Student to student: A reunion of ‘60s activists from Madison imparts lessons to millennials about achieving change

UW alumni Andy Mirer (left) and Suzanne Korey (center) take to the dance floor in the Memorial Union during Madison Reunion, which took place from June 14-17, 2018. The reunion featured a variety of entertainment events and panel discussions for UW alumni that attended during the 1960s. (Photo by Bryce Richter / UW–Madison) Photo: Bryce Richter

Parker Schorr, a student writer for University Communications, attended last month’s Madison Reunion and shares his reflections on how students’ experiences during the 1960s can have meaning for students today.

For three days in June, hundreds of aging radicals, activists and former University of Wisconsin students returned to Madison – once a “cradle of counterculture” – to relive the 1960s through a mix of music, art, politics and history.

But the reunion, which was organized by alumni, turned into something more fascinating than simply a cultural Woodstock for ‘60s counterculture. Coinciding with a political and economic reality discordant with the ideals of the ‘60s, the reunion was also a snapshot of a cohort of idealists trying to understand how the America they thought they had secured in their youths had slipped through their fingers.

As the youngest attendee of the reunion by decades and a current student at UW, I received a thrilling crash course in effective political organizing and a picture of a much different time for activism.

There is likely no better generation to advise my generation on how to achieve change, than the one that filled the halls and auditoriums of Memorial Union for three days. They helped to end the Vietnam War, establish the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and institute an entirely new department on campus – the Afro-American Studies department.

What can these activists teach our millennial generation? That nonviolent resistance is still the route forward. The basic principles – symbolic protest and civil disobedience – were flexible enough to counter wars, racism, and repressive authoritarian governments. A resurgence in nonviolent action, like the teen-led movement for gun reform and the #MeToo Movement, are both promising takes on an age-old framework, in their view.

The tenor of the reunion was a mixture of optimism and despair, reverie and regret, passion and anger. Above all, the auditoriums, typically filled to capacity, buzzed with nervous excitement.

At a slideshow of the ‘60s presented by historian Stuart Levitan, attendees seemed immersed in flashbacks. At a black and white photo of a protest, the crowd exploded in applause, and at a photo of two students holding a Confederate flag outside of buses headed to the South on freedom rides, many jeered. The woman with a purple tint to her gray hair seated next to me would jab her husband in the side at each photo and say, “remember that,” and, “we were there.” A photo of Mayor Paul Soglin being challenged by a police officer garnered laughter and applause, partly because he has become an icon of Madison’s ‘60s activism and partly because he sat in the crowd, reliving these formative times with his friends and peers.

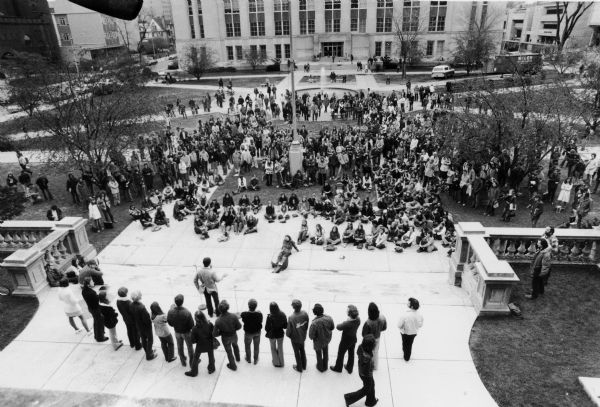

Elevated view of a student protest on the Library Mall in the 1960s. CREDIT: Wisconsin Historical Society

At most panels, the present eventually forced itself into the conversation. The slideshow ended with a rousing speech by Roberta Gassman, former Deputy Assistant Secretary for Employment and Training under President Barack Obama.

“What we have to do, I think, and this conference is an important time to process and look at this, is to stand on the shoulders of the ‘60s activists, to be inspired by the women who are now speaking out, by the young people who are using their voices and running for office,” Gassman said.

