Ken Raper recalls wartime penicillin research

RAPER: Because at Peoria the very early work in this country around penicillin was begun. It was begun because this man Thorn that I mentioned earlier had been consulted by the president of the National Academy of Sciences to whom the people from England, Florey and Heatley, had come for help. President Jewett sent them to Thorn and asked his opinion. Thorn said, “Send them to Peoria,” because there were people there who had worked with other mold fermentations. I guess it was in—the date I don’t remember—in 1941 they came to Peoria in July and we began to work with them.

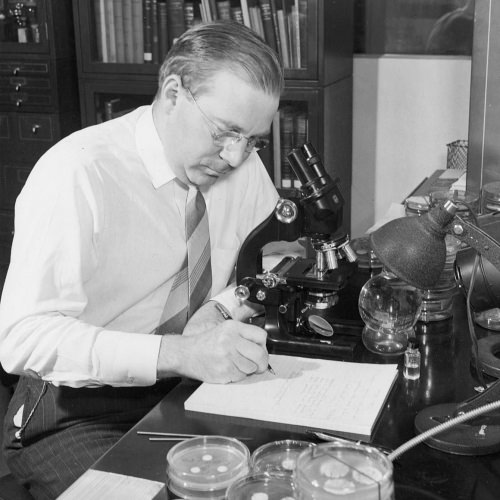

Kenneth Raper working in the laboratory in 1949. Professor Raper had dual appointments in bacteriology and botany. During World War II, he conducted research at a USDA lab in Peoria, Illinois, and identified a better strain of penicillin-producing mold. He later joined the faculty at UW–Madison. UW-Madison Archives

For the next four years the laboratory there was something of a center for penicillin work in this country. In that work my particular mission was to examine cultures for their ability to produce penicillin. We had a large collection that I had brought out from Washington, we screened those, we got in molds from all over the world almost for tests. We finally found the mold on a cantaloupe in Peoria that was quite good; it was better than anything else they had at the time and so we began to work intensively with that. We made selections from it that gave yields higher than the parent and in the meantime, the U.S. government working through agencies like the Office of Scientific Research and Development had set up penicillin projects around the country.

Upon the basis of the know-how here at Wisconsin—you mentioned McCoy and Marvin Johnson and others, people in botany as well—they set up a project here. And since the culture that we had isolated in Peoria was better than any that they had to work with at that time of year, my culture was sent up here. This is how they began to work with the cultures that had been first isolated in Peoria.

Q: And did you send those cultures to other projects?

RAPER: Oh, yes. Yes, we did.

Q: So everybody would start working on them.

RAPER: It was a big cooperative program. There was no secrecy about the penicillin. It wasn’t like some other war projects. This was nice, humane work and everybody could get in on it. The two people over in botany, Professor Stauffer and Backus, took the molds that we had isolated in Peoria, it was then the highest yielding strain known, they took it—and well, first of all it had been exposed to X-ray in another laboratory at the Carnegie Institution in Cold Spring Harbor and they had gotten a mutant that produced even higher yields and that then became the focus of the group here at Wisconsin. In very short order, Backus and Stauffer, by exposing that mold to ultraviolet light had increased the yield of penicillin still more, substantially more.