Grass and shrublands burn more land and homes than forest fires

High winds fueled wildfires that tore across open grasslands and through homes in Superior, Colorado, in 2021. Over 500 homes were destroyed. Photo by iStock

When people think of wildfires, they often think of huge forests burning and flames jumping from tree to tree. But according to new research led by Volker Radeloff, a professor of forest and wildlife ecology at University of Wisconsin–Madison, in the United States, the largest areas near humans burned by wildfires are grass and shrublands, not forests.

The study was published in the journal Science recently.

Radeloff has studied the areas where people and wildlands meet for years. Known as the Wildland Urban Interface, or WUI, these areas cover about 10% of land in the United States but are home to about one-third of the population. The WUI (pronounced “woo-ee”) was initially a tool used by the U.S. Forest Service to assist with wildfire management in the western U.S.

The WUI can consist of a wide range of wildland vegetation such as trees, shrubs, grasses, wetland plants, mangroves, moss and lichen. Each type of vegetation requires different management techniques, as they regenerate after fire differently and are affected by environmental factors like precipitation in unique ways.

As Radeloff explains, many people enjoy living in these places because they like to be near the amenities of nature. But these areas are also hot spots for environmental conflicts like wildfires, the spread of diseases from animals, habitat fragmentation and loss of biodiversity.

In regions with growing populations, such as the American sunbelt, more human development is expanding the WUI. Add to that a changing climate with warmer, drier conditions, and the likelihood rises that wildfires will affect humans more frequently.

“Texas is now the state with the largest increase in the number of WUI houses. California had that distinction for a long time,” Radeloff says.

While the total area burned by grass and shrubland fires is much larger than forest fires, grass and shrublands are also much more widespread than forests. They burn and move faster than forests, meaning grassland fires can spread to a larger number of homes than a forest fire might.

Using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and NASA, and with support from the U.S. Forest Service, Radeloff and his team built data sets that show where wildfires burned homes and indicate if those homes were rebuilt.

