Weather station network to expand across Wisconsin, aiding farmers and others

At sunrise, a weather station is seen in a field at UW–Madison’s Arlington Agricultural Research Station in Arlington, Wisconsin. Thanks to new federal funding and support from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, this station (currently part of Michigan State University’s Enviroweather system) will become part of a Wisconsin network of about 90 weather stations providing vastly improved monitoring of weather and soil conditions. This type of network is called a “mesonet.” Photo by Michael P. King/UW-Madison CALS

Research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison drives innovation, saves lives, creates jobs, supports small businesses, and fuels the industries that keep America competitive and secure. It makes the U.S.—and Wisconsin—stronger. Federal funding for research is a high-return investment that’s worth fighting for. Learn more about the impact of UW–Madison’s federally funded research and how you can help.

A new era for weather data in Wisconsin is on the horizon, thanks to an effort at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Wisconsin weather has become increasingly more unpredictable and extreme since the 1950s, posing challenges for farmers, researchers, and the public. But with the help of a statewide network of weather stations known as a mesonet, the state would be better equipped to deal with the future obstacles of a changing climate.

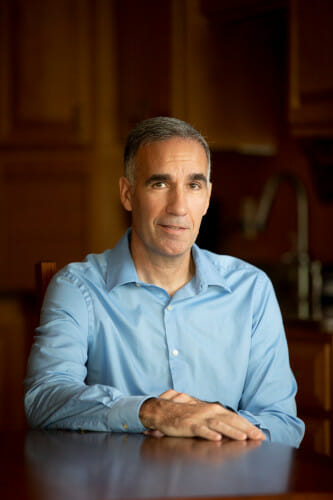

Chris Kucharik, professor of agronomy at UW–Madison, will lead the new Wisconsin Environmental Mesonet project. Photo by Michael P. King/UW-Madison CALS

“Mesonets can guide everyday decision-making for the protection of crops, property, and people’s lives while also supporting research, extension and education,” says Chris Kucharik, professor and chair of the UW–Madison Department of Agronomy, as well as faculty member with the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. Kucharik is leading a major project to expand Wisconsin’s mesonet network with assistance from Mike Peters, director of UW–Madison’s Agricultural Research Stations.

Unlike many other agricultural states, Wisconsin has a minimal network of environmental monitoring stations. Almost half of the 14 weather and soil monitoring stations are at UW research stations, with the others concentrated in Kewaunee and Door counties on private fruit orchards. Data from these stations is currently hosted by Michigan State University’s mesonet.

Moving forward, these stations will move to a designated Wisconsin-based mesonet — called Wisconet — and the total number of stations will increase to 90 to better monitor all regions of the state. This effort is supported by a $2.3 million grant from the Wisconsin Rural Partnership, a U.S. Department of Agriculture-funded UW initiative, as well as $1 million from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation. The expansion of this network is seen as a critical step in providing the highest quality data and information to those who need it.

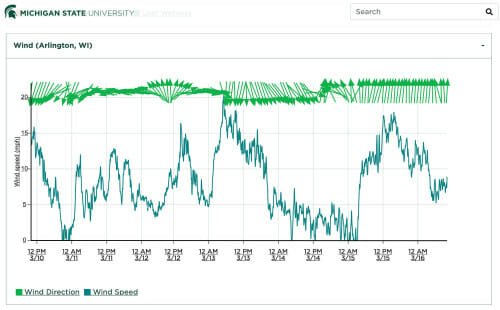

Each station contains equipment to measure atmospheric and soil conditions. Instruments above ground measure wind speed and direction, humidity, air temperature, solar radiation, and liquid precipitation. Below ground, soil temperature and moisture levels are measured at certain depths.

Data from Wisconsin’s existing stations can currently be accessed on Michigan State’s “Enviro-weather” website but will be switched over to a Wisconsin-focused site — at wisconet.wisc.edu — sometime this summer. Kucharik and his team are working to build a simple, open-access site where users can not only view and download station data in real time but find practical guidance for using that data to make real-world decisions.

Wind data for a weather station at UW–Madison’s Arlington Agricultural Research Station in Arlington, Wis., is seen on a Michigan State University website on Thursday, March 16, 2023. Thanks to new federal funding and support from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, this station (currently part of Michigan State University’s Enviroweather system) will become part of a Wisconsin network of about 90 weather stations providing vastly improved monitoring of weather and soil conditions. This type of network is called a “mesonet.” Image by UW–Madison CALS

“Our growers rely on weather data to make important decisions on their farms on a daily basis. It affects when crops are planted, irrigated, and harvested,” says Tamas Houlihan, executive director of the Wisconsin Potato and Vegetable Growers Association (WPVGA). “So we’re very excited about utilizing this expanded mesonet in the near future.”

In February, Kucharik presented the mesonet plan at a WPVGA grower education conference. Andy Diercks, a Wisconsin farmer and frequent collaborator with UW–Madison’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences and Division of Extension, was in the audience and liked what he heard.

“Many of our agronomic decisions are based on weather we’ve experienced, or weather we expect to arrive within the next few hours or days,” says Diercks. “It’s our goal to keep water, nutrients, and crop protectants where plants can use them, but we can’t succeed if we don’t fully understand the current conditions in the air and soil, and what to expect in the near future,” like an unforeseen heavy rain event washing away a recent fertilizer application.

The benefits the environmental mesonet will have for farmers is evident, but many others will benefit as well.

“The National Weather Service regards these networks as valuable because they’re able to verify — and lead to a better understanding of — extreme events,” says Kucharik, who earned his PhD at UW in atmospheric sciences. “A research-grade network of weather stations evenly spread across the state provides the NWS that many more data points.”

While call-in reports from people’s backyard weather stations are valuable, a mesonet can provide a more consistent and complete picture.

Mesonet data could also aid researchers, transportation departments, environmental managers, construction managers and anyone whose work is influenced by weather and soil conditions. There are even opportunities for these stations to help support K-12 education, as school grounds could be a potential home for environmental monitoring stations.

“It’s another way of getting more students connected to something that affects their everyday lives,” says Kucharik. “You can connect that science to all sorts of other fields in agriculture, forestry, and wildlife ecology.”

The installation of Wisconsin’s new mesonet stations is slated to start this summer and is expected be completed in fall of 2026.