Retirement doesn’t end Warren Porter’s 50-plus years of research in zoology – it accelerates it

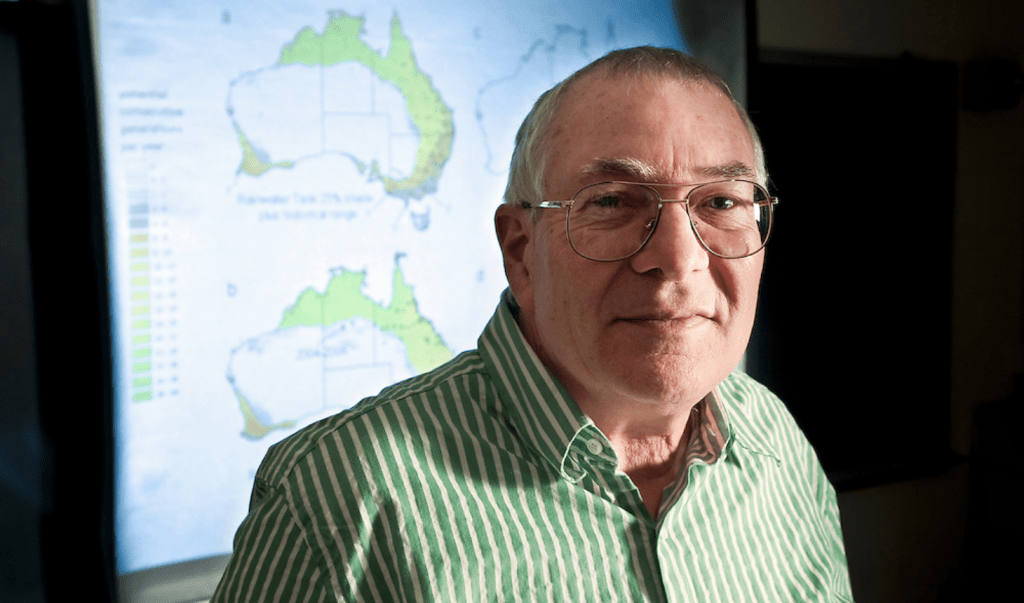

Professor Warren Porter has conducted wide range of research, including a look at the mosquito’s range over the next 40 years, pictured on the projected map of Australia behind him. Photo: Bryce Richter

On the first day of an undergraduate Zoology class, Emeritus Professor Bob Auerbach asked his students to write on a note card what they planned to do in the future. Warren Porter, though just a freshman, had known his answer for a long time: he dreamed of being a professor of Zoology.

Now, more than 60 years later and easing into retirement, Porter has clearly realized his dream. In his 50 years as a professor in UW’s Integrative Biology (formerly Zoology) department, he has helped lay the foundations of a pioneering new field in ecology, obtained nearly $10 million in funding for research, and contributed to more than 200 publications.

And yet, as the years transformed the campus’ squat buildings into skyscrapers and his own undergraduate students into leading professors in their own right, he is still an undergraduate at heart and in practice. For 50 years he has simultaneously lived the life of a professor and an undergrad, sitting in on every class, doing the homework, and taking the exams for 52 different classes across 19 different departments. He has exhausted the entire mechanical engineering catalog, taken courses on chemical engineering, atmospheric and oceanic sciences, computer science, and even learned in a digital 3D art class how to design and animate animals with the same tools that Disney uses in their animation.

He has gotten used to being the most incompetent one in the classroom. He says it is this process of being ignorant, learning, and growing that has formed the lifeblood of his research.

“Really, If you want to become technically competent you have to be willing to be an ignoramus again,” Porter said. “You can’t be satisfied with doing one thing.”

Indeed, many of Porter’s most important discoveries have sprouted from the spaces between disciplines and would not have been uncovered had it not been for the university’s singular interdisciplinary culture.

