Old Watrous mosaic looks as good as new — meaning more like it did in 1963

Not many people can say they’ve spent endless hours with Abraham Lincoln.

Cricket Harbeck did. They even had birthday cake.

Harbeck is an art conservator. In 2009, she gave the Lincoln statue a good cleaning to coincide with the bicentennial of his birth (Feb. 12, 1809) and the 100-year anniversary of his arrival at UW–Madison.

Surface deposits from air pollutants, grit and bird droppings left their mark. Perched on scaffolding, Harbeck spent days cleaning and polishing the bronze sculpture, using a power washer, propane torch, wax and a series of hand brushes. The night before her last day of work, she checked up on Lincoln. Pink cake and frosting covered the 16th president of the United States.

An art conservator’s work is never done.

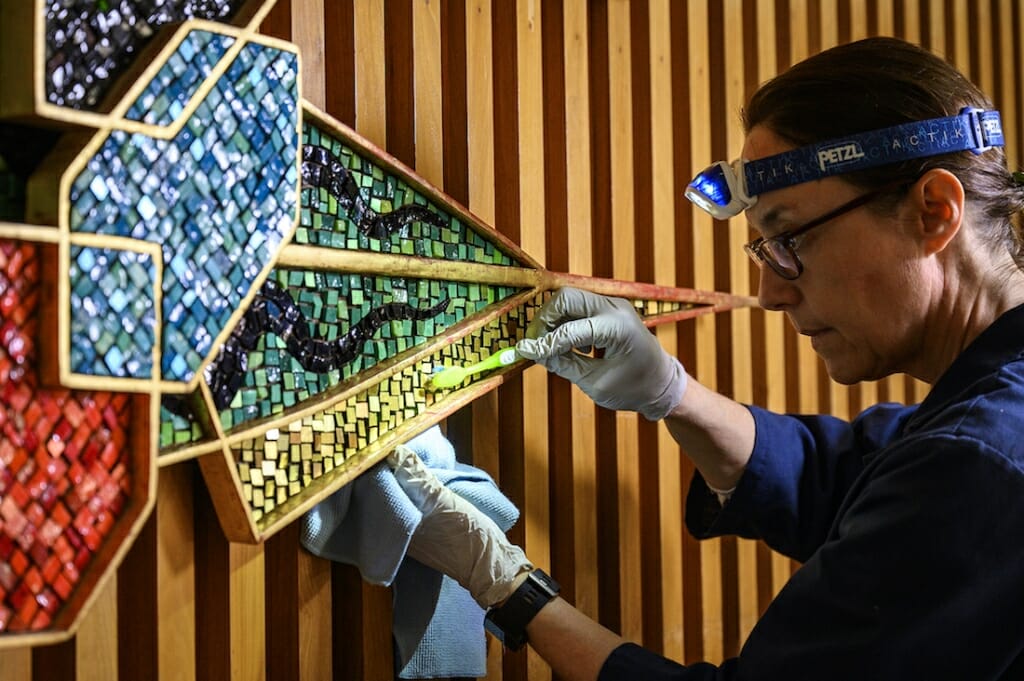

Harbeck returned to campus in May for another project, this time cleaning up “Man—Creator of Order and Disorder,” a mosaic by James Watrous in the William H. Sewell Social Sciences Building.

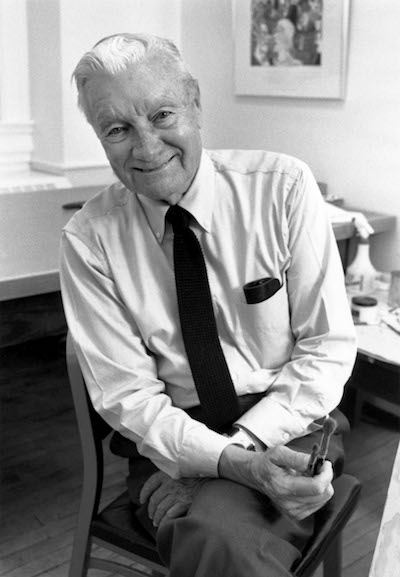

Watrous earned bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees from UW–Madison. From 1933 to 1936, he painted the Paul Bunyan murals in the Memorial Union. Watrous joined the faculty in 1935 and remained active in university arts issues and activities after his retirement in 1976. He was a campus arts advocate who helped raise funds to build what is now the Chazen Museum of Art. In 1999, he died at the age of 90.

His mosaics — artwork created by arranging pieces of material such as stone, tile or glass — can be found in Memorial Library, Ingraham Hall and Vilas Hall.

James Watrous joined the faculty in 1935 and remained active in university arts issues and activities after his retirement in 1976. He died in 1999. Photo: Jeff Miller

Installed in 1963, “Man—Creator of Order and Disorder” has endured more than 50 years of wear, subject to knocks and bumps in the busy building foyer that have caused fractures and surface damage. The piece has been a reluctant second-hand smoker back in the days when smoking in buildings was the norm.

“Sometimes I’ll hit a spot where it smells like I’m smoking,” Harbeck says. “That’s part of why it’s so difficult to clean. Nicotine is so tarry. It’s like a sticky trap for all the dirt.”

