Tried-and-true tips for staying warm and safe while biking through winter

When UW’s bicycle and pedestrian coordinator Chuck Strawser moved from Atlanta to Madison, it didn’t take long for him to fully comprehend just how out of sync his expectations of Wisconsin’s winters were with what Wisconsin’s winters were actually like.

“Winter hit and my eyelids froze shut,” he said.

Now, 21 winters later, Strawser is a veritable master of winter biking. Riding a specially designed “fat bike” with four inch wide studded tires designed for ice and outfitted in clothes that can get him through even the most bitterly cold days, he has figured out the best ways to stay safe and warm while riding through the winter.

But you don’t need a specialized bike or expensive clothes to bike through the winter, he says. Most people can bike through winter without having to spend much money at all. Here are some tips from Strawser on how to do it.

A cyclist makes their way along the snow-covered Howard Temin Lakeshore Path during winter at the University of Wisconsin–Madison on Jan. 26, 2016. Photo: Bryce Richter

Cut down on wind wherever possible

Wisconsin winters can both painfully cold and unpredictable, often dropping in temperature by 40 degrees over the course of a day. An important component of this unpredictability is the wind.

“That’s a big problem with winter here. Sometimes it’s 20 degrees, and if it was a calm day, it’s fine, it’s beautiful,” Strawser said.

Other days, however, 20 degrees can feel like -10 because of wind chill. On these days, bicyclists need to prevent the wind from hitting their extremities, especially the fingers, face, ears, and feet.

For your hands, you can buy “handlebar mitts,” sometimes called “pogies,” to protect your exposed hands from the wind. These are often made of neoprene, which also acts as an insulator. If you’re strapped for money, Strawser says you can cut a milk jug in half and zip tie it to the handlebars. While these won’t insulate your hands, they will cut down on the wind just as well as more expensive, store-bought handlebar covers will.

Similar products exist for the feet. These attach to the pedals and shield the toes, which are often one of the first areas of the body to turn ice cold if not properly insulated. A budget, DIY option is simply wrapping your feet in two bread bags.

Also: if you can grow it, facial hair helps, Strawser says.

A bicyclist pedals in the bike lane along University Avenue against a backdrop of car lights and rush hour-traffic traveling through the heart of the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus at nightfall. Photo: Jeff Miller

Wear a snowboard/ski helmet instead of a bike helmet

Snowboard or ski helmets have basically the same safety standards as bicycle helmets and are also warmer, Strawser says.

They typically have padding to keep your ears warm and a place to put your goggles. To further cut down on wind chill, Strawser places a small piece of duct tape where the bridge of his nose is exposed. Even something as small as a piece of tape can be the difference between staying warm and freezing in sub-zero temperatures.

As for ski goggles, Strawser recommends bicyclists get a pair. These also have padding around the eyes for insulation and eliminate the tear-inducing pain that comes with having your eyeballs exposed to the cold, whipping air. For those who wear glasses, OTG (“over the glasses”) goggles exist. These will prevent you from having your eyelids frozen shut like Strawser’s did 21 years ago.

A man rides his bicycle along McCaffrey Drive through the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum. Photo: Jeff Miller

Dress in layers, wearing wool wherever possible, to stay warm and wick away sweat

From head to toe, Strawser doesn’t like to wear clothing that restricts his movement or that he has to take off when he gets to work.

“Basically I ride to work in what I’m going to work in,” Strawser says.

Working from the top down, he wears either a “neck gaiter” or, if it’s really cold, a balaclava. The neck gaiter is nice because, unlike long scarves that can potentially fall and get tangled up in the gears or spokes of the bike, it rests on the neck and can be pulled up to cover the bottom half of the face and ears.

For the upper body, Strawser dresses in layers. The bottom layer is usually a thin wool t-shirt. His is roughly 18 microns thick – basically as thin as a piece of wool clothing can get. If he needs to dress up for work, he’ll usually wear an oxford button up over top of it.

