UW funds will improve app to help vets at ‘Dryhootch’ coffeehouses

MILWAUKEE — It’s a quiet March afternoon on Brady Street in Milwaukee, and a few folks are enjoying first-class java at Dryhootch Coffeehouse.

Andy Rosario, a Vietnam Marine veteran, is playing guitar. Then Tom Pieper, who lucked out in the draft lottery, brings out his guitar, and they talk quietly as they start to tackle a Beatles song.

“When you play music, the other stuff just kind of goes away,” says Rosario.

Dryhootch is a nonprofit, alcohol- and drug-free hootch (Vietnam-era slang for shelter) dedicated to the physical and mental health of U.S. veterans.

The coffeehouse — the brainchild of Vietnam vet Robert Curry — opened 10 years ago. The organization has a second location near the Milwaukee VA Medical Center on National Avenue, and a coffeehouse near the veterans hospital in Madison. There are plans to open an apartment building and coffeehouse on Madison’s East Side, and for another in Atlanta.

Dryhootch is a shoestring affair that has received financial help and other assistance from government, foundations and institutions. In January, it received a $50,000 grant from the Wisconsin Partnership Program at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. The grant will fund refinements of a prototype smartphone app built to connect vets statewide and beyond to Dryhootch.

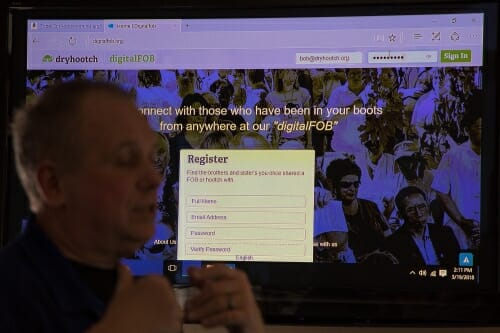

Robert Curry plans to use a new grant from the UW–Madison School of Medicine and Public Health to improve Dryhootch FOB (“Forward Operating Base”), an app that connects vets to vets, and to assistance in their communities. Photo: Hyunsoo Léo Kim

Working with many community partners, Dryhootch’s broad mission is to heal the emotional or physical trauma of service, and to reintegrate veterans into society. Reaching that goal can mean overcoming obstacles to employment, education or housing.

But the starting point may simply be a safe place to hang out, mingle and reminisce. To tell a joke. Or to sit quietly.

There is one role that Dryhootch rejects, however. “When a vet walks in here, we are not making judgments,” Curry says. “Outside, if you reveal something about your service, you may be judged as less than human. But you can tell another vet.”

In an interview upstairs, Curry wrestles with the long story of how he started Dryhootch. When Curry returned from Vietnam in 1971, protestors showered him with bloody chicken guts, rotten eggs and vulgarity, so he stuffed his army uniform in a trashcan.

He, like many other Vietnam-era vets, also tried to “stuff” the memory of his service and the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder it had caused. “But when the 1990 Gulf War hit, the symptoms came roaring back, with flashbacks and drinking,” he says. “I started overeating to force myself back to sleep from the nightmares, and got up to 330 pounds.”

In 2011, he drank himself into a stupor and reached rock bottom in a hospital room, as a police officer told him, “The gentleman you hit died.”

Curry was charged with homicide by intoxication — and later found not guilty by reason of insanity due to a rampant case of PTSD. As he emerged from state mental institutions, fellow Vietnam vets helped him confront the classic PTSD symptoms of exaggerated arousal and flashbacks.

“My daughter called several veterans for help. Most did not know me, only that I was a fellow brother,” Curry says. “These vets were like the fire guys who go into a building when everybody else is leaving. My drinking buddies ran the other way.”

Later, he visited a Veterans of Foreign Wars post with his sponsor from Alcoholics Anonymous. “When I walked out, I thought, this is pretty cool. But can we talk, get into this dark humor without the booze?”

Thus was born Dryhootch: named for the shelters used by civilians and soldiers in Vietnam, and created as a drop-in coffeehouse where vets can talk it over — or not. Where they can enjoy each other’s company, get a great cup of coffee and, if they choose, explore the many sources of assistance that Dryhootch has identified in the community.

It’s a safe place with one sure-fire icebreaker: “Where did you serve?”

Though veterans have high rates of alcoholism, depression and homelessness, they should not be stereotyped, Curry says; many are doing just fine and they, too, are welcome at Dryhootch, as are non-vets. Among those who do need help, Curry says, the best medicine is often the same one that put him back on his feet: peer support. Veterans tend to trust other veterans more than, for example, the VA. “Non-veterans who ask ‘What was it like?’ either can’t understand or don’t really want to hear the answer,” he says.

Veterans, especially those who have been trained to use a system developed by Dryhootch, the VA, Marquette University, the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and the Medical College of Wisconsin, are better positioned to help peers with the myriad issues that afflict veterans in inordinate numbers: thoughts of suicide, lack of housing, family breakups and joblessness, Curry says.

Marine Corps veteran Robert Garza handles social media for Dryhootch, and uses his experience at UW–Milwaukee to advise fellow veterans applying for veterans’ education benefits. To help a close friend, “I walked him through everything — how to apply for a VA grant, apply to school, get the paperwork and housing grants submitted.” Photo: Hyunsoo Léo Kim

When Dryhootch applied to the Wisconsin Partnership Program for funding to advance its smartphone and web app, the peer-to-peer aspect and innovative approach stood out, says program officer Courtney Saxler at the School of Medicine and Public Health. “Bob is a vet, and works with vets day-in and day-out. Our goal is to improve health equity in Wisconsin, and veterans face significant health disparities, in particular access to mental health services.

“The community that is impacted by the inequity, and will benefit most from the intervention, must be part of the planning, and Dryhootch fits that perfectly. We believe that those closest to the problem are closest to the solution.”

Solutions at Dryhootch come from many directions, and some are pretty basic. Some vets need better clothes for job interviews, so Milwaukee’s Equitable Bank asks its customers to donate suits, then funds dry cleaning. “We’re not saying dry cleaning would cure PTSD, but a suit can lead to a job, and a lot of good things can come from that,” says Curry.

Dryhootch located Zack Marsh, a barber, who offers a free haircut to vets. “If you don’t have a dime, maybe a haircut will give you a little bit of dignity and a chance for a job,” Curry says.

The guitars in the coffee shop echoed the ’60s — though the long hair was short, and gray at best. But music has a role, Curry says. “Maybe for your mental health you need to play music, take up an art form, do yoga or engage in physical fitness. Maybe acupuncture is what you need. Finding something outside the ‘medical’ realm means maybe you won’t have to visit the VA to get some pills to feel better.”

There are other possibilities along these lines, Curry adds. “Early on, a vet came up and said, ‘We are always told at the VA to do art, or writing, some holistic thing. But I work on cars.’ We figure, if you get people working on a car, they will talk stuff over, so we’re thinking about putting something industrial in our Madison facility.

“We’re just trying to give a reason for people to get together and talk about their common journey.”

Dryhootch Coffeehouse is located at 1030 E. Brady Street in Milwaukee.

###

—David Tenenbaum, 608-265-8549, djtenenb@wisc.edu