Advanced alloy firm cuts costs with help from UW’s ‘lean operations’ expertise

Winsert Inc., a Marinette, Wisconsin, supplier of high-tech metal and parts to manufacturers around the globe, continues to gain from its longstanding relationship with Engineering Professional Development at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Founded in 1977, Winsert uses 21st century metallurgy to make alloys that resist corrosion, wear and high temperature. Its products are used in engines, power generation, emission controls, industrial valves, food processing and wood processing. The company has 184 employees.

Pouring precision parts made from high-tech alloys leaves little room for error. Courtesy of Winsert Inc.

The production challenge at Winsert shares essential features with the challenges facing scores, perhaps hundreds, of Wisconsin manufacturers. “Small-batch manufacturing is a three-dimensional maze, governed by the all-important fourth dimension of time,” says EPD program director Jeff Oelke. “You get orders, and each has a different deadline, a different quantity, for a different material and product that needs to pass through a particular set of machines — each in the correct sequence, obviously, and each occupying its own set of operators.”

Balancing these needs, while keeping an eye out for incoming rush orders, is one of Oelke’s areas of expertise.

This realm, called “lean operations,” requires focus, measurement, reassessment, and more focus. Some changes seem obvious: A workstation, for example, should only hold the necessary materials and equipment, laid out in a logical order. A material rack should not have materials discontinued last year.

Many lean-operations tactics are more subtle. Machine oil, for example, can be replaced on a regular schedule, but savings can accrue if it is tested and replaced only when nearly exhausted. Similarly, instead of waiting for a motor to fail, it can be monitored for electrical, thermal and mechanical signs of impending failure. Predicting failure allows a replacement during downtime that does not impede production.

Overall, the changes in lean operations can sum to significant savings in cost and time. And it is here that Winsert excels, Oelke says. “They have been more diligent than most manufacturers in extracting the maximum value from lean operations.”

“The change I’ve seen regarding how maintenance was prioritized and conducted has been refreshing,” says Eugene Lemery, Winsert’s facility manager. “The culture was to ‘keep machines going,’ but now it is about having them maintained and analyzing the data from these maintenance activities to better plan preventative and predictive maintenance.”

Precision knowledge of actual operations translates into cost reductions and better performance, Lemery says. “We have more carefully scrutinized our new equipment spare parts list for an eye for reducing our maintenance, repair and operating supply stores expense, and increasing machine uptime.”

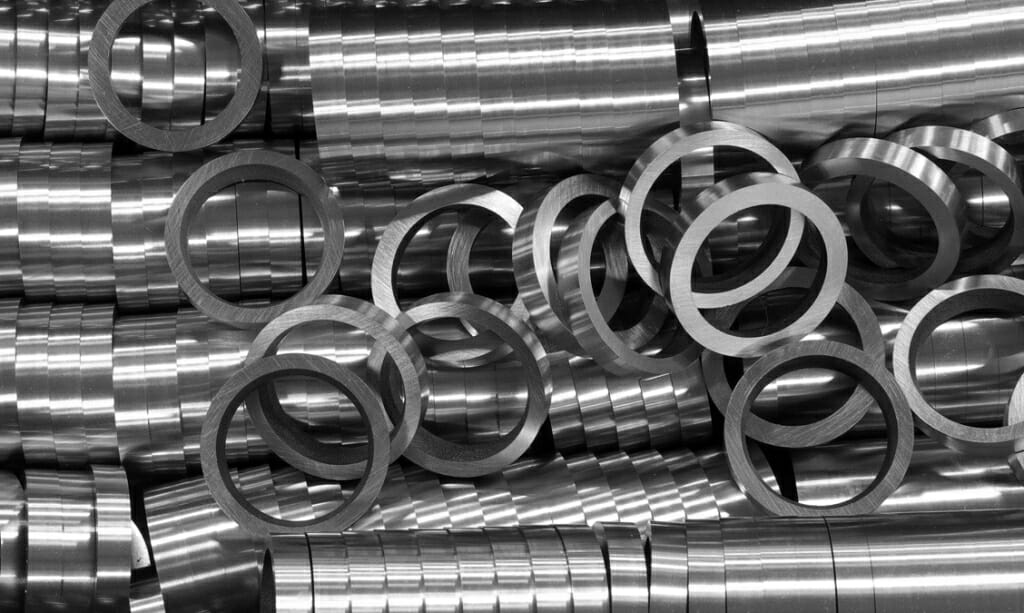

These identical rings will likely find themselves at the center of an extreme duty part. UW–Madison Engineering Professional Development

As Lemery indicates, lean operations can affect both sides of the balance sheet. Customers need and reward on-time delivery of orders. But maintenance costs money, Lemery observes. “I’ve also noticed a change in that the maintenance is looked at as a business strategy, and costs of repairs, failures and parts inventories expenses are carefully considered.”

Each year, EPD offers 256 courses for engineering and technical professionals. Adult students from Wisconsin and across the nation attend courses in Madison, Chicago, Florida or at an employer’s site.

Winsert staff, right up to the owners, have been involved in EPD manufacturing courses for more than 10 years.

Oelke, who has worked in Wisconsin manufacturing for 25 years, says Winsert’s results are evident even on a casual walk through the factory. “They have several dozen machine tools, and it’s a very clean and pleasant work environment, which is not true of many machine shops. You see a sense of urgency to get things done, but they are not in firefight mode.”

Winsert makes actuators, bearings, rings, seals and more at its factory in Marinette, Wisconsin. Photo Illustration courtesy of Winsert Inc.

Part of the credit for Winsert’s success goes to a stable leadership team, Oelke says. “They are very thoughtful. When a plan isn’t working as they hope, they take the time to study and examine the underlying cause, rather than abandoning their continuous improvement efforts and going to a whole new strategy. There are so few companies that do this so well.”

In manufacturing, Oelke says, material “needs to flow through the shop in a timely manner. What are all the steps they are going to focus on? Can they quickly change tools to suit the job? Is the facility layout optimal for this flow?”

At Winsert, he says, “they have created a more visual factory so they can see when something is not flowing. They don’t have to wait for a paper report.”

Winsert also developed a visual production planning system that keeps track of orders in real time, Oelke says. “Less than 2 percent of companies adopt that. Winsert perfects the system by never giving up, by never being satisfied.”

Subscribe to Wisconsin Ideas

Want more stories of the Wisconsin Idea in action? Sign-up for our monthly e-newsletter highlighting how Badgers are taking their education and research beyond the boundaries of the classroom to improve lives.