Made-in-Madison skin replacement starts final clinical trial

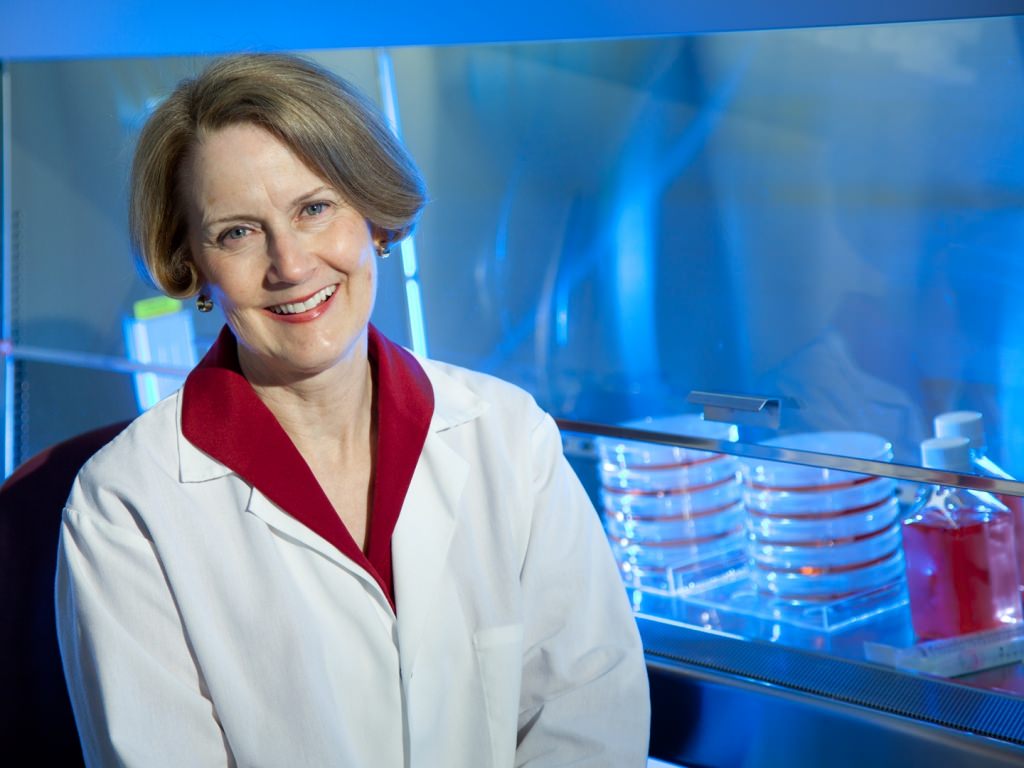

Lynn Allen-Hoffmann formed Stratatech and is working to transform a discovery into a biological treatment designed to speed healing of severe burns. Photo courtesy Stratatech, a Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals company

A University of Wisconsin–Madison spinoff that makes an innovative material designed to speed healing of serious burns has begun a large clinical trial for the “regenerative skin tissue” it has been developing since 2000.

Stratatech, now a Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals company, aims to prove to the Food and Drug Administration that the material, called StrataGraft, is safe and effective for treating severe burns. Intense burns can be painful, even deadly, because they destroy key protections against infection and dehydration.

Today, treatment involves removing a portion of the patient’s intact skin and grafting it to the burned site. In contrast, StrataGraft is designed to cover deep burns with a matrix containing human skin cells.

These cells, called keratinocyte progenitors, are able to form the epidermis, or top layers of skin. It is possible that the progenitor cells also produce and release growth factors that stimulate regeneration of the patient’s own skin cells, yet evoke a very limited immune response.

In 2015, after its second clinical trial, Stratatech announced that StrataGraft had fully closed deep, partial-thickness burns on 27 of 28 patients in three months. “Patient outcomes in this study far exceeded our expectations, and are unprecedented in this patient population,” Stratatech founder Lynn Allen-Hoffmann said in a 2015 press release. “This is the first severe burn therapy that has shown the potential to avoid painful skin transplants and regenerate the patient’s own skin.”

In August 2016, Stratatech was purchased by Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals of the United Kingdom. Its offices, and about 60 employees, remain in University Research Park in Madison.

Allen-Hoffmann is on leave from her position as professor of pathology and surgery at UW–Madison’s School of Medicine and Public Health.

StrataGraft has completed two rounds of clinical trials. The make-or-break phase three trial that has now started will be performed over several years at multiple sites nationally.

Stratatech aims to prove to the Food and Drug Administration that its material, called StrataGraft, is safe and effective for treating severe burns. Photo courtesy Stratatech, a Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals company

In an interview, Allen-Hoffmann says she’s studied skin cells for her entire career, “to understand their growth, differentiation characteristics, and how certain environmental chemicals affected them.”

The product is based on certain unique cells that appeared in Allen-Hoffmann’s lab in the late 1990s. After her technician, Sandy Schlosser, pointed them out, “I can distinctly remember saying, as I was sitting at the microscope, ‘I think this colony of keratinocytes looks amazingly basal,’” Allen-Hoffmann recalls. In other words, they looked like keratinocytes located in the first layer of human skin. These cells are in large part responsible for producing the remaining upper layers of skin tissue.

“We characterized them biochemically in many different ways, sequenced certain genes and could not find a difference between them and their parent cell,” Allen-Hoffmann says.

