Anthony Shadid: A journalist’s life remembered, a legacy that lives on

In December 2010, foreign correspondent for the New York Times Anthony Shadid (center) spoke to a group of journalism students in a Vilas Hall classroom. Shadid is a UW–Madison alumnus and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner.

Photo: Bryce Richter

The world knew Anthony Shadid as a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who covered the strife-torn Middle East, often at considerable personal risk. The University of Wisconsin–Madison knew Shadid when he was just a young journalism student on deadline for the Daily Cardinal.

Shadid, 43, died Thursday, Feb. 16 of an apparent asthma attack while on assignment in Syria for the New York Times.

While stories and tributes immediately appeared worldwide, staff and students remembered Shadid for the legacy he leaves on campus. See this collection of Tweets, images and videos assembled by the College of Letters and Science.

The New York Times also collected messages from Twitter, where there was an outpouring of tribute and emotion.

On Friday morning, the front page of the Cardinal, the student paper where he once served as editor, featured a picture of a young Shadid. He first appeared at the paper on a summer day in the late 1980s carrying an army rucksack containing what appeared to be everything he owned, editor Kayla Johnson writes.

The news hit the Cardinal’s staff hard as they worked to pay homage to the man they consider their hero.

“He’s someone who was the definition of a journalist,” 20-year-old Johnson says. “He’s doing what you imagine yourself doing.”

Shadid once said that some of his favorite years in journalism were spent at the Cardinal.

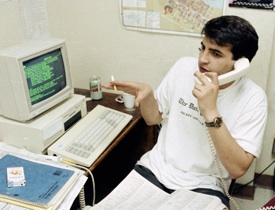

Shadid works at the Daily Cardinal in the 1980s. (Photo by Peter Barreras)

“There weren’t a lot of rules,” Shadid said. “You kind of made the rules as you went along but you learned how to do journalism – that day-to-day challenge of putting out a newspaper every morning.”

Born in Oklahoma City, Okla., Shadid came to Madison and graduated in 1990 with a bachelor’s degree in political science and journalism.

“In a lot of ways, I think I owe everything, at least in my early part of my career, to the university,” Shadid once said.

Jon Pevehouse, a professor of political science and public affairs, remembers how engaged Shadid was with international studies students while he visited campus.

“He connected so well with the students,” Pevehouse says. “He just clearly reveled in what he did.”

Pevehouse calls Shadid’s reporting from the Middle East remarkable.

“Whether being beaten by Qadaffi’s thugs or hopping from Tunisia to Egypt during the revolutions of 2011, Shadid was always in the middle of the action, reporting the news from the street as well as news from official sources,” Pevehouse says.

He also learned Arabic at UW, a language that would serve him well in his work. Shadid had long been interested in the Middle East, first because of his Lebanese-American heritage and later because of what he saw there firsthand, his obituary in the New York Times says.

Shadid spent most of his professional life covering the Middle East, as a reporter first with The Associated Press; then The Boston Globe; then with The Washington Post, for which he won Pulitzer Prizes in 2004 and 2010; and afterward with The New York Times.

“The question: ‘Where is Shadid now anyway?’ is not uncommon in the office,” Johnson writes. “Whatever the answer, reporters’ eyes glaze over as they imagine themselves interviewing protesters in the middle of the night in Tahir Square before rushing to Libya while the Arab spring catches fire.”

Last March, Shadid was kidnapped in Libya along with three other New York Times’ journalists, including UW–Madison graduate Lynsey Addario, an internationally acclaimed photographer. They were held for six days and beaten before being released.

Katy Culver, a professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication, was on campus in the 1980s at the same time as Shadid but didn’t meet him until spring 2002 when she nominated him for the school’s Nafziger Award for achievement within 10 years of graduation.

“He was shot in Ramallah shortly before he came to campus to accept that award,” Culver says. “When he got here, he apologized for worrying me by getting shot.”

Shadid’s intellect and lyrical writing infused all his work and set him apart, Culver says.

“In a lot of ways, I think I owe everything, at least in my early part of my career, to the university.”

Anthony Shadid

“No one who knew or read him could miss his dedication to deepening our understanding of the Middle East,” Culver says. “But I believe his humility defined him as a journalist. It was unmistakable. He saw each person and each moment as larger than himself.”

