Motivation, mentorship help deaf student reach for biology Ph.D.

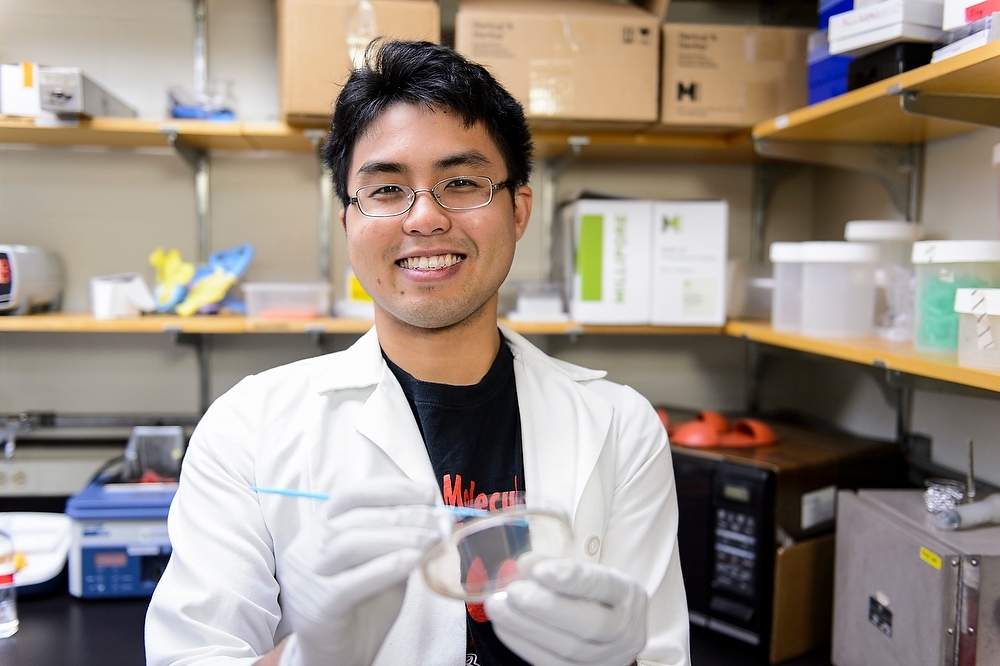

Phu Duong, a doctoral student in the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Cellular and Molecular Pathology Graduate Program who is deaf, works with cultures in Corinna Burger’s neurology research lab in Bardeen Medical Laboratories.

Taking a seat not far from a bench in neurology Professor Corinna Burger’s lab, grad student Phu Duong launches into a description of the research that drew him to the University of Wisconsin–Madison this summer.

“The proteins in cells are like Lego toys,” says Duong, a doctoral candidate in cellular and molecular pathology. “You want to understand their structure, how the smaller pieces fit together, and how changing the way they fit together changes the way the cell works.”

To get that point across, Duong delivers it simultaneously in two languages — spoken English and his first language, American Sign Language.

“I know it’s not often you see deaf people in grad school,” he says, referring in particular to the physical and biological sciences. “I think I only know one other, in physics. But in general, deaf people have less opportunity to go to college than their peers with no hearing loss.”

Deaf and hard of hearing students have earned doctoral degrees from UW–Madison’s schools of law, medicine and veterinary medicine, as well as many undergraduate and master’s degrees, according to Cathy Trueba, director of UW–Madison’s McBurney Disability Resource Center. But Duong is the only deaf or hard of hearing Ph.D. candidate on campus.

“In general, deaf people have less opportunity to go to college than their peers with no hearing loss.”

Phu Duong

Duong, who believes he lost his hearing due to meningitis around age 1, thinks the major hurdles to advanced study in the sciences are cultural.

“It’s difficult for deaf people to stay involved in the hearing world,” he says. “I remember how my peers in elementary school tended to be together, but isolated because they were focused inward.”

By design or circumstance, Duong says, he interacted largely with hearing people as he grew up.

“That was a challenge, too,” he says, speaking in part through an interpreter from the McBurney center, “because I had to learn how to conform to their culture.”

When he was just a toddler, Duong’s parents faced a similar cultural shift.

The family moved to the United States from Vietnam in 1990. The lives his parents had hoped to lead were upended by the Vietnam War. His mother had to leave law school as Vietnam shifted to communism, and his father was an officer in the dissolved South Vietnamese Army — which received particularly poor treatment from the country’s new leaders.

The family focused on survival, until they arrived in Chicago and began to assimilate. By the time Phu Duong was in school, he felt like a member of the American middle class — including opportunities that would set him on a path few of his deaf peers choose.

In high school, he found an internship with Northwestern University radiology Professor Gayle Woloschak, and developed a lasting friendship with Woloschak’s lab technician, Benjamin Haley. Duong and Haley would talk at length over a laptop, typing their conversation like an in-person chat room. Those conversations have continued via email over a decade, a friendship and connection to research that Duong carried from school to school.

Duong earned a bachelor’s degree in biology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and a master’s in structural biology at Northeastern Illinois University, but his studies built on an interest in science he had to foster on his own.

“I got lucky. I grew up with a computer and the Internet,” he says. “I feel confident about my ability to communicate in spoken English, but the experience with computers helped me to be able to talk to people. And it made science almost a self-guided activity for me.”

The importance of controlling the flow of information was immediately apparent to Burger, whose lab was one of three Duong rotated through in his first semester at UW–Madison, and who drew praise from an interpreter for her deft anticipation of communication issues.

“There are no signs for terms like ‘hippocampus,’ for ‘long-term potentiation.’ They need to be spelled out, and that’s where you can imagine the speed of conversation being a problem.”

Professor Corinna Burger

“I was surprised right away when I realized how fast we were speaking to each other in the lab,” says Burger. “My first language is Spanish, and I remember when I was a student how I had to work ahead to be prepared in the classroom just to follow scientific terminology in English.”

Burger is fond of American Sign Language — “so beautiful and onomatopoetic,” she says — but also grasped its shortcomings in the lab.

“It’s very simple,” she says. “There are no signs for terms like ‘hippocampus,’ for ‘long-term potentiation.’ They need to be spelled out, and that’s where you can imagine the speed of conversation being a problem.”

Duong, interpreter Paula Maciolek and other lab members bridged the gaps by developing shorthand and acronyms, and Burger tried to make sure Duong had electronic copies of lectures and presentations available in advance.

“I hope, because of technology today, that we have more deaf people like Phu coming into the sciences,” Burger says. “And I hope he picks our lab for his work. He’s a very hard worker.”

Tapping into that tenacity was an important step forward for Duong, whose graduate work is supported by UW–Madison’s Science and Medicine Graduate Research Scholars and a Molecular Biosciences Training Grant from the National Institutes of Health. He says he struggled in college until he found the assertiveness to make use of the services available to him and to confidently speak to people.

“It depended on getting over my shy side and having the right mentor — and I got lucky with a good one at Northwestern,” Duong says. “Maybe I could do that for other students with disabilities someday.”