Although the cells had an extraordinary ability to survive in culture, they were not malignant.

“It was fascinating,” she says. “When cultured appropriately, they can recapitulate the 3-D architecture of skin tissue. They made a wonderful model system for research on skin biology.”

Along the way, Allen-Hoffmann contacted a UW–Madison burn surgeon, looking for advice on applying the material to animals for research purposes. But he changed the subject to talk about the need for a better treatment for catastrophic burns (see sidebar).

Little did Allen-Hoffmann suspect that this meeting would ultimately become an important example of the value of basic research and discoveries to the quality of life for those in Wisconsin and far beyond, in the spirit of “The Wisconsin Idea.”

In 2000, armed with several patents from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, Allen-Hoffmann formed Stratatech and began the painstaking process of transforming a discovery into a biological treatment. In time, Stratatech developed a process to “seed” a dermal equivalent with its special cells, performed pre-clinical animal tests, and then followed with manufacturing StrataGraft under the FDA-mandated “Good Manufacturing Practice” at Waisman Biomanufacturing on the UW campus.

In 2007 StrataGraft’s potential appeared with the first human patient. Within a week or so, Allen-Hoffmann says, “the surgeon called to say the material had become adherent to the wound bed, there was no acute immune response, and it was ‘pinking up,’ indicating a new blood supply. ‘Why don’t we leave it on, it’s looking good.’”

For the sake of caution, the trial required removal of the skin substitute after seven to 10 days, but the first results were no fluke. StrataGraft was left in place in subsequent studies, and even though it was getting a blood supply, the DNA of the implanted cells was not found in patients after three months.

As it stands now, StrataGraft is being investigated to see how it adheres to the wound to protect against infection and dehydration. Then, like normal skin, it falls off. “This is not inconsistent with how our skin functions in life,” Allen-Hoffmann says. “The cells differentiate, move up, and ultimately fall off the body.”

Tests to date have compared StrataGraft to the current standard of care, called autografting. This skin graft transfer of the patient’s healthy skin does cover the burn site, but it creates additional wounds that are painful and subject to infection, and the results are inconsistent.

“The whole goal in these proof-of-concept studies was to remove less uninjured skin, thereby avoiding yet another painful wound,” Allen-Hoffmann says. “So we have shown that we could treat individuals who would have required autografts. We are now in a phase three clinical trial for StrataGraft, with a larger patient population than earlier trials, testing it in deep, partial-thickness burns.”

At three months, the trial will measure the percentage of the StrataGraft treatment site that requires a subsequent autograft, and the proportion of subjects that have achieved durable wound closure of the StrataGraft treatment site without autograft placement.

A success could satisfy FDA requirements for approval to market StrataGraft to treat serious burns. Angela Gibson, a faculty member in the Department of Surgery at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health, has enrolled the first patient in the phase three trial.

Allen-Hoffmann and Stratatech have had plenty of support in their pursuit of a solution to burns and other hard-to-treat skin lesions. In October 2015, the company was awarded a contract from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to produce its regenerative skin product for stockpiling in preparation for a domestic mass casualty event involving burns, such as a terrorist or military attack.

On Jan.10, Allen-Hoffmann received the Tibbetts Award from the U.S. Small Business Administration. The award recognizes businesses that have received Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer awards.

But she is the first to stress that none of this progress would have been possible without the citadel of research and expertise at UW–Madison. “It’s an incredible convergence of a great academic center, with a serendipitous discovery, and NIH (National Institutes of Health) support for basic research that enabled someone like me to observe something and follow up on it, a Department of Defense program that enables the development of such technology, and NIH support for small business innovation and technology transfer.

“It started at UW–Madison, and this is exactly why this great research university and the system schools are so important to the welfare of Wisconsin’s citizens and the future of our state economy.”

From research question to personal mission

The genesis of Stratatech includes years studying basic skin biology by Lynn Allen-Hoffmann, a professor of pathology at UW–Madison, and particularly the unique human cells that appeared in her lab in the 1990s.

As Allen-Hoffmann explored the biochemistry and genetics of those cells, she visited a burn unit at UW Hospital, which is certified as a Level One burn center, and described her results to burn surgeon Michael Schurr. He sat silently, then commented, “You have no idea what I need.”

What he needed became obvious months later, when Allen-Hoffmann watched surgery on an Illinois farmer with burns across 95 percent of his body after a propane explosion.

The farmer’s treatment originated with cells taken from one foot, which had been protected by a leather boot. At a facility in Boston, the cells had been separated and grown one layer thick, ready for implanting about a month later.

Although the farmer lived about six years after the arduous surgery and recovery, Allen-Hoffmann concluded that Schurr was right. “He did not have many options.”

In mid-afternoon, she left the surgery while it was still underway to attend a basic research seminar. “I’m sure the speaker was very talented, but I remember staring at a slide and thinking, ‘What I just saw in the operating room is what I should be doing,’” she says. “That was the epiphany that has defined my efforts ever since.”

She has doubtless told this story many times, but the edge remains sharp. “It’s been such a profound experience, even though I have been doing this for a number of years, it seems like it started yesterday.”

Great ideas sprout in great locations, Allen-Hoffmann says. “This could not have been done in isolation, and I’m very grateful to the university for allowing me to pursue this. It’s not as if I was experienced in starting a company. I was very passionate about it, and needed to see how far I could get.”