Porter works with a student in the Computer-Aided Engineering Center. The research involves using computer-modeled data to study the hydrodynamics of leatherback sea turtles. Photo: Jeff Miller

It was color-changing lizards that first sparked Porter’s zeal for interdisciplinary research.

While he was working on his PhD at UCLA, he made a crucial connection with Professor Ken Norris, who was interested in a type of lizard that, after leaving its burrow in the morning and warming up, became lighter and more reflective. Norris wanted to figure out how different colors allowed them to stay outside of their burrows for longer periods of time but needed to understand heat and mass transfer engineering first. Porter assisted, but once they started learning heat and mass transfer engineering, Porter found that they needed to understand computer science. And then physics. And then modeling.

By the end, Porter had spun a web of interdisciplinary connections so wide that it formed the basis of an entirely new field in ecology called “Biophysical Ecology,” which applies physical principles of heat, mass, and momentum transfer to animals to understand their ecology and behavior. Researchers in the field can now designate any animal anywhere on the planet and know what its food and water requirements will be, how long it will be able to be active each day and where it can survive, grow and reproduce successfully.

But the connections that Porter had helped make in one field of research would soon plug him into a wholly unexpected and different field of research. He feels that it is this newer phase of his career that will produce his best research yet.

When asked if he considers himself retired, then, he laughs.

“No, quite frankly. And I don’t want to. There’s still so much excitement and so much that I still want to do,” he said.

While Porter was working with Ron Hinsdill in Bacteriology (now called Microbial Sciences) in the 70s, Hinsdill mentioned in conversation that the chemical structure of a plant growth regulator being sprayed on wheat crops to make their stems thicker was almost identical in structure to an immunosuppressant used after transplant operations.

At the time Porter was just starting to dig into how pesticides might be influencing disease and Hinsdill’s comment gave him an idea: what if pesticides acted as immunosuppressants? Using EPA funds, he began to experiment with the chemicals and discovered that the greatest effects from the chemicals on immune functions came at the lowest – not the highest – doses.

At first Porter and his team though this was impossible. How could a smaller amount of chemical have a greater impact than a larger amount? They repeated the experiment four times expecting the first experiment to be a fluke, but each time the results came out the same.

As an undergraduate, Porter marched in the UW Marching Band all four years as a tuba player. At his retirement celebration, members of the marching band came to serenade him and celebrate his 50 years at UW.

They had discovered what endocrinologists already knew, which is that hormones at lower levels have a much greater effect than they did at high levels, even down to parts per trillion range. As before, Porter and his team formed connections with other disciplines and discovered that the immune, nervous, and hormonal systems were talking to each other all the time and that a tiny concentration of chemical – even just one drop in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools – could have vast and devastating impacts on a person’s health.

“I would never have seen it,” Porter said. “And I would never have had the conversation that led me to begin to realize how the animal population and the plant populations are being affected in subtle ways.”

The body and its countless intricate, complex, and interconnected processes means an interdisciplinary focus is practically required. We’re only just now beginning to understand how they all fit together and affect each other, Porter said.

For instance, he said roughly 70 percent of our immune functions come from the microbes in our gut. When a pesticide kills those bacteria, it can set off a chain reaction where the gut bacteria changes, causing a leaky gut and epigenetic changes in the gut lining and the body starts to mount immune responses, which in turn causes long-term, low-level inflammation, a precursor to ten chronic disease like diabetes, atherosclerosis, Parkinson’s and autism.

Porter said Madison was uniquely perfect for the type of work he has done for 50-years-and-counting. He said he has visited the major universities in every continent outside of Antarctica and said UW’s interdisciplinary culture is peerless.

“I’ve never been bored here. I’ve never gotten up in the morning and said, ‘Oh god I have another day of work,’” Porter said. “Instead I wake up feeling, ‘I can’t wait to get to my office.’”

“My retirement plans are not to stop what I am doing, but rather accelerate what I am doing in my research and to help the university and my department more in any way I can.”