Remembering Klaus Westphal, longtime former director of the UW Geology Museum

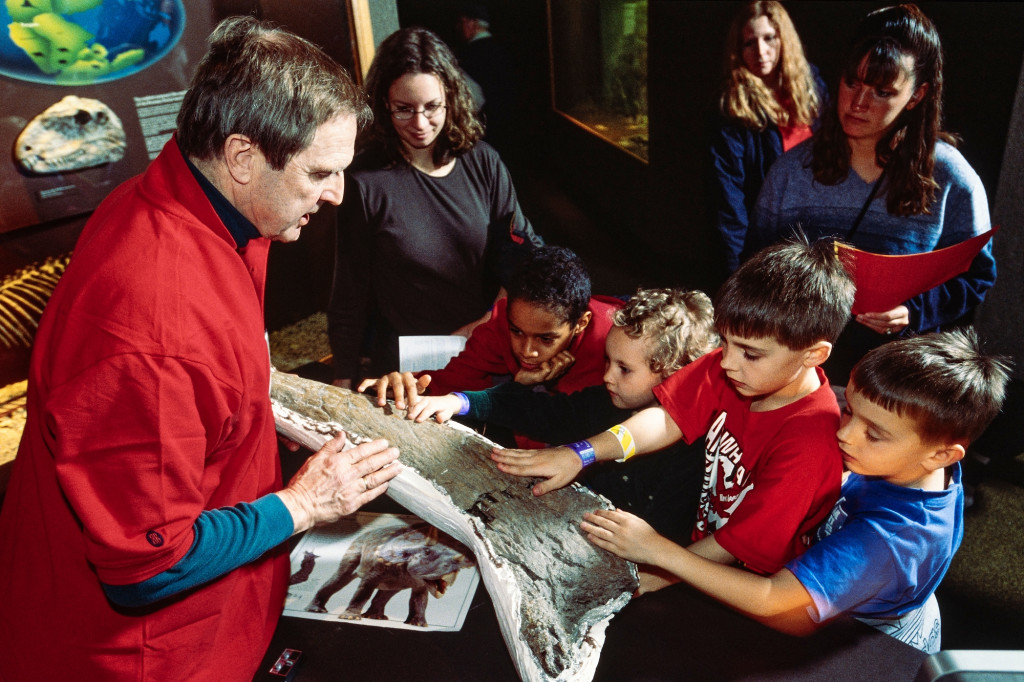

Children examine a dinosaur bone specimen while listening to Klaus Westphal, director of the Geology Museum at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, talk about digging for dinosaur fossils during a “Why’s and Wows” outreach program held at the Milwaukee Public Museum in 2002. (Photo by Jeff Miller / UW–Madison) Photo: Jeff Miller

Klaus Westphal, a lifelong learner who delighted in bringing science to the masses as the longtime director of the University of Wisconsin–Madison Geology Museum, has passed away. He died in Madison on July 31 at the age of 84.

Over his 34 years directing the Geology Museum, from 1969 to 2003, Westphal spearheaded its evolution from a relatively quiet — if impressive — collection of rocks, minerals and fossils into a bastion of scientific outreach on the UW–Madison campus.

Westphal oversaw the museum’s relocation from Science Hall to Weeks Hall in 1980 — a move that more than tripled exhibit space. He took great pride in making the museum more publicly accessible by expanding its hours and personally providing tours to countless visitors, including thousands of Wisconsin schoolchildren.

“Klaus was an exuberant host, especially when it came to welcoming people to the museum,” says Richard Slaughter, Westphal’s successor and the museum’s current director.

Pictured in 1995, Klaus Westphal kneels next to a collection of excavated and plaster-encased bones and fossils from a Tyrannosaurus Rex dinosaur that were collected on student field expeditions from the Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation in Montana. Photo: Jeff Miller

Westphal had a knack for drawing in friends and new acquaintances alike to learn about the wonders of the natural world on display in the museum, from dazzling mineral collections to a towering mastodon skeleton.

“Sometimes I would see Klaus giving a tour to what I assumed were longtime friends, only to discover that he had met those people earlier that day while riding the bus into work,” says Slaughter.

Charlie Byers, a professor emeritus of geology who taught and carried out research alongside Westphal for more than 30 years, remembers his former colleague as an “incredible leader.”

“I was always most impressed by his unstinting efforts to improve the museum,” says Byers. “Starting with a modest level of institutional support, Klaus augmented the collections and displays by persuasion on a grand scale, and his army of student tour guides, fieldworkers and preparators loved working with him.”

While today there are myriad venues and events aimed at welcoming the public to explore the science that occurs on campus, that hasn’t always been the case. For many years, the Geology Museum and its annual open house were among the most prominent opportunities on campus for the public to engage closely with science — and awe-inspiring exhibits. Those include the first dinosaur ever put on display in Wisconsin, thanks to Westphal.

Westphal with the Edmontosaurus annectens, a hadrosaur (or duck-billed dinosaur) from the Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation in South Dakota that was the first dinosaur skeleton to be on display in the state of Wisconsin and is still on exhibit today. Photo: Jeff Miller

“When Klaus moved the museum to Weeks Hall in 1980, he decided to fill some of that newly gained space with a dinosaur, and he spent several summers out west excavating bones with students,” says Slaughter. “That skeleton has now been enjoyed by more than a million people.”

Westphal is also remembered as an energetic and joyful teacher. He taught his signature course, Life of the Past, more than 50 times, according to Slaughter.

“It was essentially a semester-long tour of the museum,” Slaughter says. “His students were not only treated to his humorous lectures but also the sense of wonder he had for fossils.”

That sense of wonder lives on through the thousands of visitors who continue to flock to the museum every year to view its ever-evolving exhibits. Indeed, Westphal’s influence on the museum, and scientific outreach at UW–Madison in general, will continue to be felt for many years.

As Byers says, “The fact that the Geology Museum is a tremendous asset of outreach for the UW campus is the result of Klaus going way beyond his job description.”

Tags: geology, obituaries