The advantage of wool over cotton and synthetic fibers is that wool both keeps you warm and wicks away sweat, Strawser says. If you sweat in cotton, it will freeze and make you even colder than you were in the first place. If you sweat in some synthetic fibers, you’ll stink for the rest of the day.

On top of the wool t-shirt he often wears a turtleneck. On moderately cold days, he’ll top it all off with a reflective, waterproof running shell. On the coldest of winter days, Strawser replaces his running shell with a puffy jacket or long snowboard parka.

When Strawser first started riding through winter, he wore long underwear. While these are great for keeping you warm outside, they keep you too warm when you get indoors. If you don’t want your underwear giving you a heat stroke, Strawser recommends opting for flannel lined pants. Retailers sell all kinds of different pants, including jeans, with flannel linings, and they will keep your legs warm enough outdoors and cool enough indoors.

Finally: the feet. For socks, wool is the way to go. On the coldest of days, maybe double up on socks – it’s better safe than sorry. For shoes, Strawser wears waterproof hiking boots that don’t look out of place in the typical office or classroom on campus.

The key to all of it is to wear layers so that you can adjust to the temperatures outdoors from day-to-day and feel comfortable indoors.

A pedestrian is seen in an overhead view strolling along a snow-covered walkway past parked bikes outside UW–Madison’s Helen C. White Hall during winter/ Photo: Jeff Miller

Studded tires help, but you can get by without them most days

Because the roads are typically cleared before the first class of the day, most bikes should stay upright unless it’s blizzarding or icy with the tires they already have. Remember to use both the front and the rear brakes at the same time, though, so you don’t take a spill.

But if you want to ride when it’s icy, and can afford to do so, buy studded tires. The studs, typically made of some type of hard, sharpened material, are crucial for gaining traction and staying upright on snow and ice. Fat bikes with studded tires can even ride across a frozen Lake Mendota, Strawser says.

If you can only afford one studded tire, though, put it on the front and not the rear. One is better than nothing.

Besides studded tires, though, most bikes do not need to be outfitted specifically for winter, Strawser says. However, it helps if you install fenders so that the bike doesn’t kick up slush up onto your back.

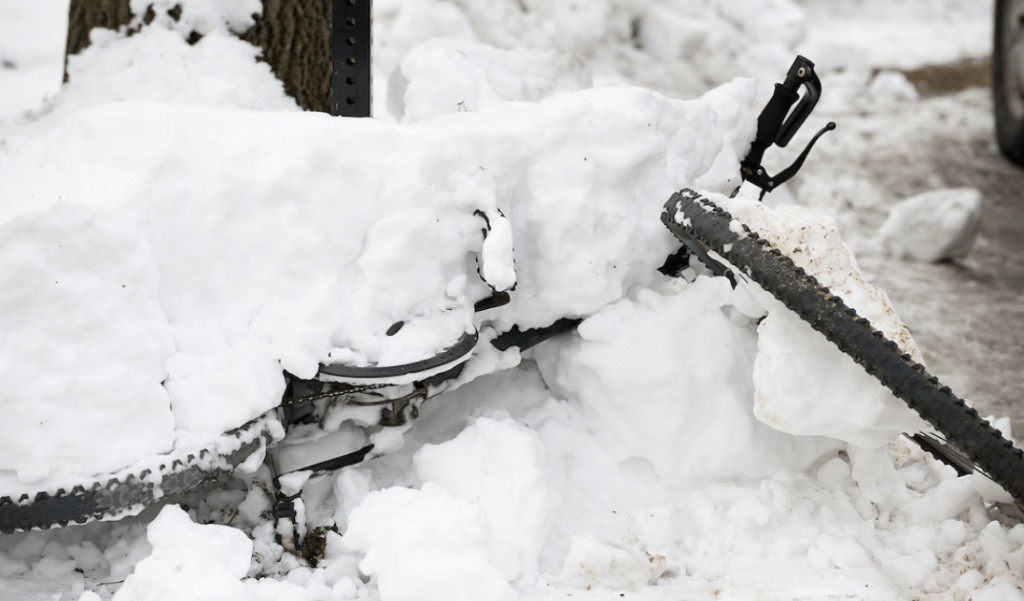

A bicycle buried in a pile of plowed snow is pictured in the Lot 3 parking area along Lake Street at the University of Wisconsin–Madison during winter. Photo: Jeff Miller

