More than a footnote: Remembering the life of William S. Noland, the first known Black graduate of UW-Madison

Today, the average college student leaves a daily social media mark, detailing what they’ve eaten, what they’re listening to, what they’re studying – or what they’re supposed to be studying.

It’s easy to take information, be it useful or mundane, for granted. That is until you try to put together the pieces of someone’s life who lived long ago.

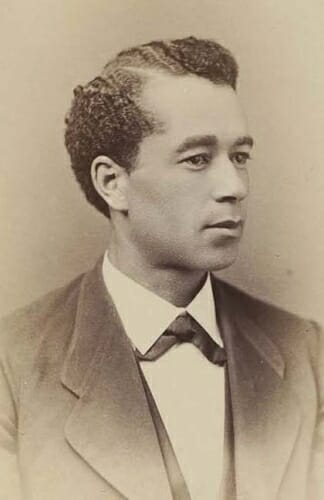

William S. Noland is believed to be the first Black student to graduate from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, receiving his degree June 17, 1875. This fact is often told but his story isn’t.

While there are none of the digital footprints students leave today, we can get a glimpse into his life digging into the archives, learning when he was born, where he lived, and when he was a student. But we also have his own words captured in the class album of 1875 and praise from his fellow students:

“He is adept at intellectual gymnastics and especially delights to use his powers against profs. He is the poet of the class and we believe in general aspires to literature.”

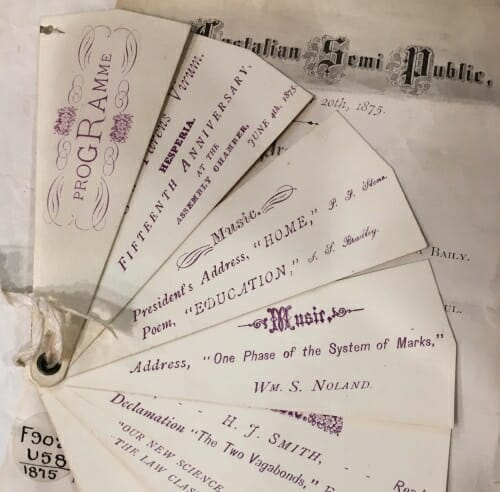

Noland earned a short critique from The Wisconsin State Journal as part of its extensive commencement coverage:

“The poem of Wm. S. Noland upon the subject ‘Yesterday – Tomorrow’ was a gem in itself, but too lengthy. Mr. N. will doubtless rank high as a poet at some future day.”

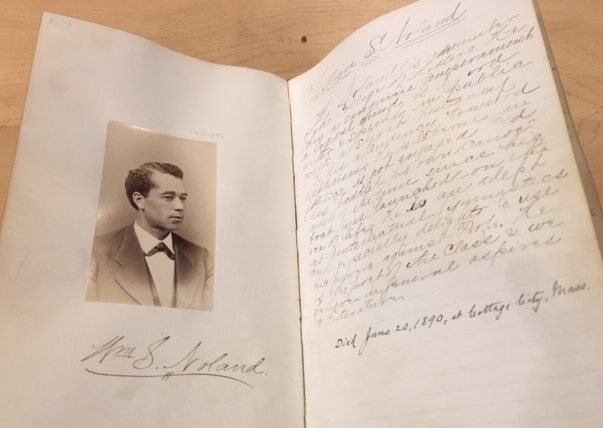

That was not to be. Sadly, Noland died by suicide June 20, 1890.

The passage of time takes the footprints of people’s lives with it. Traces get left behind, often bringing up more questions than answers. Noland’s story – or as much as we know of it – is a reminder that history is rarely simple.

William S. Noland was born Feb. 11, 1848 to Anna and William H. Noland in Binghamton, New York. The family, including his sisters Laura and Anastasia, moved to Madison in 1850. Frank and Charles were born in Madison. The Nolands are often credited as the first Black family to establish permanent residence in Madison.

On June 25, 1976, The Capital Times wrote a story about the family’s father, William H. Noland, and his role as a groundbreaker in Madison for its bicentennial section.

The story credits him with:

- Being the first Black person to establish permanent residence in Madison.

- The first Black person to be named to state office by a Wisconsin governor.

- The first Black man offered as a candidate for the office of mayor of Madison.

- Suggesting to Wisconsin Governor Alexander W. Randall that Black men be recruited for military duty at the outbreak of the Civil War.

His career was eclectic to say the least. Musician, baker, grocery operator, ice cream maker. Notary public, veterinarian, chiropodist.

He started out as a barber when he arrived in Madison in 1850 operating the Empire Shaving Saloon. In 1854, he refused service to a man identified as a slave catcher, telling him that he “did not shave kidnappers or their underlings.”