Her tools include a headlamp, hand brushes and several soft-bristle toothbrushes.

“I find pink ones work the best,” she jokes. “A lot of it is low tech and knowing how to use equipment and materials. It’s like any trade that way. You don’t always need fancy things.”

It’s long, quiet, detailed, solitary work. That’s why she’s enjoyed the curious passersby, especially the one who brought her a bar of chocolate.

“It’s like my own cheer squad every day,” Harbeck says.

Based in Milwaukee, her work has brought Harbeck to Turkey, where she has spent summers working at an archaeological site, and to Antarctica for seven months as part of a conservation team preserving artifacts from the expeditions in the early 1900s of explorers Captain Robert Falcon Scott and Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton.

As Harbeck worked, she saw notations indicating where things went. “That’s what I love about conservation. You get to see all these little details that the typical person wouldn’t see,” Harbeck says. “It makes it very intimate.” Photo: Bryce Richter

It’s been a fascinating career for Harbeck — and one that she didn’t always know existed. She earned her bachelor’s degree in art history and studio art from Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, and started working for a museum. That was when she learned about art conservation and knew that’s what she wanted to do. So she got her master’s in art with a certificate in art conservation from Buffalo State College in Buffalo, New York.

“When we look at artwork, one of our big concerns is how it deteriorates,” Harbeck says. “There’s a whole chemistry and physics of deterioration. “

That means knowing how different adhesives will react to the objects they’re preserving. It needs to be strong enough to do its job but not damage the object over the course of time; chemically stable but won’t yellow or become brittle years down the road.

Art conservators not only promise to do no harm, they make sure that what they’re doing can be reversible — if necessary.

“What makes conservation challenging is you’re trying to be as discreet as possible and not really show your hand,” she says.

There isn’t the glory of having everyone know it’s your work, but there is the occasional chocolate bar and satisfaction of helping preserve the creations of others.

“We’re caretakers really,” Harbeck says. “Our agenda is preservation.”

It’s long, quiet, detailed, solitary work. That’s why Harbeck has enjoyed the curious passersby, especially the one who brought her a bar of chocolate.

To help preserve her work, a rail-like barrier will soon be added to protect the mosaic as well as a new plaque and lighting to show the piece off.

As Harbeck worked, she saw little notations indicating where things went, most likely from when it was first installed.

“That’s what I love about conservation. You get to see all these little details that the typical person wouldn’t see,” Harbeck says. “It makes it very intimate.”

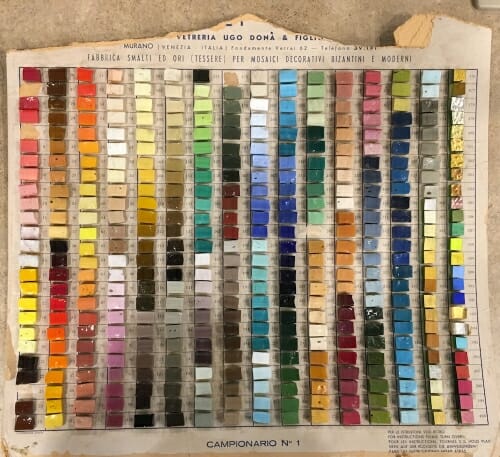

The original tessera supplier’s color chart James Watrous used was found in storage along with more than 250 paper Babcock ice cream tubs that kept surplus tiles in a rainbow of colors. Photo: Daniel Einstein

A few of the glass tessera tiles had to be replaced. Fortunately, campus historian Daniel Einstein found some in storage. More than 250 paper Babcock ice cream tubs kept surplus tiles that Watrous accumulated from his various campus projects between 1956 and 1977. The tiles were from Italy, where Watrous traveled in the 1950s to work as an apprentice in the studio of Giulio Giovinetti, a master mosaicist. Einstein even found the original tesserae suppliers color chart from which Watrous made his selections.

“One of the fun things about it is how lively the colors are. If you look at the yellows and reds, they’re all different types. He wasn’t using just one color,” Harbeck says. “It’s very thoughtful and very complicated. An incredible amount of thought went into it.”

Campus has more than 100 three-dimensional statues, mosaics, monuments, sculptures and memorial objects, often located in outdoor or high-profile public settings, according to Einstein.

“We’re caretakers really,” Harbeck says. “Our agenda is preservation.”

“These artworks help tell the story of the university and the state, from the Camp Randall Memorial Arch, to the statue of Governor Hoard on Henry Mall (who led us to become the Dairy State), to the stunning glass sculpture by Dale Chihuly at the Kohl Center,” Einstein says. “It is our responsibility to preserve the historic and artistic integrity of these artworks so that we may continue to be inspired by their beauty and recall the significant events of our shared history.”

After two weeks, Harbeck’s time with “Man — Creator of Order and Disorder,” came to an end. It’s always a little bittersweet to bid adieu after spending so much time with a work of art. She’s revisited her old buddy Lincoln and sees he could use a little care. If called, she’s ready with a pink soft-bristle toothbrush.

“They become like friends,” Harbeck says. “You get to know them intimately, all their little cracks and characteristics.”