Road salt is hard on bikes, so make sure you keep up with maintenance

The city of Madison typically uses salt to melt the ice on the roads, which is good for safety but damaging for bikes.

“You need to think about that and anticipate either doing a lot of maintenance during or after winter if you want your bike to work the next winter,” Strawser says.

The chink in the chain, so to speak, is the bike chain itself. To get the salt off and lubricate the chain, Strawser recommends a petroleum base lubricant. Using a drip bottle, place a drop of lubricant on each link of the chain.

Don’t spray the chain and don’t use WD-40 unless your chain is so far-gone and rusted that it won’t go through the gear changer. Spraying the chain can potentially send lubricant onto the brake and WD-40, which is mostly composed of solvent formulated to loosen rusted lug nuts on farm equipment, can dissolve the grease in the ball bearings located at points throughout the bike.

Strawser admits he doesn’t take keep up on maintenance with his bike. But then again he doesn’t really have to: he has a belt drive. A belt drive is cleaner than a chain and can better withstand winter conditions and is worth it if you can afford it.

A bicyclist pedals on a bike lane at an intersection along University Avenue against a backdrop of car lights and rush-hour traffic traveling through the heart of the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus at nightfall. Photo: Jeff Miller

Be visible, predictable, alert, and assertive

These four elements of staying safe as a bicyclist apply all year long but are especially important during the slippery months of winter.

First, be visible. Wisconsin law requires a front light and rear reflector on bikes, so make sure you have those. For both, it’s less about you seeing other things as it is others seeing you. A blinking front light is a great way to make sure oncoming cars see you.

Wear as much reflective clothing as possible. Strawser rears reflective ankle straps and his boots are lined with reflective material. His waterproof shell is bright red. Peer-reviewed research suggest that the human brain responds better to the outline of the human form than reflective shapes, Strawser says, so a brightly covered jacket is better than a jacket with a reflective triangle on the back of it, for instance.

“You’re better off making your body look like a human body than making your body look like a road cone,” Strawser says.

Second, be predictable. Wisconsin law defines bicycles as motor vehicles, meaning that all of the same laws that apply to motor vehicles apply to bicycles. So, it should go without saying, follow the rules of the road.

However, Strawser realizes that individuals in every group – motorists, pedestrians, even public transit workers – break these rules. So bicyclists need to be as predictable as all other users on the road.

The third and fourth keys go together: be alert and be assertive.

Being assertive doesn’t mean being a jerk, but it can actually be more dangerous if you are a passive biker who is constantly waving on cars when you have the right of way. When Strawser goes through intersections, he keeps pedalling even if he sees someone preparing to make a turn. This shows the driver that you know you have the right of way and are intent on using these rights.

Unfortunately, some roads in Madison are so narrow that a car cannot comfortably pass you without switching lanes. In this case, it’s safer to ride in the middle of the lane – not just for you but for other drivers – as it is to try to squeeze by along the curb. Although Wisconsin law requires bikers ride as close to the curb as is “practical,” it’s more dangerous to encourage drivers to squeeze past you by riding inches away from a curb on a narrow road than it is to clearly indicate to drivers that they will have to switch lanes and pass you.

For more winter biking tips, check out UW Transportation Services’ list. The University Bicycle Resource Center (UBRC), located in the northeast corner of the ground level of the Helen C. White parking garage, provides bicyclists with a variety of services, including tune-ups, repairs, and free, monthly bicycling events and clinics. Learn more here.