21st century medicine helps Amish deal with rare, inherited illnesses

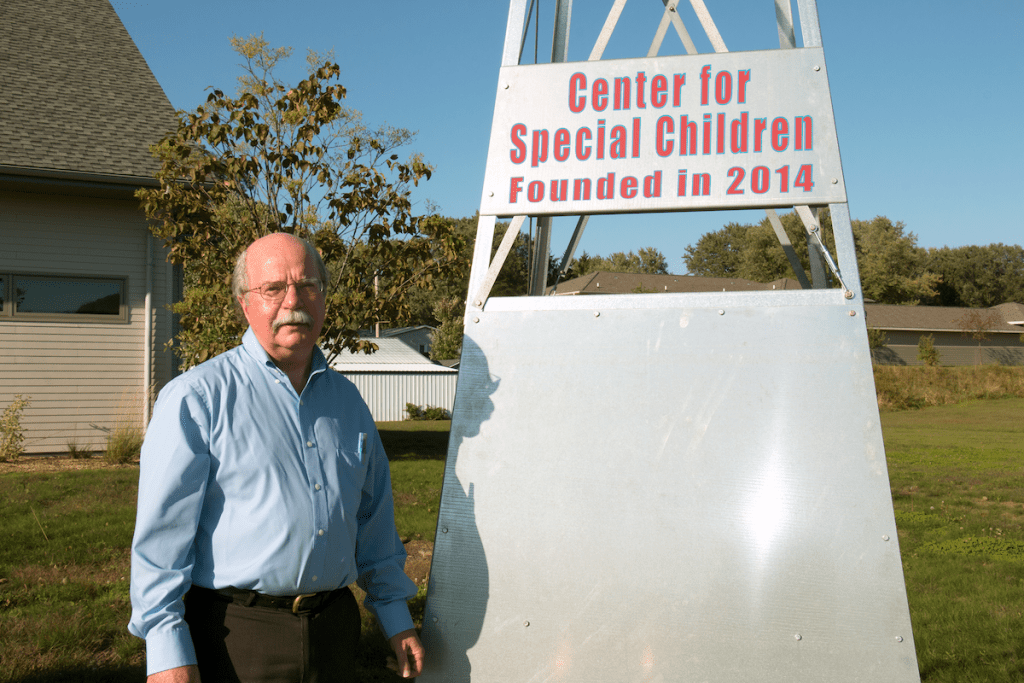

James DeLine founded the Center for Special Children in La Farge to attend to the particular health needs of the Amish and Old Order Mennonite families in Wisconsin. The Center exists within the La Farge Medical Clinic, also started by DeLine, which is part of Vernon Memorial Health Care. Photo by David Tenenbaum

Editor’s note: A recent article in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported on Dr. James DeLine’s work with the Wisconsin Amish community. This story describes how UW–Madison and the Wisconsin Partnership Program are helping the effort.

LA FARGE, Wisconsin – There is no car in the driveway, neither phone nor electricity in the house. Handmade clothes dry on the line.

It’s fall 2018, and La Farge physician James DeLine has brought us to talk with Barbara and Daniel Hochstetler, part of the large Amish population in Wisconsin’s Driftless Region.

Six of their 11 children live with siterosterolemia, an extremely rare disease that can cause joint damage, stroke or heart attack, due to accumulations of a plant-based fat akin to cholesterol.

DeLine has practiced family medicine in La Farge since 1983. In 2015 he started the Center for Special Children to care for Wisconsin’s large concentration of Amish or Old Order Mennonite people.

Rural doctors pride themselves on being able to treat a wide range of conditions in their patients, but DeLine’s practice brings him face to face with several rare genetic conditions that were present when the Amish and Mennonites immigrated from Europe to America and then Wisconsin.

And that, in turn, has brought DeLine into a close collaboration with specialists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who have developed tests, and suggested treatments, for some of those conditions, including siterosterolemia.

Amish and Mennonite families avoid technologies that, they feel, would endanger the social cohesion that is key to their survival. Thus they do not own motor vehicles or use telephones or electricity in the home. Photo by David Tenenbaum

In quiet voices, DeLine and the Hochstetler parents recounted how they learned that the family carried a gene for the rare disease. Years previously, their son, Perry, had been seen at the La Farge clinic with painful arthritis and large lumps in his limbs. “Later, when we discovered that a relative of his mother had sitosterolemia,” DeLine explained, “we thought back to this young man and with some searching, we found him, had gene testing done at UW–Madison, and discovered that he too had the disease.”

