Monitoring an invasion: Where are jumping worms now?

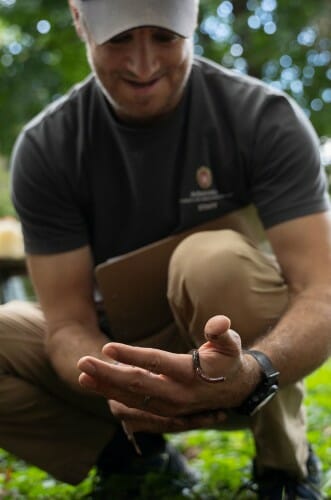

Brad Herrick, the ecologist and research project manager at the UW–Madison Arboretum, pulls an invasive jumping worm out of a Madison backyard as part of a survey aimed at monitoring the species’ population and geographic spread across Dane County. Elise Mahon

The pungent scent of mustard rises from the ground as Brad Herrick pours a gallon jug full of yellow-tinged, milky liquid into a square foot of soil marked by a PVC frame in front of him. Like magic, the soil starts to wriggle to life as worms shoot up to the surface.

But this is not magic; it’s an infestation. These thrashing invertebrates are the invasive jumping worm. They’re known to ruin soil quality by removing vital nutrients, leaving the soil looking more like coffee grounds than an ideal place to grow a tomato plant.

Gardeners, Friends of the Arboretum, Boy Scouts and nature lovers united under one title to help Herrick collect data on the worms: citizen scientists. The group of almost 30 people, ranging from elementary schoolers to retirees, volunteered on a Sunday afternoon to learn about the invasive species, the threat they pose to soil quality and most importantly, how to document their presence around the Madison Metro Area.

After a training session at the Arboretum, teams of volunteers were sent out to sample 120 urban sites. Five years ago, the first version of the survey sampled these same sites.

Now, Herrick, ecologist and research project manager at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum, will be able to use the data they collect to see how the jumping worm population has changed over time.

Herrick, who is also studying jumping worms as a PhD candidate in the Nelson Institute for Environment, shows volunteers how they will conduct the survey. Using PVC frames, soil moisture readers, and a mixture of mustard and water, the volunteers will help collect worms from the same sites around Madison that were surveyed 5 years ago. Elise Mahon

On this particular afternoon, Herrick gathered the citizen scientists around a patch of grass across from the Arboretum Visitor Center to demonstrate how to conduct the survey.

Teams were instructed to pick an area to lay down their PVC frames by first scanning the site for signs of coffee-ground soil. Then, they were shown how to use a special tool to measure soil moisture and pour a gallon of mustard infused water into the frames.

“It won’t take long,” Herrick explained. “The jumping worms live right below the surface so if they’re there, they’ll pop out in a few seconds.”

After recording the number of worms that surfaced and placing them into a small, labeled container along with a bit of soil, the volunteers repeated the process twice more around the flower bed. Then they repeated the whole process, taking another three frames of sample from the lawn.

Gail Moede Rogall (left), Tam Mayeshiba, Pat Mayeshiba, and Ben Mayeshiba gather to discuss the most efficient way to survey their assigned sites around Madison. Mayeshiba’s son Ben and Moede Rogall’s son Bjorn (not pictured) are both Boy Scouts in Troop 104. Elise Mahon

With a demonstration complete and cars loaded up with supplies, survey teams mapped out the order they’d conduct their sampling at assigned sites across the Madison area and set off.

Herrick and Laurie Yahr pour a mix of mustard and water to irritate the worms and encourage them to surface. Elise Mahon

The invasive worms live just below the surface of the soil, so it only takes a few seconds for them to shoot up out of the ground, writhing and jumping. Herrick reaches for an earth worm to put in a small Tupperware container for official identification and analysis later. Elise Mahon

Since the presence of jumping worms was first confirmed in the state in 2013 at the UW–Madison Arboretum, public interest has only grown. While there are no terrestrial earthworms native to glaciated areas of North America, jumping worms pose a particular problem because of the speed at which they change the soil.

All earth worms expel their digestive waste back into the soil, depositing vital nutrients that plants need to grow. Worms like nightcrawlers burrow into soil, depositing nutrients at deeper soil layers along the way.