“Now is the time for activism,” she added. “A lot is on the line. We must support the next generation in taking the lessons of the ‘60s forward.”

I talked with some of the panelists to try to determine what these lessons were and what the current state of activism is.

Social movements can create change

Gerald Lenoir, a participant in the Black Students Strike that secured the Afro-American Studies Department after a year of negotiations, organizing and eventually a strike, said his time in Madison was formative.

“My experience in Madison is the reason why I’m still a social justice activist today,” he said. “For the first time in my life I recognized how mass social movements change policies, change laws, change attitudes, change hearts and minds.”

He moved to Madison from Los Angeles in 1966, already “radicalized” by the Black Power and Civil Rights movements but yet to participate in mass protests. A friend started taking him to meetings where black and white students formulated 13 demands to university administration, including a program to bring 500 black students to campus, the creation of a Black Studies department run by black faculty and support for a black cultural center.

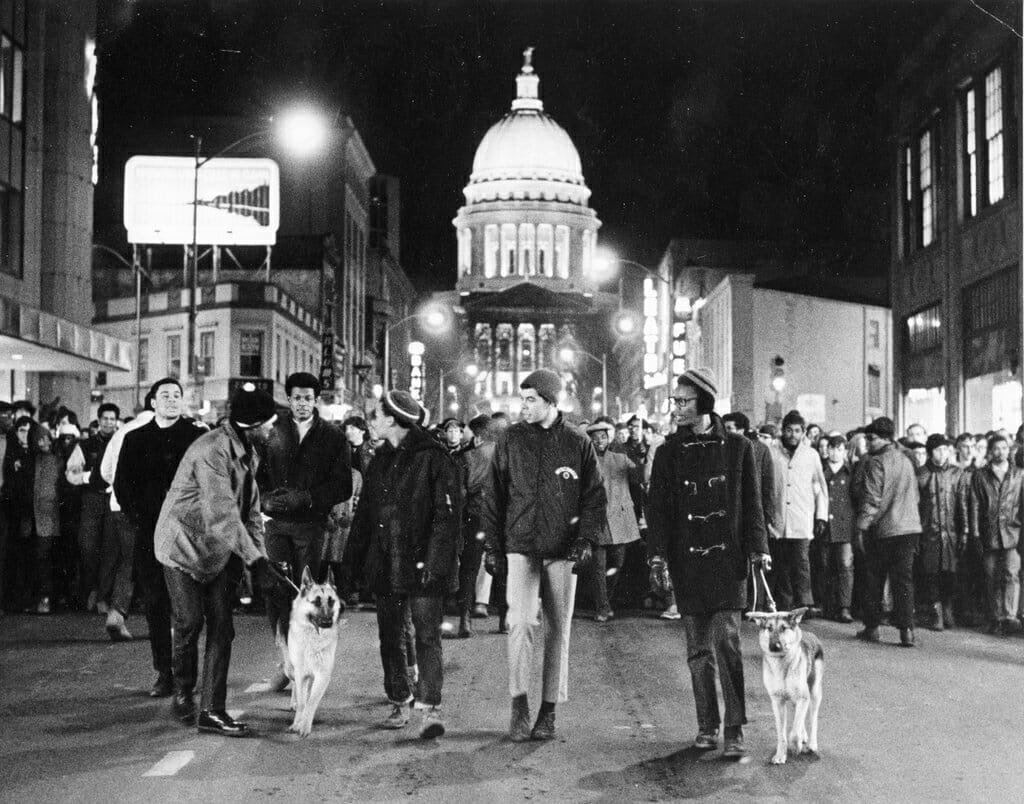

When administration refused, 1,500 black and white students went on strike, disrupting campus and blocking the entrances to campus buildings by linking arms. In response, the governor called in 1,000 National Guardsmen. The protests then escalated: on Feb. 13, 1969, 20 black students linking arms led a crowd of at least 7,000 students to the Capitol. The university soon conceded.

