Coming full circle, new graduate makes a difference in women’s health

On Sunday, May 15, Wren Keturi will graduate from UW–Madison with a bachelor’s degree in gender and women’s studies with an emphasis on biological anthropology. Less than 24 hours later, she will put her degree to work.

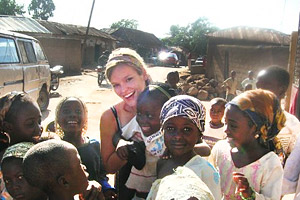

Spring 2011 graduate Wren Keturi poses with children in Naraguta Village, Nigeria during the summer of 2008. The day after graduating with a major in Gender and Women’s Studies, she will travel to Kenya to study the relationship between gender and malarial infection. She plans to pursue a master’s degree in public health.

Photo: courtesy Wren Keturi

In a story connecting many parts of the UW–Madison experience, Keturi has brought her appreciation for the women who raised her into a career helping women — and those they care for — around the world.

She and mentor Araceli Alonso, senior lecturer in gender and women’s studies, will join eight other UW–Madison students in rural Kenya to support Alonso’s continuing Health by Motorbike project.

Keturi grew up in tiny Chillicothe, Ill., raised by strong female role models: her mother and grandmother.

“For a lot of women, health is a huge barrier to access to education and the lives that they want to live,” says Keturi, who will graduate at the commencement ceremony at 10 a.m. on May 15. “I grew up in a female-centered family, led by my mom and my grandma, and I was always frustrated that certain health aspects in both of their lives prevented them from doing what they wanted to do.”

Keturi began considering UW–Madison as she drove her grandmother to repeated appointments for a Wisconsin Women’s Health Initiative study. The world-renowned physician leading her grandmother’s care turned out to be the only other person from Keturi’s small high school to attend UW–Madison.

Given her low-income background, Keturi credits many programs on and off campus for making her education possible. Before joining the McNair Scholars last year, she hadn’t considered graduate school. Now, after only one year instead of the typical two, she will move to Oregon to pursue a fully funded master’s degree in international public health.

In the summer of 2008, Keturi traveled to Nigeria, volunteering in a health clinic with a student organization. However, she left early after contracting malaria.

“I was so struck by the fact that I was able to fly back for treatment, but I left behind so many people in Naraguta Village who aren’t able to do that,” says Keturi. “That’s their home, that’s their reality. Getting malaria changed my whole perspective on what I want to do.”

In many of these remote African villages, gender and family dynamics have a huge impact on malaria’s transmission and treatment. Women may need to ask permission before seeking treatment; they may give medicine to their children before treating themselves.

Already, the connections made through Alonso’s malaria campaign have increased health literacy and trust of clinical workers, providing safer and more empowering access to health services.

The trip to Kenya brings Keturi’s life full circle. She will collect more formal data to measure the effects of the malaria campaign (funded for two years running by Wisconsin Idea fellowships). Upon her return, she will complete a research paper, cementing a collaboration with Alonso that she plans to continue through graduate school.

“Getting malaria was scary, but it opened my eyes,” says Keturi. “Everything continues to make this great circle. Even the bad things have worked out really well.”

The Health by Motorbike project, a two-year recipient of a Wisconsin Idea grant for its malaria campaign, is itself the result of remarkable connections between UW–Madison and alumni around the world. Watch videos and learn more about the project.