While the father, William H., was nicknamed “the professor,” it was actually William S. who was the family member who went to college. Records show him first registered as a student at UW–Madison from 1862-63 when he was 14, later returning as a student in 1869.

There were 31 students in the graduating class of 1875. Before there were Badger yearbooks, class albums were handwritten. Page after page of cursive writing provides a brief biography of each of the graduates along with a portion of the biography using the graduate’s own words.

Think of it as 19th century LinkedIn:

“Born Feb. 11, 1848, in Binghamton, Brown County, N.Y. A follower of the ‘star of empire’ in ’50 – a pupil in the common schools of Madison from the age of 7 to 14 – and a basically prepared student in the Classical department of the University of Wisconsin from ’69 to ’75 with a year & one half travel between the junior and senior years.”

While his father pursued numerous business ventures, his son had other interests.

“Mr. Noland is a member of the College of Letters. He has a sanguine temperament, a logical mind, and is a good writer & speaks in public with a slight hesitancy. He has a tendency toward skepticism. He is liberal in politics, is not engaged and has ‘paddled his own canoe’ most of the time since his boat was launched on the sea of life.”

In Noland’s own words:

“The filling up of this skeleton of my life would read very much like Mark Twain’s diary. ‘Got up. Eat breakfast. Eat dinner. Eat supper. Went to bed,’” Noland says of himself in the album.

In addition to their age, class members were asked to include other information about whether they used tobacco, consumed alcoholic drinks, their religion, and curiously, their height and weight:

“Never having used tobacco in any form or alcoholic drinks, the age of 27 yrs, 4 mo and 5 da find me 155 ½ lbs in weight; 5 ft 10 in. in stature, a member of the Hesperian Society; a disbeliever in secret societies in general; perfectly willing that anyone who chooses to believe himself a lineal descendent of the Old Man of the Sea should do so; a believer in free trade when I am making the trade myself and in hard money when I can get enough of it; a believer in an educational basis of suffrage; an admirer of Shakespeare, Byron & Moore, Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Miss Muloch, Bancroft & Macaulay, and Prof. S.H. Carpenter as the best teacher in the University or out of it.”

It continues:

“Wholly self-supporting since 13 yrs of age with annual expenses theoretically somewhere in the neighborhood of $325 but practically that amount of money failing to cover them; lastly, dependent for my recommendation to Society upon loveliness of character, rather than upon beauty of person. My favorite studies are Latin and ‘poor humanity.’ In religion, I say what I’ve a mind to and think what I please. My core being ‘He that thinks he knows most about heaven is going to be the most fooled. ‘

“Before entering college and during my continuance therein, I got my living in all sorts of ways, and nobody knows what I shall do when I get out.

“’So mote it be,” he concludes.

Noland was 27 when he graduated from UW–Madison. The last years of Noland’s life are much harder to put together. He was a student at the Law School for a short time “but was compelled to abandon his studies there and begin the work for daily bread,” according to the Wisconsin State Journal. “He went east and engaged in literary work, but was lost sight of by old acquaintances here until the letter, received Saturday afternoon, announced his death.”

“He was boarding with Mrs. Lucy J. Smith, No. 16 Kennebec Ave.,” the Vineyard Gazette reported. “He had been a summer visitor to the island for four or five seasons, and came here from Providence for a short time also. Mr. Nolen (sic) was a sufferer from dyspepsia, which at times took the form of colic.”

Judge J. H. Carpenter received a letter from L.R. Southworth of Providence, Rhode Island telling him that Noland died, according to the Wisconsin State Journal.

“Mr. Carpenter says Mr. Noland was a gentlemanly, quiet, well read man, a great student of Herbert Spencer, and was apparently engaged in literary work.”

Putting history’s puzzle pieces together

Noland’s story remained in the archives until May 1987, when the Wisconsin Alumnus attempted to answer the oft-asked question: Who was the first Black student to graduate from UW–Madison?

University records didn’t ask about race back then, the article states. Without written documents, a university archivist paged through old yearbooks. He came upon Noland’s picture.

“Maybe, probably, we now know the name of the first Black graduate of the University,” Tom Murphy writes in the Wisconsin Alumnus article, acknowledging the less than conclusive answer.

When Harvey Long, a native of North Carolina, was a doctoral student in library and information studies at UW–Madison, he started a project on early Black students. Long, now a librarian and assistant professor at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, pored over yearbooks, the UW–Madison archives, newspaper articles and the Black press for any information he could find and completed an archives-based examination of the period between 1875 and 1940.

“This was something I became interested in once I moved here, because the narrative — that Black students or African Americans did not come here until the 1960s — was just not right,” Long says.

He discovered that the history went back much further than many might think.

