Still on stage after 40 years: Wisconsin firm grows beyond theater lighting

In a spotless, 10-acre factory in Mazomanie, Wisconsin, Loyal Burkhart II assembles gears for hoists that will raise screens and backdrops above a theater stage somewhere in the world.

The hoists being tested on the floor nearby are bound for a theater in Israel.

Stage rigging is a newish line of business for Electronic Theatre Controls, which was born in 1974. Way back then, microprocessors — still called “computers on a chip” — were just beginning to revolutionize industry, culture and commerce.

The company’s four founders, all UW–Madison undergraduates, made an audacious promise: They would base a control for stage lighting on solid-state technology. The control system would be smaller, more efficient and programmable.

The gamble paid off. Globally, ETC now has more than 1,200 employees, including 650 at its headquarters outside Middleton and 200 in Mazomanie. Aside from a Texas subsidiary that makes moving lights for events, essentially all of its sales volume is designed and produced in Dane County.

And ETC maintains ties to UW–Madison, including hiring many students (several of whom go on to become full-time employees) in a summer program and tapping the expertise of the Manufacturing Systems Engineering program and UW Center for Quick Response Manufacturing.

The company traces its roots to a charismatic professor of lighting who took his wide-eyed students to New York to install his lighting designs on Broadway and in other theaters.

The UW–Madison undergrads who started ETC invented a solid-state stage-lighting control that was small, efficient and programmable.

ETC donated a full range of spotlights and controls to Frederic March Play Circle in UW–Madison’s renovated Memorial Union, in exchange for the right to use the theater as a test site.

After ETC was spawned by theater student Fred Foster, French major James Bradley, and physics majors Bill Foster and Gary Bewick, it survived a period of standard startup turmoil before receiving injections of business — and credibility — in 1979 and 1982, when ETC quickly moved from obscurity to the big leagues with two contracts for lighting controls at Disney theme parks.

Since then, the company’s original focus has diffused from those solid-state lighting controls to one-stop shopping for theaters wanting the best in fully integrated lighting, including controls, software and spotlights, of which ETC has built almost 4 million in Middleton.

Chad Weberg, a 22-year ETC veteran, heads rigging manufacturing at the firm’s Mazomanie plant. The basic design for the rigging came from outside, he admits, but “When we buy an idea, we always find some way to improve it.” Photo by David Tenenbaum

The company’s credits include lighting systems at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center in New York, and the Hollywood Bowl. Its equipment also illuminates Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre and Disney theme parks worldwide.

Today, ETC has offices in Hollywood, New York, Hong Kong, London and other entertainment capitals. Evidence of its expansion into architectural lighting appears in equipment on the tallest building in the world, Dubai’s Burj Khalifa.

When asked about the success of ETC, many observers point to longtime CEO Fred Foster. “Fred did not come at this from the business point of view, or a manufacturer’s point of view,” says Mark Stanley, a UW–Madison alum who is an associate professor of lighting design at Boston University. “He is first and foremost a theater practitioner, and that makes a huge difference in how he approaches making the products that we use.”

Powered by Foster’s down-to-earth knowledge of the needs of live performance (“When you have 2,000 butts in the seats, everything has to work perfectly,” he says), ETC has invented, improved, grown, acquired, and grown some more.

Forty almost-new shipping containers form nine “neighborhoods” in ETC’s second expansion at Middleton headquarters. These containers (notice openings for doors and windows) are scheduled for occupancy in September. Photo by David Tenenbaum

One of its more recent acquisitions was a compelling design for stage rigging — used to raise and lower backdrops, curtains and screens — that would be easy to install and control.

Rigging is manufactured in a 10-acre factory in Mazomanie. “When we bought the building in 2013, the area we occupied felt like a postage stamp,” says Foster. The building is quickly filling up as ETC moves more of the lighting manufacturing operations there.

To make room for administration, design and development at the Middleton headquarters, 40 shipping containers are nearly ready to house workers in research, development and marketing.

ETC’s growing activity at the western edge of Dane County brings access to new employees in Iowa and Richland counties, Foster says. “A lot of them are farmers. They have a tremendous work ethic, and a farmer can do anything.”

Back to the starting point

ETC has been around long enough to write a coda to some of its best “founding stories.” The reconstructed Wisconsin Union Theater, for example, opened in 2014 with a full array of ETC lights and controls. It was the “old” Union Theater, Foster cannot help observing, that he and his co-founders “blacked out” in 1977 while demonstrating their invention. The culprit turned out to be the new, digitally controlled switches, which placed an instantaneous load on a system built to supply thousands of amps of electricity. The old and suddenly obsolescent system ramped up slowly enough to avoid the sudden, breaker-tripping load. Fortunately for the posterity of a young spinoff, the show raised its curtain on schedule a day later — using the new solid-state lighting controls.

ETC’s equipment is in the Kennedy Center, Metropolitan Opera, Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, the Hollywood Bowl and Disney theme parks.

Today, Shannon Hall, as the Union Theater is now known, sports a full line of ETC equipment.

In 1996, the Metropolitan Opera in New York City installed its first ETC lighting console. That was the same house where, more than 20 years previously, Fred Foster fell in love with theater and live performance — especially the view from backstage or the lighting booth.

ETC began installing these lighting consoles at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in 1996 and has been upgrading them since then.

