A curtain call for impresario, tireless advocate for science literacy — Shakhashiri retires

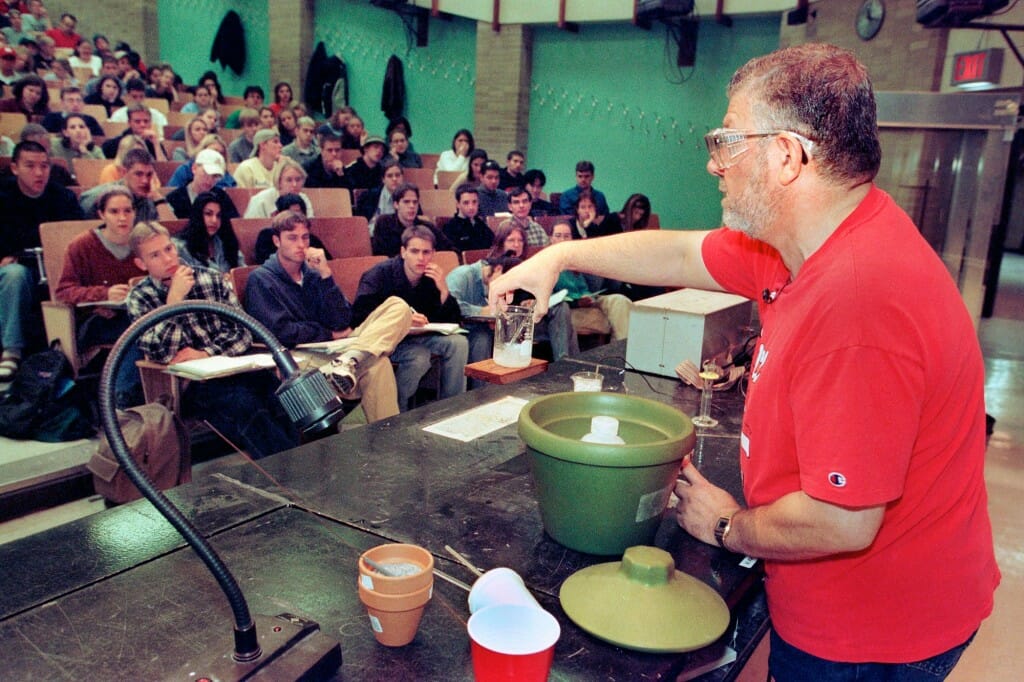

Bassam Shakhashiri, the kinetic and tireless science educator and 81-year-old University of Wisconsin–Madison chemistry professor who for more than 50 years charmed and amazed audiences with the wonders of science, has retired. His steadfast advocacy for science literacy was a clarion call to scientists and politicians alike.