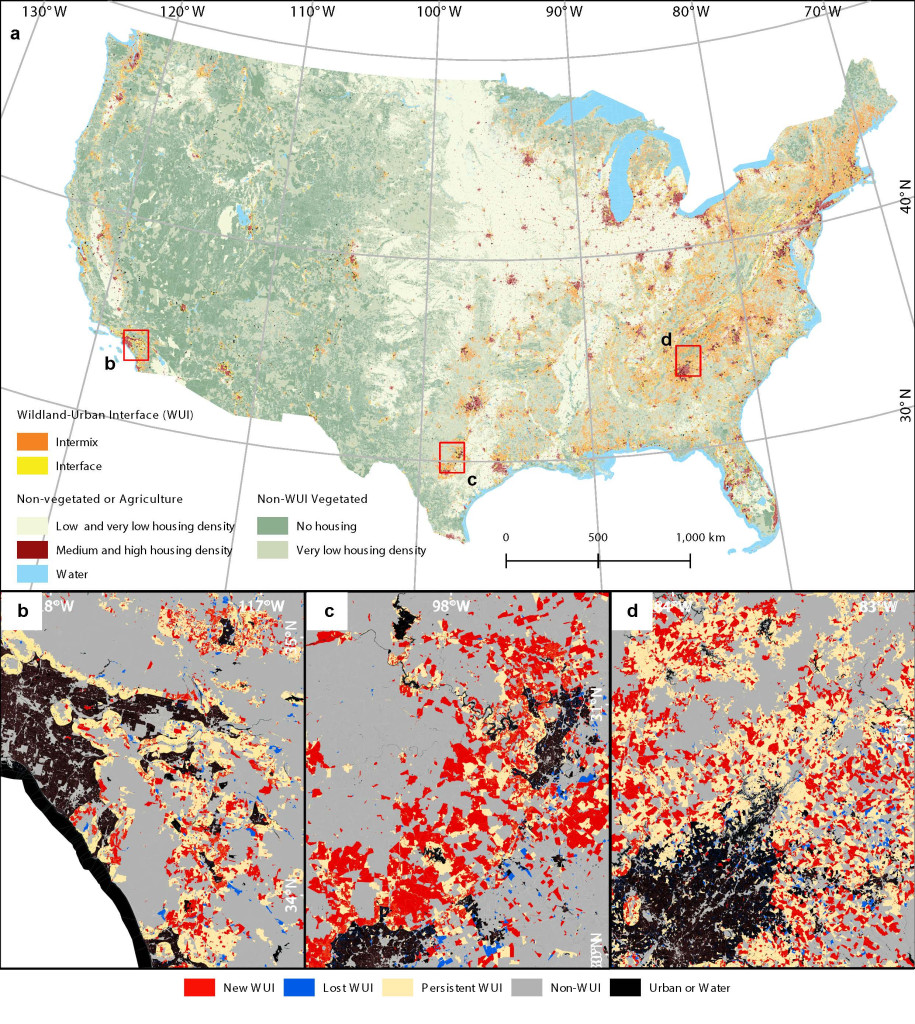

The wildland-urban interface (WUI) in 2020 across the conterminous US, and changes in WUI area from 1990 to 2020 near Los Angeles (a), San Antonio (b), and Atlanta (c). Image courtesy of Volker Radeloff

The researchers found that the risk of wildfire in any kind of WUI vegetation is not deterring the development and rebuilding of homes in areas that have burned in the past.

That’s especially concerning for homes in grassland and shrubland because the vegetation, which can become fuel for fire, recovers much more quickly than a forest would. That means there’s more fuel for a fire to burn again in the same grass and shrubland area more frequently.

The issue is not a lack of homeowner knowledge, Radeloff explains. People who choose to live in these areas often know the risk of fire exists, he says, but it’s a risk they’re willing to take. Whether they feel a connection to the land, a desire to live near a beautiful vista or choose to rebuild in a location that already has electricity and plumbing running to it, people still choose to live in areas at risk of burning.

“It is usually much easier to stay in the same place to build a house,” Radeloff says. “Getting houses rebuilt, businesses reestablished quickly, is important. So, to just pack up and go is really hard for a community to do and happens quite rarely.”

There are ways homeowners can harden their homes against fire, though, and Radeloff believes learning from the homes that don’t burn would be a step in the right direction for people that choose to rebuild after a fire.

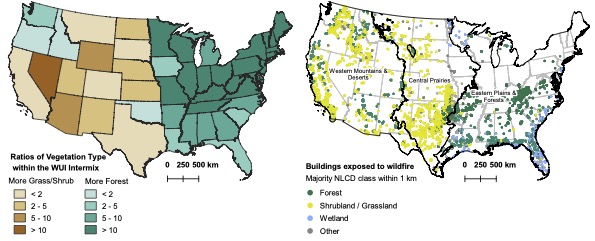

The map on the left compares grassland to forest land in states across the US. On the right, is a map that indicates buildings exposed to wildfire organized by the kind of WUI vegetation across the United States. Image courtesy of Volker Radeloff

However, Radeloff says this burden shouldn’t be entirely on the homeowner. He believes there is room for policymakers to influence how prepared a community is and where zoning should allow new housing developments.

“As a country, we’ve learned not to build extensively in floodplains. We should do something similar for wildfires as well,” he says.

Helping various policymakers at all levels of government understand the difference between how grasslands and forests burn differently, or that different vegetation types all require different management approaches, could help inform better policy.

Ensuring that a community at risk has an established evacuation plan and a clear notification system for evacuation is another area for improvement Radeloff sees, especially in places where these wildfires are more likely to increase. He says that a better notification system and evacuation plans could have helped reduce the toll of the recent fires that burned the town of Lahaina in Hawaii.

“That doesn’t stop the loss of homes, but it stops the loss of life,” he says.

As the world continues to warm, understanding the expanding areas where humans and wildlands meet will be increasingly important. Using data sets like those Radeloff and his team produced can help homeowners and policymakers know what risks may be coming and where how they can better prepare for them.