Land-grant faculty prioritize public engagement, but feel isolated

A survey of more than 6,200 faculty at 46 land-grant universities and colleges in the U.S. revealed that most faculty prioritize engaging with the public about science but feel isolated in their outreach work.

That isolation is driven by a gap between faculty’s belief that engagement is important and the perception that their peers don’t feel the same. Less than a quarter of faculty thought their colleagues prioritized science communication. In turn, the report finds, that isolation could weaken the participation in and effectiveness of outreach programs that meet university missions and the goals of the scientific community at large.

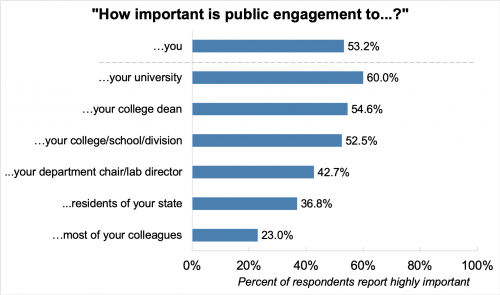

Land-grant university faculty were asked how important engaging with the public was to them, and how important they felt it was to their leaders and colleagues. While most faculty ranked engagement as very important to them, they felt that it was less important to their peers. Image provided by Dominique Brossard

“When you have a disconnect between what is important to you and what you think is important to other people, that means you feel isolated, even if you’re not,” says Dominique Brossard, a University of Wisconsin–Madison professor of life sciences communication and senior author of the report. “That means institutions need to be clear in saying that they welcome this kind of thing, that it’s something that’s important.”

Brossard published her findings Jan. 7 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in collaboration with Kathleen Rose at Dartmouth College and Ezra Markowitz at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The team sent surveys to over 100,000 faculty at all 73 U.S. land-grant universities and colleges to gauge their attitudes toward public engagement. The final dataset was narrowed to schools that had enough representative responses.

Nearly everyone who responded said they had participated in some science communication activity in the last year, such as a public forum or classroom visit. A little over half of faculty reported that public engagement is very important to them. Younger faculty were even more likely to prioritize this engagement.

Most faculty also thought that outreach is important to university leadership and the school at large. Yet they felt apart from their peers. Just 23 percent thought that public engagement was very important to their colleagues, despite the reality that a majority prioritize it.

Somewhat surprisingly, only about a third of faculty thought that engagement was very important to the residents of their state. The study didn’t survey the public to assess their views on this kind of engagement.

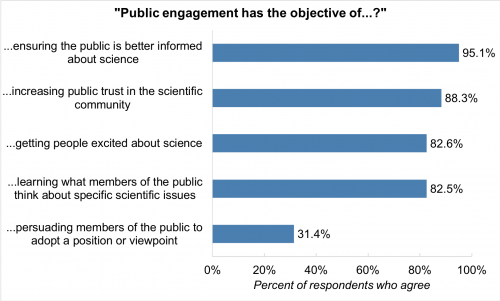

Faculty largely believed that the purpose of public engagement included building relationships with the public, rather than trying to persuade them to adopt a certain position. Image provided by Dominique Brossard

Brossard and her team also asked faculty to define the purpose of science communication. The vast majority viewed outreach as an opportunity for what Brossard calls “holistic” engagement, such as getting people excited about science and learning what the public thinks about scientific issues. Less than a third of faculty said that the point of engagement was to persuade the public to adopt a certain position, which research suggests is not effective.

The study was motivated by the calls that scientific societies have made for years for faculty to increase their engagement with the public. Their goals include boosting participation in science; increasing support for science-based programs, such as public vaccination campaigns; and helping society grapple with big changes brought by scientific advances. Past studies of how these campaigns align with faculty priorities have been small and incomplete.

“We don’t have the luxury of avoiding public engagement,” says Brossard. “Science is moving very fast. We are talking about things such as gene drives to control pests, human gene editing, and artificial intelligence that are moving way faster than our ability to regulate them. We need citizens to be part of those conversations.”

Brossard says that professional rewards tied to public engagement could both incentivize faculty to participate and signal that these activities are important to the university. For example, public engagement could be weighted more heavily when faculty apply for tenure, which is typically decided based primarily on research and teaching activities.

The researchers are now analyzing the data school-by-school to identify how mission statements, incentives and leadership values influence faculty attitudes toward public engagement.

“The main takeaway is that the perceived importance of public engagement for researchers is really increasing,” says Brossard. “However, they don’t feel they get the support they need. And although they think that members of the public have important things to say about science, the leadership at the institution may not be promoting these activities the way they should.”