University of Wisconsin students march in support of African-American students’ rights, February 14, 1969.

“We couldn’t have won the struggle without white allies,” he said. “That was the lesson for the ages, that no struggle can be made without allies. And so part of our struggle as black people is to do the outreach and the alliance building with other social movements and with other communities and recognizing that racism doesn’t just impact black people, it impacts all of us in one way or another.”

Lenoir majored in business but continued as an activist after he graduated and left Madison in ‘70. He would become a leader of the anti-apartheid movement around South African oppression in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s in Seattle and the San Francisco Bay area; the director of the San Francisco Black Coalition on AIDS during the height of the epidemic; and for eight years he was the founding director for the Black Alliance for Just Immigration before he joined the Haas Institute at UC Berkeley, a social justice think tank.

He has also spent the past 20 to 30 years grooming a new generation of activist leadership. He mentored Opal Tometi, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, and said he was encouraged by the number of social movements coming alive in the 21st century.

“We saw a similar thing in the ‘60s with the rise of the Civil Rights and the Black Power movements,” he said. “We saw other movements come into the fold. It gives me hope that some of these movements are beginning to cohere and build stronger alliances to look at how we can change people’s hearts and minds.”

I asked him how to not get discouraged when a movement seems as if it’s been derailed. My generation is savvy and intelligent, but I get the sense that many of us lack an understanding of how power can exist and have influence outside of electoral politics. And with a political system which sometimes feels rigged against the young, the poor and minorities, electoral politics often feels hopeless.

When we learn of the Civil Rights movement and of nonviolent protest early on, it’s taught almost purely as a historic exercise and not a practical one. We have spent our whole lives in a political and social atmosphere that favors charisma over ideology, and which is suffused with apathy – as evidenced by low voter turnout.

Lenoir said it’s best to take the long view.

“The Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power movement didn’t gain traction for decades,” he said. “People have this in their minds that the Civil Rights Movement started in 1955 with the Montgomery Bus Boycott. But a decade before that there were activists in the South doing freedom rides and getting arrested.”

“Social change doesn’t happen overnight,” he added. “Social change doesn’t happen just because you had a series of demonstrations over three or four years. There has to be mass pressure over decades.”

Madison had an ‘ambiance’

Alan Ruff hitchhiked to Madison from Boulder, Colorado, across the Great Plains in ‘74 and has been an activist in Madison ever since. He said State Street, where currently stands Wendy’s and vape shops and high-end apartment complexes, was once a hub of culture, with kiosks up and down the street plastered with hand-made posters and political advertising.

“There was an ambiance here – a political, cultural scene that certainly did not exist in a place like Boulder or anyplace else I was familiar with at this point,” Ruff said.

View up State Street towards the Wisconsin State Capitol taken from the West Johnson Street intersection in 1957. Businesses include the Orpheum Theater, Arenz, and Ward’s. CREDIT: Wisconsin Historical Society

Now, though, he said the world is like an “accelerating locomotive belching smoke,” propelled down the tracks by a political economy – capitalism – which offers no solutions to the problems it has created. Suffice to say, he is not optimistic about America’s future.

“What I see right in front of us that few people are considering is the fact that what we currently are living in a world that can offer up no solutions to what I term the “Big T-bone Collision” that we’re headed towards … the environmental crisis that is right before all of us,” he said. “When that comes – its already underway in good parts of the world – it’s going to exacerbate conditions all over the place which will lead to attempts to reform, attempts to protest and social dislocations unimaginable before us.”

Like most of the older radicals I talked with, however, his “informed pessimism” is countered slightly by his experience as an anti-war activist. For a small group of people to stand up to America’s military and win, likely serves as a vote of confidence for the power of the masses.