Jumping worms, however, don’t burrow but stay just below the surface. They expel their digestive waste, and all those vital nutrients, in the form of little capsules called “castings” that leave the top layer of soil loose and porous like coffee grounds.

“Earthworms are ecological engineers,” explains Herrick, who is also a PhD candidate at the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies.

What happens in soil can have a cascading effect that impacts plants and animals further up the food chain.

With jumping worms, loose granular topsoil can be washed away more easily, taking nutrients away with it. Less soil and less nutrients make it more difficult for new growth to successfully take root. Over time, that could limit the types of plants that make up forests and what can be grown in backyards.

Herrick receives a text from one of the survey volunteers asking for verification on soil characteristics. Invasive jumping worms produce excrement in the form of castings that turn soil into a porous, coffee ground-like texture that washes away easily and can make it difficult for some plants to establish themselves. Elise Mahon

Herrick can’t be with every team at every sample site, but they all have his contact information so he can help answer any questions they may have while out in the field. Before driving to a new site, he helped one team determine if soil was showing signs of the coffee ground texture.

“This survey is only possible because we have all of these volunteers,” Herrick says. “The participants are eager to learn and hopefully this experience will propel them to share with their neighbors and friends the importance of learning about this invasive species.”

He also added that it’s important to get as much data as possible in a short amount of time because earthworm presence and abundance can be affected quickly by changes in soil moisture and temperature. In a single afternoon, the volunteers were able to sample about half of the 120 urban sites in the survey. Herrick and his team sampled the rest of the sites within the next few days.

Yahr holds out the tupperware collection container for Herrick to deposit jumping worm samples into. The survey this year is collecting all worms that surface in the sampling frames. Later, when Herrick identifies the species of each worm collected, they hope the data will show how the jumping worms may be affecting other earth worm populations. Elise Mahon

Herrick holds a lively jumping worm collected from an infested flower bed in a Madison backyard. Elise Mahon

In the first survey, jumping worms were found in forests, open spaces such as city parks, residential gardens and lawns. They are most often found in artificial green spaces curated by humans through landscaping and gardening with materials like mulch.

“We’re still at the forefront of this invasion, so it’s a really cool opportunity to track [it] from the inception and maybe keep this isolated or contained,” Herrick says.

So far, the worms don’t seem to have spread to urban grasslands. With data from the most recent sampling, Herrick says that he and other researchers can determine which land cover types jumping worms are found in the most abundance and compare those findings to the survey from five years ago.

“These worms are spreading quickly, but at least in this survey, they appear to not have spread quickly outside of these tight urban areas,” Herrick says.

This years’ survey also includes land cover data from 71 sites in rural areas of Dane County, to see if the worms are found in the same or different land cover types compared to the Madison metro area. Preliminary data suggests that only four of the rural sites they sampled had jumping worms, two in forests and two in mulch gardens.

Herrick’s team also found jumping worms at three out of six municipal yard waste dump sites that sit at the edge of urban and rural spaces. They believe these could be a gateway that allow jumping worms to slowly creep out of urban spaces and into rural ones.

Humans may also be enabling their spread through the movement of horticultural materials like mulch. It’s a possibility the team will be considering and watching out for in future surveys.

Herrick and Yahr pick up their supplies from their last sampling site before heading back to the Arboretum to reconvene with the other survey teams. At the end of the survey day, volunteers helped collect worms and data from about 83 sites around Madison. Elise Mahon

Herrick, who has worked as an ecologist for 15 years at the Arboretum, is fascinated by the endless questions and potential implications this invasion poses. The average person may not notice a new kind of worm in their backyard, but that worm could cause small disturbances that travel up the food chain, leading to larger issues in the ecosystem.

That’s why Herrick is so excited to have a community of passionate volunteers helping collect data to monitor the invasion as it develops.

“You don’t know what you have until you actually go out and monitor the environment,” Herrick said. “So, for us to be able to say what sorts of habitats this invasive species is found in can really help land managers control their spread.”

Tags: animal research, arboretum, ecology