Museum featuring works of UW’s John Steuart Curry

Many on campus get to see the works of John Steuart Curry often. But people off campus have an opportunity to see his artwork through Sept. 14 at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend.

Born in Kansas, Curry came to Madison in 1936 as the first artist in residence at any university in the United States. In 2011, many of his campus murals were restored, including “The Social Benefits of Biochemical Research,” a 1940s-era mural located in the stairwell foyer of the 1937 Biochemistry Building.

“The Freeing of the Slaves, ” a painting depicting emancipation, can be seen at the UW Law Library on Bascom Hill.

A collection of 21 of his works, titled “John Steuart Curry: At Home in Wisconsin,” is the first-ever exhibition to focus on Curry’s decade in Wisconsin and reveal his love of the state and its people.

Our Good Earth, oil on hardboard, 1942

Curry was one member of an influential triad of American regionalists that included Grant Wood from Iowa and Thomas Hart Benton from Missouri.

“Curry is the one who gets kind of neglected,” says Graeme Reid, director of collections for the Museum of Wisconsin Art, “but I have a particular fondness for him.”

The exhibit doesn’t just feature the finished project but also includes the sketches that inspired the paintings.

“I think a lot of people enjoy seeing the creative process,” Reid says, “and the drawings help with that.”

Curry worked as an illustrator for Boys’ Life and the Saturday Evening Post. His famous Kansas State Capitol mural “The Tragic Prelude” shows John Brown with his arms outstretched holding a rifle and a Bible.

Eventually, Curry made his way to UW–Madison as an artist in residence and the murals in the Biochemistry Building were painted from 1941–43. Curry died in 1946 but left a rich legacy.

View of Madison with Rainbow, oil on canvas, 1937

He painted the people and places he knew – often farmers working the land as depicted in “The Good Earth,” a painting of a farmer standing in a field of wheat with two children next to him.

“Curry clearly engaged with farmers,” Reid says. “This isn’t something he conjured up in his head. This is something he saw as he traveled around Wisconsin encouraging rural residents to pursue their artistic vocations.”

Some critics give Curry less respect because of that realism, Reid says, but his works resonated in Curry’s time and today.

“I think this show touches people because they can very much relate to it. It is art that a regular person can understand and relate to,” Reid says. “Curry loved what they loved. He truly felt that art should reflect the lives of ordinary people.”

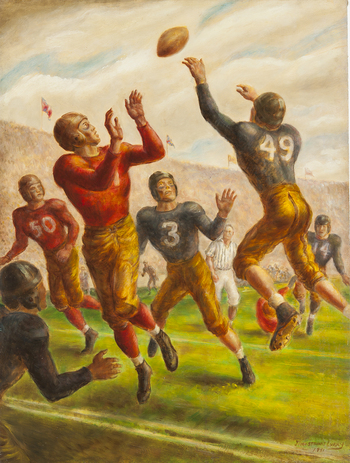

An All American, oil on canvas, 1941

Curry helped set up the Wisconsin Rural Arts Association, now called the Wisconsin Regional Artist Association, a nonprofit organization of more than 500 nonprofessional artists from the state of Wisconsin and beyond. WRAA works closely with the Wisconsin Regional Art Program (WRAP) through the UW–Madison Department of Liberal Studies and the Arts to provide educational resources, opportunities to exhibit, and encouragement to the artistic development of its members.

Reid sees Curry as a great example of the Wisconsin Idea, even though Curry wasn’t born here.

“Curry knew what it was like to be on the outside of the art world and not be taken seriously,” Reid says. “He had that compassion and empathy for others who felt they weren’t good enough or wouldn’t be taken seriously.

“That’s why he was so successful in Madison. He took amateur artists seriously, understanding that they were sincere and doing the best they knew how. Curry wanted to help them be better and achieve greater satisfaction through their art.”