Siftr: Web tool for citizen science, ethnography, teaching

In the world of Web apps, simple, intuitive and visual are the operative words. And an emerging app from the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery’s Field Day Lab called Siftr seems to be hitting all the right notes.

“The vision is to create a clearinghouse for the creation of citizen science projects,” explains David Gagnon, who serves as the program director for the Field Day Lab, a collaboration of researchers, educators, software developers, artists and storytellers engaged in creating new mobile media, game design and simulation. “It’s a tool to help teachers use the real world to inspire and illustrate learning, a tool to intentionally blend formal and informal learning.”

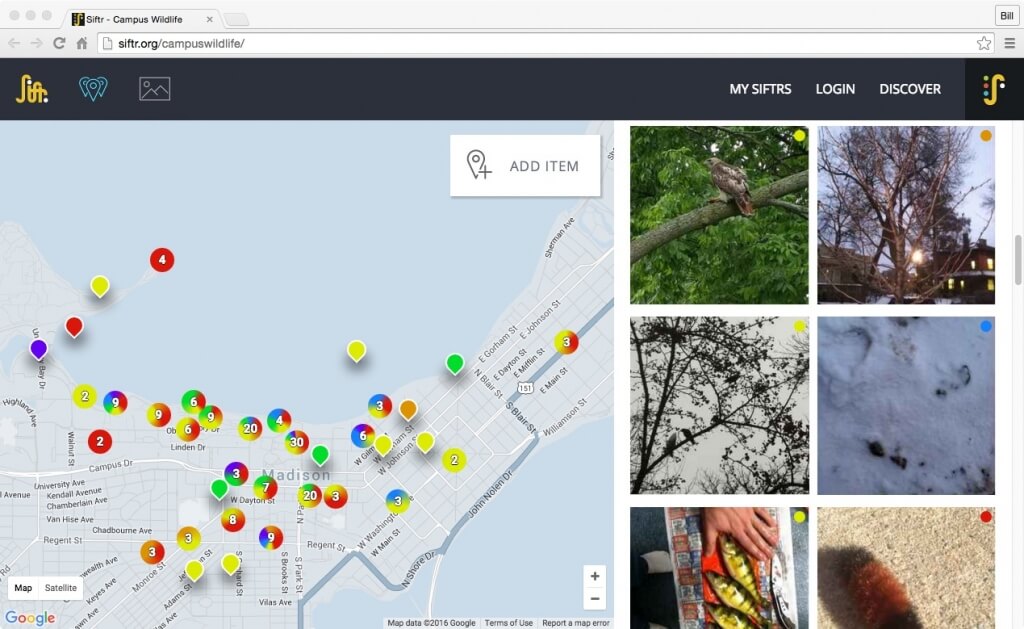

Siftr users set up pages around topics — in this case, urban wildlife — and participants upload images according to a direction set by the organizer. The page then generates a map, placing whatever object or phenomenon in its spatial context.

Introduced a couple years ago as a free and open resource, Siftr is already in use by hundreds of people in different corners of the globe and is gaining traction, especially among educators who use the app to help students explore the word around them.

“We wanted to build a technology that everybody could use for free, that could serve as an exchange and be a way to engage students,” says Gagnon.

David Gagnon serves as program director for the Field Day Lab, a collaboration of researchers, educators, software developers, artists and storytellers engaged in creating new mobile media, game design and simulation. Photo: Jeff Miller

Siftr users set up pages around topics, and participants — be they students, hikers, food cart aficionados, nature center visitors, cloud watchers, mitten finders, coffee sippers or graffiti trackers — upload images according to a direction set by the person organizing a Siftr. The page then generates a map, placing whatever object or phenomenon in its spatial context.

UW-Madison folklorist Ruth Olson began using Siftr two years ago beginning in the introductory Folklore 100. “I use it to have students practice sorting cultural items into different genres,” says Olson, who dispatched her students to get pictures of everyday art and stories as well as phenomena that conveyed traditions and folk groups.

Given that the assignment was over a football weekend, she ended up swamped with stories and images about UW football traditions. But students also came up with other creative Siftr entries like tattoo art, graffiti and what Olson call “latrinalia,” scribbling or art found on bathroom walls. Her students were required to follow up with an essay, so Siftr became the starting point for data collection and for interviewing various subjects.

“It totally made the point that culture is everywhere,” says Olson. “It also helped teach skills like photography and critical thinking: ‘What should I document and why?’”

For Gagnon, Siftr users like Olson are helping to validate the platform as a nimble, malleable educational resource. “It’s opening a whole new world of educational projects,” he says. “Our most common users are educators. It is a way for people to engage their environment and they don’t have to build all this technology.”

Another early Siftr adopter is the Nelson Institute’s Cathy Middlecamp. She uses the technology within the framework of Environmental Studies 126, Principles of Environmental Science.

“One of the learning goals of my course is to get our students to see the campus and the world with new eyes,” explains Middlecamp, whose 100-plus students have a three-hour lab period each week to explore things like energy efficient buildings, food choices, recycling and power generation.

After a recent snow, she unleashed her students on a quest to find evidence of the wildlife — birds, squirrels, even foxes — that share the 900-acre UW–Madison campus, adding to the eclectic mix of Siftr topics to be explored.

“Siftr is helping them see that humans aren’t the only animals on campus,” she notes, saying an added goal is to get today’s generation of students to work together and look up from the smartphone and computer screens that rule their lives. “If they look around, they see we’re not alone here.”

Siftr, according to Gagnon, is in constant development and his group is actively seeking others to engage with the Siftr platform and perhaps develop ancillary functions that can make the free resource even better. He is constantly discovering new Siftr endeavors like Anthropocene: Modern Fossils, a Siftr set up for this spring’s edition of the course World Environmental History.

“At the end of the day, Siftr is giving us new eyes to see the world.”

Tags: communications, computers, outreach, science