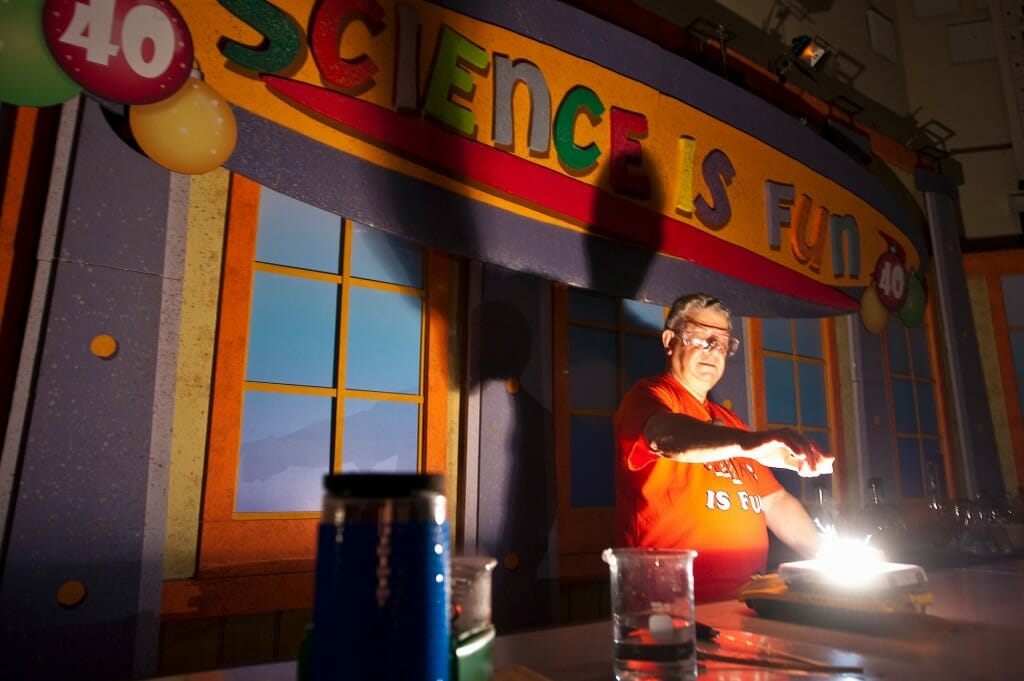

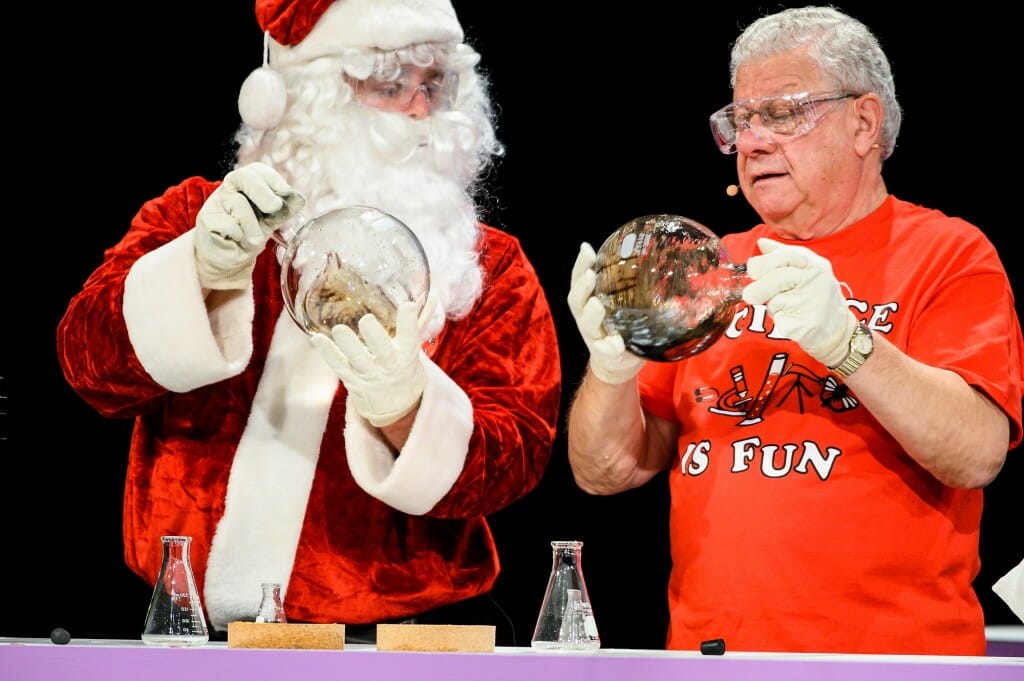

Best known for his colorful (and sometimes loud) public demonstrations of chemical phenomena, Shakhashiri played to packed houses from Washington to Silicon Valley. His annual program, “Once Upon a Christmas Cheery in the Lab of Shakhashiri,” was a staple in Madison, on public television, and — while serving in the late 1980s as an assistant director of the National Science Foundation (NSF) — in the halls of Congress and venues such as the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and the National Academy of Sciences.

Bassam Shakhashiri

The goal was always the same: to convey to audiences — by power of demonstration — the value of science to society and the absolute necessity of broad science literacy for understanding everything from human health to climate change.

“Science is a way of looking at the world,” says Shakhashiri. “Science literacy is the appreciation of science without a deep understanding of chemistry, physics, biology or any other science. It’s an attitude.”

Shakhashiri emigrated from Lebanon to the United States at the age of 17 with his parents and two sisters. He joined the UW–Madison chemistry faculty in 1970, arriving on campus one week after the Sterling Hall bombing.

Channeling a desire to reinvigorate the college learning experience, he became the founding director of the UW System Undergraduate Teaching Improvement Council in 1977. In 1983, he founded the UW–Madison Institute for Chemical Education, a nationally recognized center that provides support, tools and inspiration for science educators. ICE has been a leader in helping revitalize science curricula in the nation’s schools.

