Remembering ‘forgotten’ presidents on Presidents Day

Millard Fillmore

Two words: Millard Fillmore.

Who? He was president of the United States from 1850-1853, yet you won’t find him carved on Mount Rushmore. Turns out, not all American presidents have legacies — or even names — that are as familiar as George Washington.

In honor of Presidents Day on Monday, Feb. 17, University of Wisconsin–Madison political science Professor Ken Mayer shares some thoughts on how and why we remember some presidents more than others.

“One of the things I say to my students when they want to know who are the best and worst presidents, or most underrated or overrated, or most forgettable, is to point out that these questions are similar to asking who is the best or worst or most overrated or most underrated or most forgettable actress, or actor, or painter, or composer, or writer, or musician, or comedian, or movie,” says Mayer, who is also an affiliate faculty member in the La Follette School of Public Affairs. “Is ‘best’ the same as ‘favorite?’ How do you distinguish between, say, Katharine Hepburn, Vivien Leigh, Sidney Poitier and Laurence Olivier? George Carlin, Mel Brooks or Chris Rock?”

Many of these judgments, Mayer says, depend crucially on what the yardstick is and who is doing the measuring.

“It is impossible to ignore the role of political assessments of the policies,” Mayer says. “While both Lyndon Johnson and Ronald Reagan had a significant effect on policies during their administrations, it is much more difficult to get Republicans and Democrats to agree on the merits of those policies. Was Bill Clinton a good president because he balanced the budget, or a bad president because of the Monica Lewinsky scandal? Or should credit for balancing the budget go to congressional Republicans — and should they be blamed for overreaching on impeaching Clinton?”

James Buchanan

While who did a good job as president and who didn’t may be pretty subjective, what makes a president memorable, Mayer says, often falls under one of the following characteristics: they held office during crises or historical turning points (Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Harry Truman); had a significant effect on politics, or on the office and its development (Andrew Jackson, Theodore Roosevelt, Reagan); a high level of charisma or personality characteristics (John F. Kennedy, probably Barack Obama as well); or scandal (Richard Nixon, Ulysses S. Grant).

Other than Jefferson, Jackson and Lincoln, most 19th century presidents, such as Franklin Pierce, Fillmore, James Buchanan, Rutherford B. Hayes and Benjamin Harrison, have been largely forgotten — or have become punch lines, Mayer says.

“There were often important things that occurred during various presidencies, such as the establishment of the first Civil Service laws during the Chester A. Arthur administration,” Mayer says. “Pierce and Buchanan are faulted for exacerbating tensions over slavery. Hayes was known by critics as ‘Rutherfraud,’ because of the controversy over how disputed Electoral College votes were awarded to him, which gave him the 1876 election.”

The presidents most often regarded as “worst” — Buchanan, Andrew Johnson, Warren G. Harding, Grant — were either completely forgettable, involved in scandal, or made horrendous decisions, Mayer says.

That said, the tide can turn on a president’s reputation. When Truman left office in 1953 (opting to not run for reelection in large part because he knew he would lose), he was regarded as ineffective and corrupt.

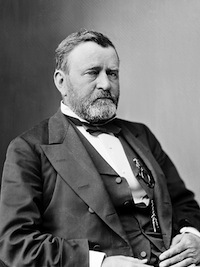

Ulysses S. Grant

“We now think of him as strong and highly rated (a 2009 survey of historians put him fifth, one slot below Theodore Roosevelt and one slot above Kennedy),” Mayer says. “Dwight D. Eisenhower was long regarded as a genial and absent-minded bumbler, detached from what was going on. More recent work shows that he was highly engaged (that same 2009 poll ranked him eighth).”

While presidents like Washington and Lincoln get all the attention, Mayer says there is plenty to learn about some of the less remembered presidents.

“William Howard Taft did a number of things that had a significant effect on the development of the office — he was the first president to try to put together a comprehensive executive budget in 1912, even though Congress tried to stop him,” Mayer says. “This played a role in the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 that established the first pass at a coherent budget process. He also was the only person to head two branches of the federal government, as President and then Chief Justice of the United States.”

And 68-year-old William Henry Harrison was at the time the oldest person ever elected president. He also holds the distinction of being the first president to die in office. After giving a nearly two-hour inaugural address in March 1841, he proceeded to come down with a respiratory illness, which turned into pneumonia (at least that’s the likely diagnosis, although there’s no way to be certain), which killed him 30 days later.

A president’s legacy, however memorable, is something that evolves over time.

“We remember recent presidents far more easily than past ones, and contemporary presidents are covered 24-7 the way presidents before, say, Kennedy or Johnson were not,” Mayer says. “But it’s hard to say what people will think 100 or 200 years from now.”