After starting medicine and changing his diet, Perry’s elbow lumps began melting away, DeLine said. “He has had no further arthritis, and his exercise tolerance has improved.”

Eventually, with genetic testing at UW–Madison, the mutation was diagnosed in six of the 11 Hochstetler children. Only then did Daniel volunteer that he had heart pain (likely just “age catching up with me”) during heavy exertion, was actually caused by a buildup of plaque in his heart arteries. After starting the same drug as his children, Daniel has improved, though he said he can “still feel it once in a while if I exert myself.”

In the tradition of family doctoring

DeLine has become an expert in the culture, family relationships, and medical needs of the Amish and Old Order Mennonites (sometimes called the “Plain” people).

Although their acceptance of technology is highly constricted by culture and religion, the Plain benefit from DeLine’s hybrid of 19th century rural doctoring with 21st century genetic medicine.

Chris Seroogy, professor of pediatrics at UW–Madison, is a long-time collaborator in the effort to bring 21st century health care to Wisconsin’s Plain populations. Photo by Robert C. Thayer

The genetic work has relied on clinicians from the School of Medicine and Public Health, and on testing at the State Laboratory of Hygiene, both at UW–Madison. The State Lab has already developed fast, low-cost diagnostic tests for more than 30 conditions afflicting Plain populations in Wisconsin.

Vanessa Horner, director of cytogenetic services and molecular genetics at the State Lab, said that once a test has been developed and validated, it becomes a “clinical assay” that must be performed in a certified laboratory such as hers. “It’s a highly regulated, rigorous testing environment.”

Funding for these tests and related activities came from grants totaling $800,000 from the Wisconsin Partnership Program in the School of Medicine and Public Health. “Addressing the health care needs of Wisconsin communities is a priority for the Wisconsin Partnership Program,” said Richard Moss, chair of the partnership education and research committee.

“This team’s innovative and successful community-engaged research has resulted in increased newborn screenings and affordable genetic testing that have the potential to spare our state’s Plain families from fatal medical conditions and costly hospitalizations,” added Moss, senior associate dean for basic research, biotechnology and graduate studies.

One newborn screening test created at UW–Madison, for example, detects maple-syrup urine disease, which prevents the normal breakdown of certain amino acids from food. Then, toxic byproducts attack the brain and other organs immediately after birth.

According to Mei Baker, co-director of newborn screening at the State Laboratory of Hygiene, which developed the test, “We make special arrangements for lab testing beyond regular working hours. The midwife collects a blood sample and a hired driver delivers it immediately to our lab. Six or eight hours after birth, we have the result, and the clinicians at Waisman Center advise the parents on an appropriate formula to avoid the symptoms. This service is free of charge, and you cannot do any better than that.”

This team hauls logs and saw timber at the Hershberger family sawmill outside La Farge, Wisconsin. Photo by David Tenenbaum

Genetic diseases among the Plain arise from “founder mutations” that were present in the few Amish and Old Order Mennonites who immigrated to America in the 19th century. A second “genetic bottleneck” occurred among smaller groups that moved to Wisconsin, starting about a century ago.

Most of the genetic diseases he sees can be treated if not cured, DeLine said.

Mixing old and new

DeLine’s long and deep experience with many Amish families, and his anthropological knowledge of family relationships are part of his doctor’s toolkit.

So are home visits.

“He talks about how helpful it is to see a child in the home environment, surrounded by siblings, grandparents, parents,” said Christine Seroogy, a professor of pediatrics. Seroogy is one of several UW–Madison colleagues who provide outreach clinical services with the Center for Special Children. “It’s been quite an experience, an honor, to take part in those home visits.”

The characteristic homemade clothes of an Amish family hang just inside the back door. Photo by David Tenenbaum

“Home visits were not part of my medical training, but it’s how doctors used to practice, and Jim DeLine still does,” she added.

When Seroogy began working with DeLine in 2007, one focus was severe combined immune deficiency (SCID, or “bubble boy”) disease. Though fatal, SCID can be detected with newborn screening and in some cases treated with bone marrow transplant. Over the years, she has worked closely with DeLine, newborn screening experts at the State Laboratory of Hygiene, and Plain families to improve SCID diagnosis and treatment.

In many cases, a true diagnosis can keep patients out of hospitals and away from physicians who tend to order an endless series of costly tests that cause more trouble than healing.

“When we must deliver news about a child with a lethal disorder,” DeLine said, “if the family knows what’s going on, sad though it is, it’s a gift to the family to take the child home and care for them surrounded by their community and their family.

“It’s hard to treat something you don’t recognize, understand,” DeLine added. “Each time a new condition is identified, the search for a cure can begin.”