the C3* cluster is so widespread is because of the Mongol Empire’s vast sphere of control. It’s even fueled the popular belief that one in 200 men is related to Genghis Khan.

But Askapuli and his collaborators’ data reveal a more complicated possibility: While they did find evidence of the C3* cluster in the genome of the ruling elites, it appears in the genome of modern individuals at a much lower frequency.

“With ancient DNA results, we can distinguish different branches of the genome that are close to each other but are not identical,” says UW–Madison professor and paper co-author John Hawks. “The one that Askapuli has found in the Golden Horde ruling elites is a branch of the C3* cluster but it’s not as common as the larger branch.”

That leaves the question: Which genetic branch, if any, is in Genghis Khan’s genome? It could make sense for the ruling elite class of an empire to share a similar genomic background. If the Golden Horde was established by descendants of Joshi, could the genomes of these elites be similar to that of the famous ruler’s?

Until Genghis Khan’s own burial place is discovered, researchers can’t say for certain. But thanks to the collaboration between UW–Madison and researchers from Kazakhstan and Japan, scholars now have a better idea of what the ruling class’s genome might look like, giving them more avenues to explore. Askapuli plans to continue this work, possibly using data from modern-day genomes and advanced techniques to better build out the region’s genomic connections across time.