UW Arboretum begins final upgrades to stormwater management infrastructure

A goldfinch perches on amid a sea of flowering prairie dock, purple gayfeather and rattlesnake master plants at the Curtis Prairie at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum. Photo: Jeff Miller

This spring, the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum and local municipalities will complete the final phase of improvements to stormwater management infrastructure that protects the Arboretum’s restored ecosystems and Lake Wingra from urban runoff.

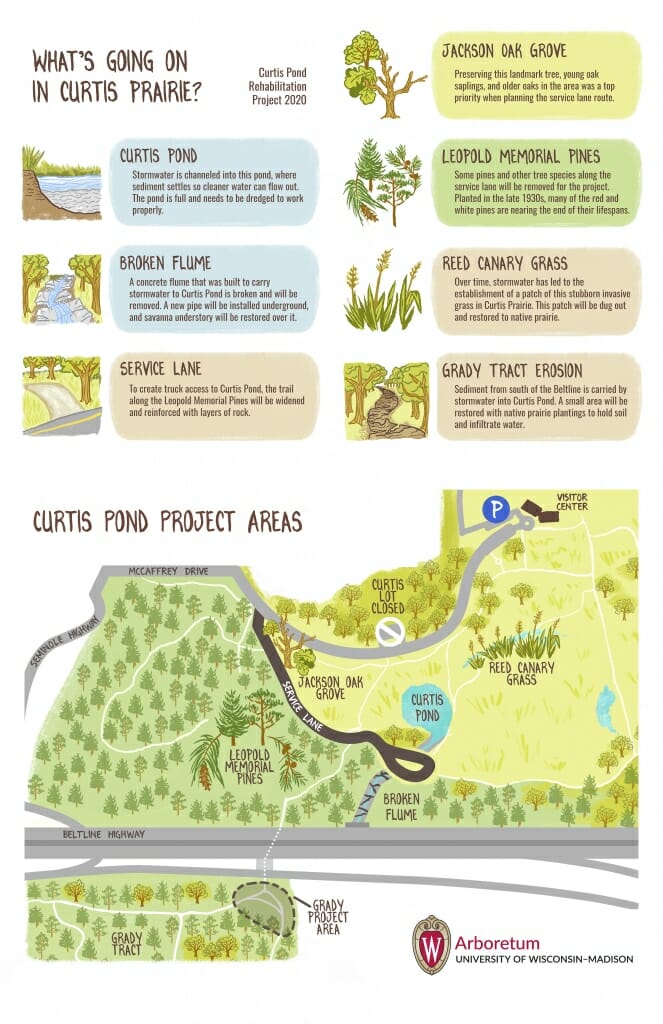

The final and most visible project will begin in early March at the edge of the Curtis Prairie, the oldest restored prairie in the world. A stormwater retention pond will be rehabilitated, a broken flume will be rebuilt, and invasive species will be removed and replaced with native plants.

The project will require removing select pine and other trees adjacent to the prairie to create a service lane for machinery, but Arboretum staff have erected barriers to protect the Curtis Prairie from damage during construction. Frequent construction traffic will travel along McCaffery Dr., and some trails will be closed, so visitors should follow all posted signs to ensure their own safety.

Following the project’s expected completion in May, Arboretum staff will restore the affected areas with native plants. Costs are shared between UW–Madison and the City and Town of Madison.

The retention pond slows down fast-moving stormwater from the nearby Beltline highway and residential neighborhoods laden with pollutants, road salt and nutrients, and allows this sediment to settle to the bottom. Water leaving the pond is cleaner and has fewer nutrients. Excessive nutrients promote the growth of invasive species.

“Without a pond we would have stormwater racing into the prairie with a high sediment load,” says Arboretum ecologist Brad Herrick, who is directing protection and restoration efforts during the project. “All those things are a recipe for invasive species getting established, reduction of native species, and erosion.”

The Arboretum helps manage and filter half a billion gallons of water from nearby communities each year. That is more than a quarter of the volume of Lake Wingra, where much of that water ultimately flows, and which empties into Lake Monona.

The Curtis Pond restoration is the culmination of years of other retention pond and wetland improvements to manage heavier stormwater volumes caused by increased urbanization and heavier precipitation linked to climate change.

“The past several summers of extremely heavy rainfalls have illustrated the importance of managing stormwater at the top of the watershed rather than in the Arboretum,” says David Liebl, a professor emeritus in the College of Engineering who led the committee that developed and implemented the Arboretum’s stormwater management plan beginning in 2006.

Ideally, rain would be able to infiltrate the ground where it falls. But impervious surfaces such as roofs, roads, sidewalks and driveways channel this water downhill. Liebl says that Madison has begun to increase the city’s ability to handle stormwater upstream, but the Arboretum will continue to manage large volumes of stormwater because it lies at the bottom of the Lake Wingra watershed.

During construction, a patch of invasive reed canary grass will be mechanically removed from Curtis Prairie. Reed canary grass thrives in nutrient-rich conditions supported by untreated stormwater. Herrick and other Arboretum staff will oversee re-seeding of native prairie plants to this area following construction, and improvements to Curtis Pond will help these native plants establish and outcompete weedy species.

“The end result will be an increase in plant diversity and a healthier prairie,” says Herrick.

For more information on the Curtis Pond restoration, visit the Arboretum’s project website: https://arboretum.wisc.edu/visit/curtis-pond-rehabilitation-project/