In December 2010, Shadid came back to UW as the keynote speaker for the Center for Journalism Ethics. He gave a lecture entitled “The Truths We Tell: Reporting on Faith, War and the Fate of Iraq.” A video of that lecture can be viewed here.

This article in On Wisconsin magazine also focues on that visit to campus.

“How do you deal with fear?” asked journalism professor Stephen J.A. Ward, director of the Center for Journalism Ethics, during a public lecture on the Iraq war.

“I think there are stories worth getting hurt for,” Shadid said. “I didn’t enjoy getting shot in the back, but I think that story was worth telling.”

Shadid was also the first speaker in the UW–Madison Language Institute’s Language for Life Series in which they bring back an alum who talks about how they use language in their career.

“He talked about how his proficiency in Arabic was critical to his reporting,” says Dianna Murphy, associate director of the Language Institute. “It’s hard to imagine how a reporter could do that kind of in-depth reporting that he did without knowing the language.”

Dustin Cowell, a professor of Arabic and chair of the Department of African Languages and Literature, had Shadid as a student in his first-year Arabic class. He remembers Shadid’s enthusiasm and how he encouraged other students to embrace the Arabic only rule in the classroom.

“He was just one of those fun loving students who gave spirit to the class and made it a fun place to be,” Cowell says.

But he was also very dedicated to his studies. Cowell still has Shadid’s final exam on which he received an A-plus.

“He’s really a fine example of what you can do with a foreign language in your professional life,” Cowell says. “It gives you a different way of looking at the world and makes it easier to draw people to you when you show an interest in their language. It sort of builds bridges immediately.”

Erin Banco, 22, graduated from UW in 2011 with degrees in journalism and African literature and language. Currently, she’s a freelance journalist in Cairo and student studying the intensive Arabic language program at the American University in Cairo. Shadid was her mentor.

“Anthony was my journalistic idol,” Banco says. “He represented everything I wanted to be and I aspire to be like him.”

She’d been in contact with him just last week about meeting up the next time he was in Cairo. Banco, like Shadid, was once campus editor of the Daily Cardinal.

“His language fluidity and storytelling abilities were unparalleled, in my opinion,” Banco says. “But beyond his writing abilities, Anthony possessed a certain journalistic charm. He was fearless, for one. But more importantly, Anthony was wildly passionate about what he did. And it showed.”

In 2002, the journalism school awarded him the Ralph O. Nafziger Award, honoring achievements by young alumni. In 2005, the Wisconsin Alumni Association honored him with its Distinguished Alumni Award, and a video of his acceptance speech can be viewed here.

He was also a recipient of a fellowship in 1991-92 at the American University in Cairo, where he studied Arabic. He specialized in the Middle East in graduate work at Columbia University in New York in 1993-94.

Shadid, an avid Green Bay Packers fan, was the author of three books, “Legacy of the Prophet: Despots, Democrats and the New Politics of Islam” (2001); “Night Draws Near: Iraq’s People in the Shadow of America’s War” (2005); and “House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family, and a Lost Middle East,” to be published next month by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

When he died, Shadid had been reporting inside Syria for a week, gathering information on the Free Syrian Army and other armed elements of the resistance to the government of President Bashar al-Assad, the New York Times reported.

“Anthony Shadid died in the midst of performing his life’s work as a journalist of the highest quality and integrity — thoughtful, serious, important work that I know we are all so very proud of, and so very thankful for,” says Greg Downey, professor and director of the School of Journalism & Mass Communication. “We will miss him terribly.”

Johnson had hoped to interview Shadid as the Daily Cardinal celebrates its 120th anniversary in April. She says it’s a honor to get her start in journalism the same place he did.

“When everyone asks what are you going to do with a journalism degree, I point to the front page of the New York Times and there’s Anthony Shadid’s byline,” Johnson says. “I say that’s what I’m going to do.”

Survivors include his second wife, the journalist Nada Bakri; their son, Malik; a daughter, Laila, from his first marriage; his parents; a sister, Shannon, of Denver; and a brother, Damon, of Seattle.

There are campus plans for a scholarship and possibly an award bearing his name.

“Anthony gave us all the gift of insight and humanity,” Culver says. “I had looked forward to many more years of his journalism and his friendship, but I will be forever grateful for the ones he already shared. His death is a tragedy, but his life is an inspiration.”

Video: Five questions with Anthony Shadid