“I wanted to help put Wisconsin on the map in science education,” Shakhashiri recalled in an interview in an aerie of an office overlooking Lake Mendota. “Wisconsin was very attractive to me. I learned the meaning of the Wisconsin Idea. I feel it in my bones. I cherish the freedom of scholarly work and public service.”

In 1984, Shakhashiri accepted an appointment to serve as NSF assistant director for science and engineering education. He immediately set out to rebuild a program whose budgets were, for all practical purposes, zeroed out by the Reagan administration, leaving only $16 million in 1981 for graduate fellowships that had already been awarded.

Read a Q&A with Bassam Shakhashiri

With the support of scientists, an energetic flair, and a knack for getting the ear and sympathy of Congressional leaders, budgets for science education at NSF surged to the $230 million mark by 1990. However, around that time, Shakhashiri was forced from the agency, in large measure because his success at rekindling Congressional support for science education was viewed by some as a detraction from the agency’s research mission, he says.

In some quarters, 20 percent of the NSF budget pie was too much: “I wanted to make the pie bigger,” recalls Shakhashiri. “I always advocated for the agency.”

Today, NSF’s science education budgets stand at more than $900 million. In 2007, the National Science Board, which oversees NSF, conferred on Shakhashiri its Public Service Award, an act viewed by some as vindication for the Wisconsin chemistry professor and his uncompromising advocacy.

Returning to Madison, Shakhashiri established himself as a preeminent scholar in science education, over time giving more than 1,500 invited presentations in the United States and around the world.

With collaborators, Shakhashiri authored a five-volume series of chemistry demonstration handbooks, published by UW Press and described as “classics, used year in and year out” by teachers and others to illustrate meaningful lessons in science. The books remain “the best such tools for teachers in any language ever written,” extolls Cornell chemistry professor and Nobel Laureate Roald Hoffmann.

In 2001, Shakhashiri was named the first William T. Evjue Distinguished Chair for the Wisconsin Idea, a position he held for 20 years.

“He is a force of nature who is now a legend, especially for his Christmas lectures,” says Sean B. Carroll, a UW–Madison emeritus professor of genetics who serves as vice president for science education at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “His cleverness, his boundless enthusiasm, and his showmanship no doubt inspired many future scientists and teachers.”

To Shakhashiri, “science is fun.” He wears the mantra like a uniform, invariably sporting it on a big blue button or a cardinal tee shirt. He is known to dispense the buttons — to everyone from kindergartners to cab drivers — at so much as a smile. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Shakhashiri and his students could be seen tooling around Wisconsin and beyond in a “Science is Fun” box truck, fostering learning and curiosity in schools, shopping malls and community centers.

“I saw Bassam’s demonstrations first perhaps 50 years ago, and loved them,” says Hoffmann, a theoretician by trade, whose play about the nature of discovery, “Oxygen,” was co-authored with UW alumnus Carl Djerassi and produced in Madison with a memorable assist from Shakhashiri. “The public demonstrations in the play were not done in any other production,” recalls Hoffmann, clearly touched by the painstaking effort Shakhashiri poured into the play.

In 2002, Shakhashiri established the Wisconsin Initiative for Science Literacy, a program he will continue to lead. As its name implies, WISL ‘s mission is to promote literacy among the public in science, mathematics and technology “to attract future generations to careers in research, teaching and public service,” and to help UW–Madison graduate students master the communication skills required to effectively share their research with non-experts.

In 2012, Shakhashiri served as president of the American Chemical Society, one of the world’s largest scientific organizations with 155,00 members in 150 countries.

“You can’t pigeonhole Bassam,” says Cora Marrett, the UW–Madison emeritus sociology professor who followed Bassam to leadership roles at NSF, including twice as acting director and a tour leading the agency’s education efforts, the same role Shakhashiri defined more than 30 years ago.

Among his accomplishments at NSF, she notes, was being an early advocate for inclusion in science, reaching out to underrepresented populations, including women and people of color.

“It was an emphasis he retained over the years,” says Marrett. “It was a deep commitment” to help enable untapped pools of talent to contribute to the enterprise of discovery and, ultimately, society.

Shakhashiri’s retirement marks the end of some of the Wisconsin chemist’s public engagement activities, including his famous Christmas program, but he says his commitment to public service in the interest of broad science education and literacy is unwavering. “I will continue to live the Wisconsin Idea.”