Among the students he “met”:

Leo Butts, the first known Black graduate of the University of Wisconsin School of Pharmacy, as well as the first known Black athlete to appear in a game for the UW varsity football team.

William T. Green, who graduated from the University of Wisconsin Law School in 1892. Green practiced law in Milwaukee and was a leader in the Black community.

George Coleman Poage, who graduated with a B.L. Poage was a member of the varsity track team, breaking several records in dashes and hurdles. He would become the first Black athlete to win an Olympic medal in 1904.

Mabel Watson Raimey, who earned a B.A. in 1918, becoming the first known Black woman to graduate from the university. She attended Marquette University Law School and was admitted to the Wisconsin Bar in 1927. Raimey was the first Black woman attorney in Wisconsin.

Jimmie Elmer Tyler, class of 1924, moved from Lexington, Kentucky to live with relatives in Madison. Tyler’s senior thesis was “A Study of the Amount and Character of the Teacher-Training Offered in Negro Normal Schools.” After graduation, Tyler joined the Dallas School District to train African American grade school teachers.

Freddie-Mae Hill, who taught home economics at Booker T. Washington’s famous Tuskegee Institute after receiving a B.S. in home economics in 1928. Her senior thesis was “The Evolution of Textile Printing.” Hill was born and raised in Atlanta. While visiting relatives in Wisconsin, her father decided to move the family to Madison. Her parents owned and operated Hill’s Grocery in Madison for more than 50 years. Today, the Hill building has been designated a Madison landmark.

Ida, Carlita and Frances Murphy, who came from Baltimore starting in 1935. The sisters all earned journalism degrees and after returning home, “kept their father’s newspaper, the Baltimore Afro-American, afloat,” Long says. The paper had “a storied history,” he adds, and survives as the website www.afro.com.

And of course, Noland. In 1875, Noland had a college degree, something rare for anyone, let alone a Black man. It wouldn’t be until 1918 that Mabel Watson Raimey became the first known Black woman to receive a degree from UW–Madison.

Noland’s family moved to Madison in search of opportunity. William S. Noland may have moved back east for the same reason. He lived in Philadelphia and was a reporter.

“He was living in an area where Black folks did not live,” Long says, basing this on Noland’s address listed in the census, which also lists him as white.

“People often passed as white to have access,” Long says. “He was very light-skinned and in a world that demarcated people by their identities, I think it’s important to articulate that. He could basically remake himself into who he wanted to be or who he felt he was. He wasn’t under the shadow of his father. Noland lived when some people thought African Americans were not even human.”

But access came at a price. Passing often meant severing all ties with family members, which it appears Noland did. Besides Philadelphia, he also lived in Washington, D.C. and in Providence, Rhode Island. We don’t know if he ever came back to Madison.

“Passing is so complicated,” Long says. “People think of it as an opportunity but there can also be a sense of loss.”

Harvey Long looks through photo albums from the 1870s and 1880s while doing research at University Archives and Records Management Service in Steenbock Library in 2016. Photo: Jeff Miller

There’s so much about Noland that we can’t know. But we know that living as a Black man in Madison or passing as a white man out east would have been difficult for so many reasons.

“History is full of gaps. It’s messy,” Long says. “You have to draw a lot of inferences. Some things you just can’t know.”

While history loves stories of triumph and overcoming obstacles, the reality is that many stories are hard not only to tell but to hear.

“Noland died at 42. That’s pretty young. He has all the tools and yet he doesn’t succeed,” Long says. “We have to think about these things and tell these complicated stories.”

When Long came to UW–Madison, he worked and studied in buildings mostly named after white men. It wasn’t until he started researching the stories of early Black students that he felt like he belonged.

“All types of students have attended the university. Those different experiences make us who we are,” Long said. “When people see themselves represented, that’s a great feeling.”

History is complicated, and for good reason. We can’t speak to the people who lived it so we gather whatever information we can to piece together parts of lives that lived so much more than we’ll ever know.

The editors of the 1875 class album knew this. They acknowledge that despite their best efforts, the history they’ve put together can only be so accurate.

“There are many errors in this book and we can only plead the usual cry of authors – ‘It was done in a hurry.’ We ask our friends to overlook them. It was for no honor or glory that the editors undertook this long and tedious task but as a duty laid upon them by the class that in the future it may be of some interest to other classes.”

It is indeed.

While it is certainly more succinct to summarize William S. Noland as the first Black person to graduate from UW–Madison, his story – like all of ours – is more complicated.

Questions will always remain. Perhaps asking is the best way to honor him.

You can read about Long’s research here and here.

Read about Mabel Watson Raimey, believed to be the first Black woman to graduate from UW–Madison, here.