Innovative cancer treatment machine: Still made in Wisconsin

Thomas “Rock” Mackie stands with gantries for radiation therapy equipment being assembled at TomoTherapy’s Madison manufacturing facility. Accuray, a California maker of radiation surgery equipment, purchased TomoTherapy in 2011.

When a promising corporate research contract dries up at your university lab, but the medical equipment you are developing still has potential for treating cancer, what do you do?

If you are innovator-entrepreneur Thomas “Rock” Mackie at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and the year is 1997, you raise money, create a business, and embark on the long, rocky road of spinoff and commercialization.

The new business would be called TomoTherapy, and its strategy was to blast tumors with radiation while sparing healthy tissue. The machine would guide treatment with a built-in CT (computed tomography) imager to ensure that the tumor sat precisely in the crosshairs of a radiation beam.

The shape of that beam would change if necessary in fractions of a second. Finally, both the patient and the beam could be moved on the fly. Moving both the beam and the patient couch would create the best angle of attack to maximize damage to the tumor while minimizing damage to healthy tissue.

Moving both the beam and the patient couch would create the best angle of attack to maximize damage to the tumor while minimizing damage to healthy tissue.

Creating the machine and getting Food and Drug Administration approval was neither easy nor quick, but TomoTherapy ranked as one of UW–Madison’s most valuable spinoffs when a California business named Accuray bought the company for $277 million in 2011.

Accuray kept the design and manufacturing in Madison, where it now employs 266 people, because of the deep expertise in the complicated machines that marry radiation beams and CT scans — combined with those massive concrete bunkers needed to block radiation during testing.

Last year, Accuray began assembling its other radiation therapy device, called the “CyberKnife,” in Madison. Especially useful for treating brain tumors, this device obliterates tumors from multiple angles using combinations of pencil-thin radiation beams.

The heart of the TomoTherapy invention is a beam-shaping system that clicks like an antique calliope in a testing room, as air pressure instantly opens and closes tungsten “leaves” that block X-rays and shape the beam as needed for more exact targeting.

All of these activities require a serious investment of computer power; the machine comes standard with a rack of computers.

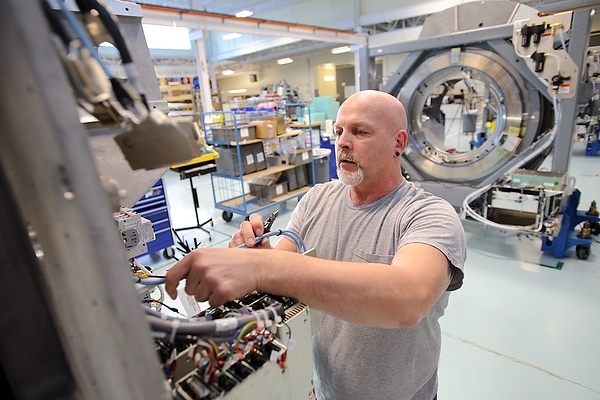

Assembly technician Ken Harlson installs electrical components on a medical radiation therapy unit being assembled at TomoTherapy’s manufacturing facility.

Inventor Mackie, now professor emeritus, says that when the idea of using CT to guide beam therapy surfaced in his research group in 1988, “even we did not believe it could work, but eventually we proved it to ourselves.”

He says the university signed a research contract with GE Medical in 1994, but in 1997, GE decided to get out of radiation therapy. “We had about 20 people in the group, and my business partner Paul Reckwerdt and I started TomoTherapy to save them from getting laid off, and to realize the medical potential of a more accurate radiation therapy machine for treating cancer.”

The smooth white housing of a TomoTherapy machine hides a wealth of complexity in the equipment that converts electricity into X-rays, shapes the beam, registers a CT scan, and moves both the rotating ring that generates the beam and also the patient couch into the optimum position. The ability to fire the beam from any angle makes it easier to hit the tumor while sparing healthy tissue.

TomoTherapy ranked as one of UW–Madison’s most valuable spinoffs when a California business named Accuray bought the company for $277 million in 2011.

Robert Zahn, now Accuray’s vice president of global manufacturing, ran manufacturing for TomoTherapy prior to the acquisition. He says TomoTherapy is the only radiation therapy device that simultaneously moves the delivery system and the patient.

More than 35 countries have received Tomo machines; flags hanging from a wall in the factory are testament to those international sales.

Tomo is one of many successful spinoffs from the broad and deep engagement between the physical sciences and medicine at UW–Madison. For example, the Lunar brand osteoporosis scanners now made by GE were invented in Madison by medical physics Professor Richard Mazess in the 1970s. Mazess formed Lunar Corp. in 1981, and the company was sold to GE in 2000 for $150 million.

Making 10,000-pound TomoTherapy machines that control X-rays with high precision is a heavy responsibility, Zahn says. “We make high-complexity, high-dollar equipment. In more recent years, especially in sites where TomoTherapy is the only device, it’s really been proving itself as an all-purpose, workhorse radiation therapy machine. The most important thing is to make sure the quality is right and that we deliver to the customer on time.”

A major challenge is to ensure a steady flow of parts — ranging from heavy-duty drive chains to valves, vacuum pumps and powerful computer servers — is ready when needed, he says. “We don’t machine anything. We don’t make components. We buy, assemble and test.”

And then test again. After the assemblers spend 12 days building one Tomo machine, Zahn says, “the testers spend another 12 days proving that it does exactly what it needs to do.”