Q&A: Spinoza probably wouldn’t care, but debate over forgiving him goes on

Spinoza

This past Sunday, a crowd gathered in Amsterdam to watch a debate nearly four centuries in the making: Should the philosopher Spinoza be forgiven by the synagogue that excommunicated him in 1656? Among the participants was Steven Nadler, William H. Hay II Professor of Philosophy and Evjue-Bascom Professor in Humanities. He spoke about the experience with Inside UW–Madison.

Q. First, a little background for the non-philosophers among us — who was Spinoza and why was he excommunicated 359 years ago? How is he relevant today?

A. In July of 1656, Bento Spinoza was only 23 years old, and hadn’t published or even written anything — certainly not yet a famous philosopher. But that month he was put under “herem” (excommunication) by the Amsterdam Portuguese-Jewish congregation for his “abominable heresies and monstrous deeds.” It was the harshest excommunication ever issued by the community and it was never rescinded. However, the herem document does not tell us what exactly his offenses were.

He would go on to become one of history’s most important and influential — and vilified — thinkers. In his mature treatises, he argued that there is no such thing as a transcendent, providential God; God is Nature, and everything that is is a part of Nature. He also claimed that the Bible is just a work of human literature, and a rather imperfect one at that, whose only message is “love your neighbors and treat them with justice and charity”; and that Jewish law is an obsolete body of superstitious ceremonies that are no longer valid for latter-day Jews. He was, in addition, a proponent of democracy and freedom of thought and expression. These were probably just the kinds of things he was saying as a young man, around the time of his excommunication.

Spinoza continues to inspire philosophical, moral, religious and political thinkers with his radical ideas about religion; about the importance of a secular, liberal state with extensive toleration; and about the dangers of superstition and prejudice.

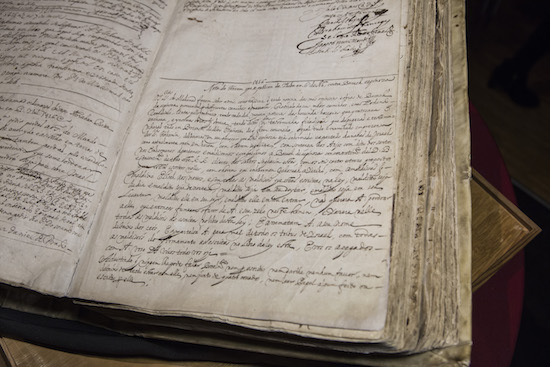

This is the original text of Spinoza’s ban, which was on display at the event. Photos courtesy of Steven Nadler

Q. How did the movement to reverse the excommunication come about?

A. In 2011, a member of the Amsterdam Portuguese-Jewish congregation asked for a reconsideration of the ban, with the hope that it would finally be lifted. (It seems to happen periodically that someone, somewhere, demands the ban to be revoked — the former Israeli Prime Minister David ben Gurion did so in 1953.)

The congregation’s leaders felt they needed more information, so they convened a committee of four scholars specializing in Spinoza and in Dutch Jewish history to advise them on the historical, philosophical and religious contexts of the case. We prepared our reports without consulting with each other, and were asked to consider the pros and cons of lifting the ban.

A year after we submitted our reports, we eventually learned that the rabbi had decided that, as powerful and important an intellectual figure as Spinoza was, there was no precedent in Jewish law for lifting the ban. He argued, too, that lifting it would be a dangerous precedent, given Spinoza’s attack on the foundations of Judaism. All this was done quietly, and with little public attention. But finally the congregation, with sponsorship by the University of Amsterdam and the CRESCAS Institute for Jewish Education (in Amsterdam), decided to hold a public event around the case and these recent deliberations.

Steven Nadler (left) speaks during a break to some of the more than 500 people who attended the discussion.

Q. You are one of four scholars invited to advise the synagogue’s rabbi on this matter — what sort of research have you done that’s relevant?

A. I am the author of a biography of Spinoza, as well as several other books on his philosophy and religious and political thought. I have also given many public talks on Spinoza and his ideas, especially in synagogues.

Q. Have you ever participated in something like this before? How did you prepare?

A. Certainly nothing on this scale, and it was very exciting and a great honor to do so. Philosophers rarely get the opportunity to take their scholarly work into the public domain and actually participate in something as consequential as this. I was also a bit intimidated, not knowing what the audience expected or how the participating rabbis would approach the whole issue.

Preparing was easy, since all I was expected to do was review what I took to be the reasons for the herem. In my view, it was a matter of his philosophical ideas (his “heresies”), although some other scholars have insisted it was for more practical violations of the Amsterdam Jewish community’s regulations, such as taking advantage of Dutch law to avoid debts (within the Jewish community) inherited from his late father.

“If we were to ask Spinoza himself what should be done, he would most likely say, ‘I couldn’t care less.’”

Steven Nadler

At the same time, I was nervous about presenting my own thoughts about whether the ban should be lifted. I do believe it is always and absolutely wrong to punish people for their ideas; on that point I’m in total agreement with Spinoza himself (not to mention the First Amendment). On the other hand, given the historical circumstances of the ban, it is totally understandable why the 17th century congregation reacted harshly to Spinoza’s ideas. I also think that lifting the ban now would be a meaningless act. And if we were to ask Spinoza himself what should be done, he would most likely say, “I couldn’t care less.”

Q. Describe the day and the debate itself — what was the experience like, both intellectually and emotionally?

A. This past Sunday, 500 people in Amsterdam showed up in the hall of a former “schuilkerk” (“hidden church,” where Catholics could practice safely in a fiercely Calvinist land) to hear a discussion of the case. Spinoza is a great hero of Dutch history, so the size of the crowd was no surprise. The four of us who made up the scholarly advisory committee made our presentations and outlined the essentials of the case. Then several rabbis and other scholars spoke, adding their own perspectives. One rabbi from Israel, in fact, exclaimed: “For God’s sake, lift the ban!” However, the current chief rabbi of the Amsterdam Portuguese congregation explained why lifting the ban would be wrong, and why he had no intention or even right to do so.

Q. What happens next?

A. One possibility is that, in light of Sunday’s event and the overwhelming affection for Spinoza shown by the huge crowd, the rabbi reconsiders his decision. This seems highly unlikely, however; these things are not decided by public popularity.

Of course, the Catholic Church reconciled itself with Galileo. However, that affair was quite different, since Galileo did not directly attack the foundations of the Catholic religion; his ideas were primarily scientific (although the Church did not see it that way).

Spinoza, on the other hand, launched a direct assault on the essentials of the Jewish faith. However, even if the herem is not lifted, it would be nice to see the congregation make a gesture and acknowledge the historical significance of arguably its most famous (if outcast) member, and especially his importance for Jewish intellectual history.