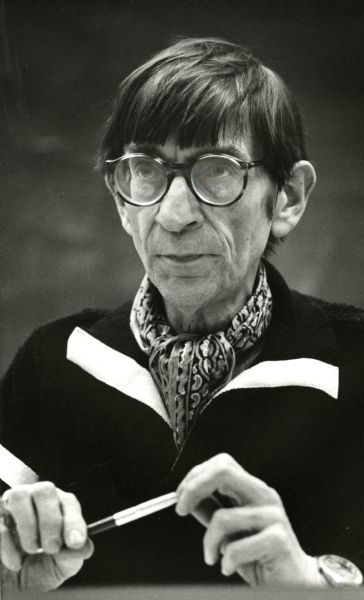

Harvey Goldberg, teacher, historian and political activist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. CREDIT: Wisconsin Historical Society.

He said his mentor and professor at UW–Madison, Harvey Goldberg, an enormously popular orator who would deliver lectures to halls packed to capacity with students not even in his class – taught him that movements flow into one another. The peak of anti-war and student movements was a confluence which gave birth to a whole range of activism, like the early environmental movement, the women’s movement and the Chicano movement, he said.

“One of the things Harvey taught us was that all movements ebb and flow,” he added. “They have peaks, they have valleys, they have victories, they have defeats.”

Too many factions hurt movement

Once Martin Tandler hopped off the bus in Madison from New York in ‘61, he was immediately involved with politics. He started the Campus Americans for Democratic Action on campus, the left wing of the Democratic Party, and was involved with student government. He learned he liked to run things.

After flunking out of Madison – a hard thing to do in those days, he said – he returned to New York. But when the draft board started to pursue him, he returned to Madison and asked the dean to re-admit him so he could get a deferment from the Vietnam War. Fortunately, the dean agreed.

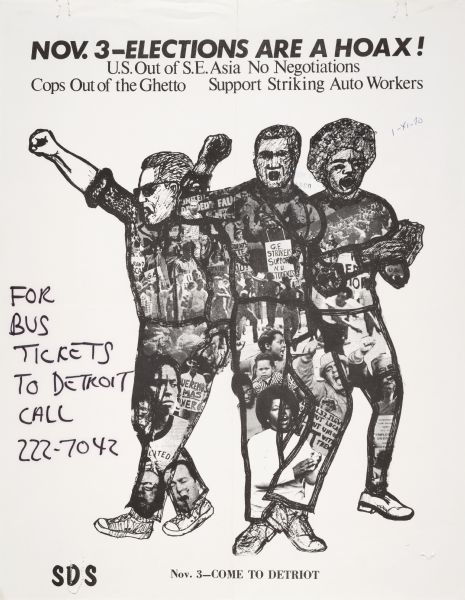

He started the Madison chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, a powerful but short-lived student activist movement, in ‘65. In just seven years, SDS rose to prominence and power in anti-war demonstrations and then disintegrated, largely due to internal politics, and splintered into many different factions – with one faction, the Weather Underground, turning violent.

Like the internal politics of SDS, he said the left in Madison in the ‘60s was similarly disjointed.

“If there were 10,000 people involved in the left in Madison at that time, there were 10,000 points of view,” he said. “I don’t have any patience for that. It’s really simple. Do we really want to sit and talk about, ‘are we going to have revolution in one country or revolution in all countries,’ or ‘what do you mean by revolution,’ ‘what do you mean by – ’ or do we just want to end this war in Vietnam.”

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) protest in Detroit, November 3, 1970. CREDIT: Wisconsin Historical Society.

He returned to New York after he graduated. After being fired as a junior high school teacher from four different schools in three years – one time because he took his students to a Vietnam teach-in – he “sold out” in the eyes of his peers and joined his father’s textile industry. He would eventually grow the business to a multimillion dollar operation.

He, too, is not optimistic about the future of America. In his time doing business overseas in China, he said it is clear that China, economically and politically, is ascendant.

“This society is kind of unravelling,” he said. “There’s no community. It’s of concern to me. In the big sense I see the gradual power shifting from this country. I think this is an empire in decline. These are the last paroxysms of a death knell, and China is going to be running this planet in 20, 30, 40 years. And I’ve been there, and I’ve done a lot of business there, and you can see why: they’re organized and they’re structured.”

