NAS panel takes stock of U.S. science literacy

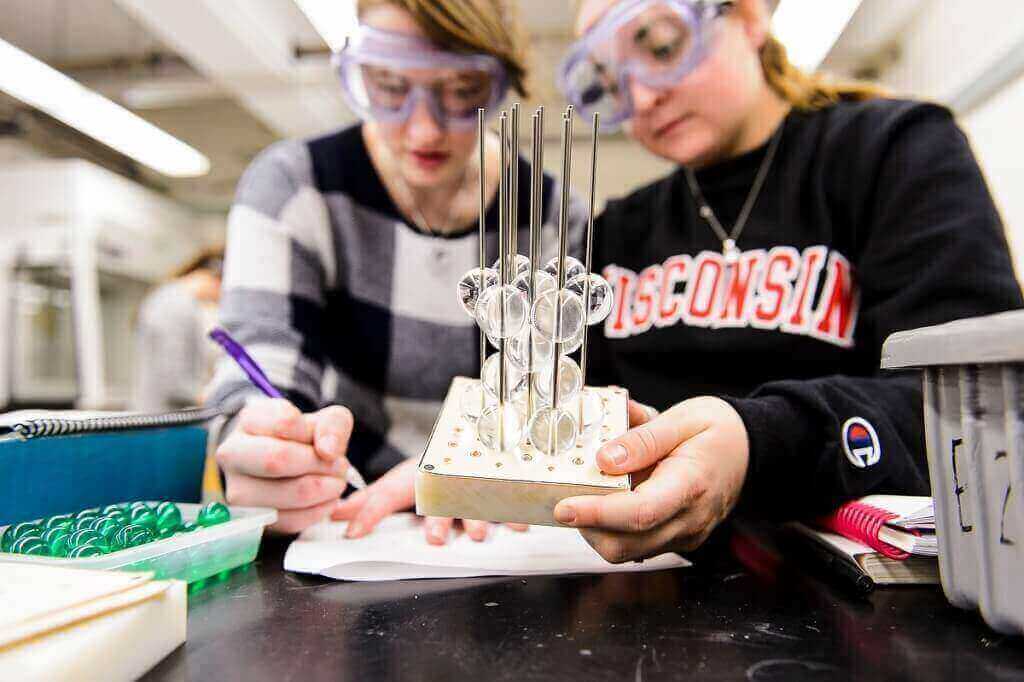

Undergraduates Michelle Locke, left, and Bailey Spiegelberg conduct lab experiments and build three-dimensional molecular models of various solid-state materials during a UW–Madison chemistry class. Photo: Jeff Miller

What does it mean to be science literate? How science literate is the American public? How do we stack up against other countries? What are the civic implications of a public with limited knowledge of science and how it works? How is science literacy measured?

These and other questions are under the microscope of a 12-member National Academy of Sciences (NAS) panel — including University of Wisconsin–Madison Life Sciences Communication Professor Dominique Brossard and School of Education Professor Noah Feinstein — charged with sorting through the existing data on American science and health literacy and exploring the association between knowledge of science and public perception of and support for science.

“The goal is to try and get the big picture,” says Brossard, a noted social scientist and expert on science communication. “We’re not looking at any single area of science and it is a consensus report, meaning we all have to agree, assuring multiple perspectives will be reflected in the final product.”

The committee — composed of educators, scientists, physicians and social scientists — will take a hard look at the existing data on the state of U.S. science literacy, the questions asked, and the methods used to measure what Americans know and don’t know about science and how that knowledge has changed over time. Critically for science, the panel will explore whether a lack of science literacy is associated with decreased public support for science or research.

Historically, policymakers and leaders in the scientific community have fretted over a perceived lack of knowledge among Americans about science and how it works. A prevailing fear is that an American public unequipped to come to terms with modern science will ultimately have serious economic, security and civic consequences, especially when it comes to addressing complex and nuanced issues like climate change, antibiotic resistance, emerging diseases, environment and energy choices.

“There is such a thing as practical science literacy. What are the things we need to know to help manage everyday life and make decisions in the best interest of ourselves and our families?”

Dominique Brossard

While the prevailing wisdom, inspired by past studies, is that Americans don’t stack up well in terms of understanding science, Brossard is not so convinced. Much depends on what kinds of questions are asked, how they are asked, and how the data is analyzed.

It is very easy, she argues, to do bad social science and past studies may have measured the wrong things or otherwise created a perception about the state of U.S. science literacy that may or may not be true.

“How do you conceptualize scientific literacy? What do people need to know? Some argue that scientific literacy may be as simple as an understanding of how science works, the nature of science,” Brossard explains. “For others it may be a kind of ‘civic science literacy,’ where people have enough knowledge to be informed and make good decisions in a civics context.”

Science literacy, Brossard adds, might also mean having enough knowledge to make good personal decisions. For example, knowing that there is a growing problem with bacteria becoming resistant to available antibiotics might better inform people about when such medicines are helpful and when they might contribute to a growing problem.

“There is such a thing as practical science literacy,” says Brossard. “What are the things we need to know to help manage everyday life and make decisions in the best interest of ourselves and our families?”

The committee’s report is expected in early- to mid-2017.

Tags: communications, science