As the frantic pressures on a young company have abated, the major shareholders have been able to think long-term, a process that led to an employee stock ownership program in 2015. The ESOP conferred one-third of the company’s shares to its long-term employees. When asked to explain, Foster described what he’s learned over the years. “We were a flyspeck on the side of the industry. For decades, the bigs would laugh at us at trade shows, but one by one, they dissolved after they were sold from one conglomerate to another. They lost good people; it was like peeling off layers of skin — eventually only a skeleton was left.”

Corporations supposedly exist to maximize shareholder value, generally measured by share price and earnings. As they pondered the future, the stockholders adopted an alternative definition proposed by co-founder Gary Bewick: a company that would be independent and thriving in 100 years.

That premise lead inexorably to the employee stock ownership program, Foster says. “The real reason for our success is the people who have dedicated their careers to us, and the ESOP is providing a reward to them that we should have given earlier.”

ETC founder Fred Foster “is first and foremost a theater practitioner. That makes a huge difference in the products that we use.”

Mark Stanley, lighting designer, Boston University

The ESOP gives accumulated dividends to employees upon retirement — and a vote on proposals to sell the company. “If at some point the employees chose that, it’s their choice,” Foster says. “But this is a firewall.”

Foster clearly is having the time of his life, having attained a position with creative scope and fewer obligations than in the past, but he’s quick to share the credit. “If you get the best people, whose passions line up with the job, they can explore their passion in a direction that complements the company,” he says. “The best engineers want to develop the coolest products. The best customer service people want to delight the customer. If you find a way to let people explore their passions, you can’t lose.”

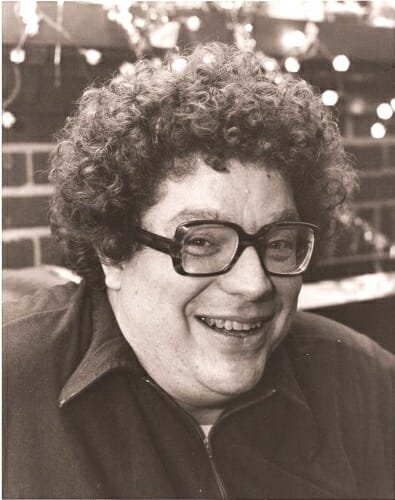

Lighting luminary: Gilbert Hemsley, former professor of theater

The founding of Electronic Theatre Controls in the 1970s traces directly to a charismatic professor of theater, Gilbert Hemsley. Hemsley, for whom a theater in Vilas Hall is named, “was a dynamic, exciting professor, who drew moths to the flame of his intensity,” as ETC CEO Fred Foster is fond of saying.

Hemsley, a lighting and stage management specialist, was professor at the UW from 1970 to 1979. Per his custom, he invited his undergraduate students to help set up his lighting designs at the Metropolitan Opera and Broadway shows in New York.

The undergrads became known as Gilbert’s “bunnies,” and while serving as a bunny, Fred Foster says, he “fell in love with the opera house, and we started with the goal of putting in a computer light board at the Met.”

On Christmas Eve 1975 at a party at Hemsley’s house, Foster and his three co-conspirators decided that they would build a digital lighting control. “We were sitting on his dresser and announced we were going to build a cue file (the computer file that links lighting changes to on-stage actions). ‘Sure you are,’ was the general reaction from the assembled grad students,” Foster recalls.

At Hemsley’s 1976 Christmas party, the ETC founders — two physics majors, a French major and a theater major — showed off their prototype digital lighting controller, called Mega Cue, which was used to control lights in the Wisconsin Union Theater around March 1977.

It was a success, despite some initial glitches.

Ellen Sorrin was a grad student at UW–Madison during Hemsley’s reign. Now director of the George Balanchine Trust, she also remembers Hemsley’s anything-is-possible inspiration. “He was absolutely the most generous person I have ever known in my life. I was in the counseling and psychology department and took Gilbert’s stage management class. I wrote my master’s thesis as a workshop for stage managers in assertiveness training and communication techniques. Gilbert invited me to teach it to his stage management class. It was a fantastic way of taking something theoretical and putting it into practice.”

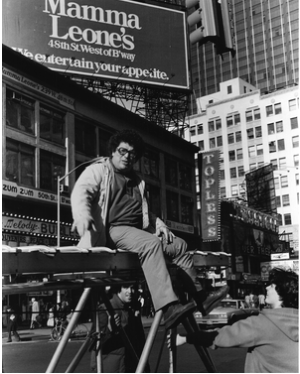

Gilbert Hemsley riding a lighting truss down Broadway, probably in the 1970s, while working on a performance in New York.

Like Foster, Sorrin was shaped by those work trips to New York’s theaters. “Gilbert was a magnet for people and he brought many students on jobs; there would be as many as eight students sleeping in his hotel room.”

Sorrin is president of the board of directors of the Hemsley Lighting Programs, dedicated to advancing young lighting artists. “We thought it might last five years,” she says, “but the fact that our program is still in existence since 1983 is a tribute from the people who passed through Gilbert’s life and were touched by him.

“Gilbert’s greatest gift was that he saw every production as a community of people. With Gilbert, it was expected that you would go the extra mile, no matter what, because that was what he did.”

Shortly before Hemsley died at age 47 in 1983, Foster proudly showed him ETC’s first brochure. “He was ill, but he asked about our product name, about our concept and even about our color choice.”

Now that ETC has placed its growing line of stage equipment in the Metropolitan Opera and other premier global performance locations, what would Hemsley say about the “bunnies” who began fetching sandwiches and aiming lights for New York designers four decades ago? Foster responded instantly: “Look what my students have done!”