Conversely, America is unorganized, especially politically. He said the Democratic Party lacks a coherent, unified vision, fails to articulate its ideology and has let the Republicans dictate the framework that government is bad.

“How is it that the ‘left’ of the democratic party, as epitomized by Bernie Sanders, has an identical trade policy as Donald Trump?” he posed as an example of their incoherence.

Oddly, perhaps, many in my generation adore Bernie Sanders. The reason for this, in my view, is that he spoke intelligibly about a word that no other politician liked to touch: class. Although Sanders’ understanding of trade policy and the intersection of race and class are lacking, he is a politician who seems to rest on values and is therefore a hopeful figure for a generation that has only known equivocating politicians who rely on charisma, mega-donors and name recognition at the expense of ideology.

Students today have less leisure, work harder

At the Radical Perspectives Teach-In – a free, more radical “sister” event to the Madison Reunion held at Union South – aging and young radicals joined to strategize on what comes next.

David Williams, a co-organizer of the event and an active Madison radical since the ‘60s, was primarily an anti-war activist in his time at the UW. He said students today have a tougher time mobilizing and sustaining mass movements despite modern technology that makes those two things easier.

“I kind of skated through four years as a liberal arts major without having to apply myself that much,” he said. “I mostly majored in activism. These kids today, I get the impression they are in very specialized disciplines, majors – and they’re having to work a lot harder. There isn’t as much leisure.”

He said successful political action always comes back to direct action, and direct action almost always works best if it’s nonviolent struggle.

“I was part of antiwar movement that had a different strategy,” he said. “What we believed was we couldn’t fight the U.S. government on our own, small bands of radicals fighting the U.S. government. The Weathermen tried that and it was a fiasco. We felt that if you spread the antiwar sentiment to all layers of American society, eventually Nixon would have to get out of Vietnam. And that’s pretty much what happened.”

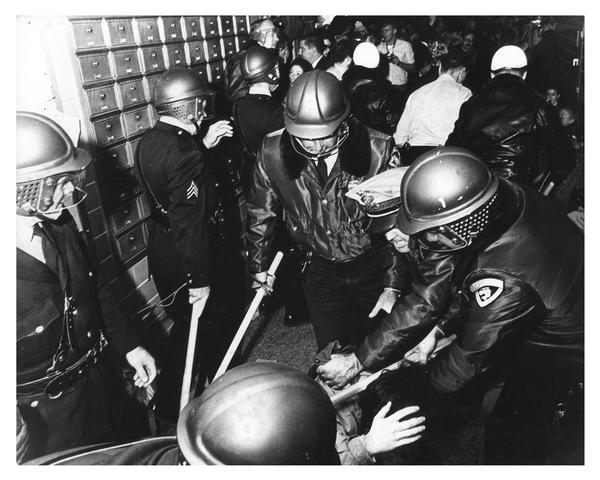

Police clash with students during campus demonstration to protest Dow Chemical involvement in the Vietnam conflict. Here, several police officers with clubs hold a student down on the floor. CREDIT: Wisconsin Historical Society.

Williams said there’s a certain reason for cynicism among older radicals. While some of the high hopes of the ‘60s have been realized, others have been lost and crushed in the rightward shift of the nation’s politics. But, as a member of the Gray Panthers, a network of local, multi-generational advocacy groups, he said the old cannot give up.

“Older people – former ‘60s activists – we seniors still have an important role to play,” he said. “The corporate plutocrat and the right wing, they are going to come after social security, medicare and medicaid, and they’re going to do everything they can to trash the public safety net. I think that what we older activists is to continue to be activists and form a common front with millenials.”

“We all face these horrific environmental and climate change problems,” he continued. “We cannot give up. Giving up is not an option because if we give up, we’re really going to get our asses kicked – all of us. An injury to one is an injury to all.”