Recovering the history of UW’s first African-American students

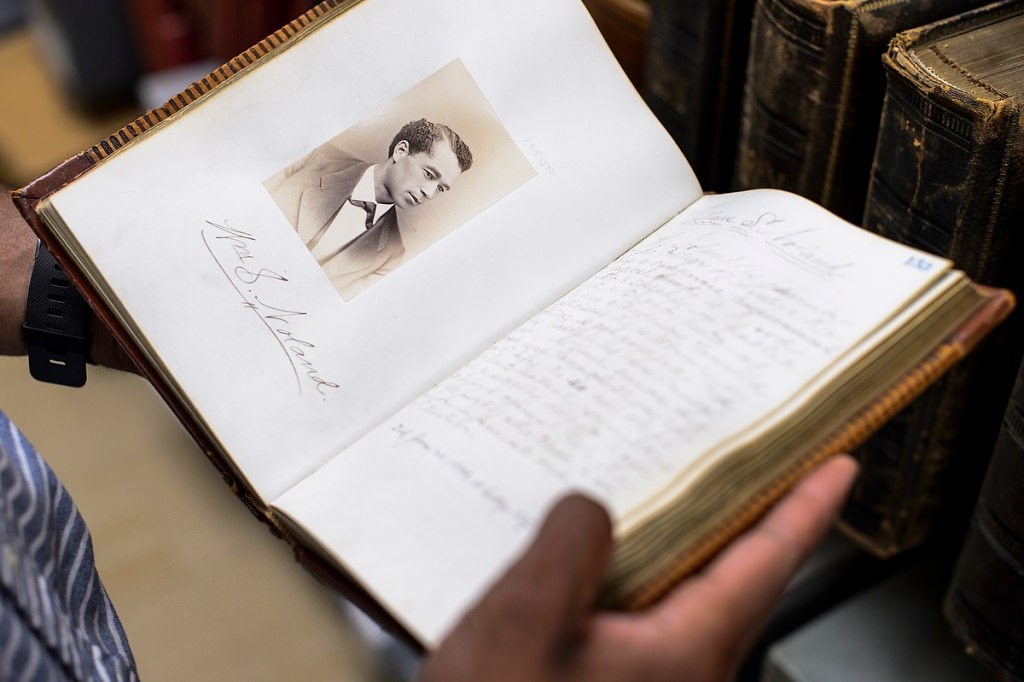

Harvey Long looks at a vintage photo album entry for William Smith Noland, the first African-American student known to have graduated from the University of Wisconsin. Photo: Jeff Miller

They came from across the country, drawn to an educational institution that welcomed them when many others barred the door. They left ready to launch successful careers in law, medicine, academia, journalism and a host of other fields.

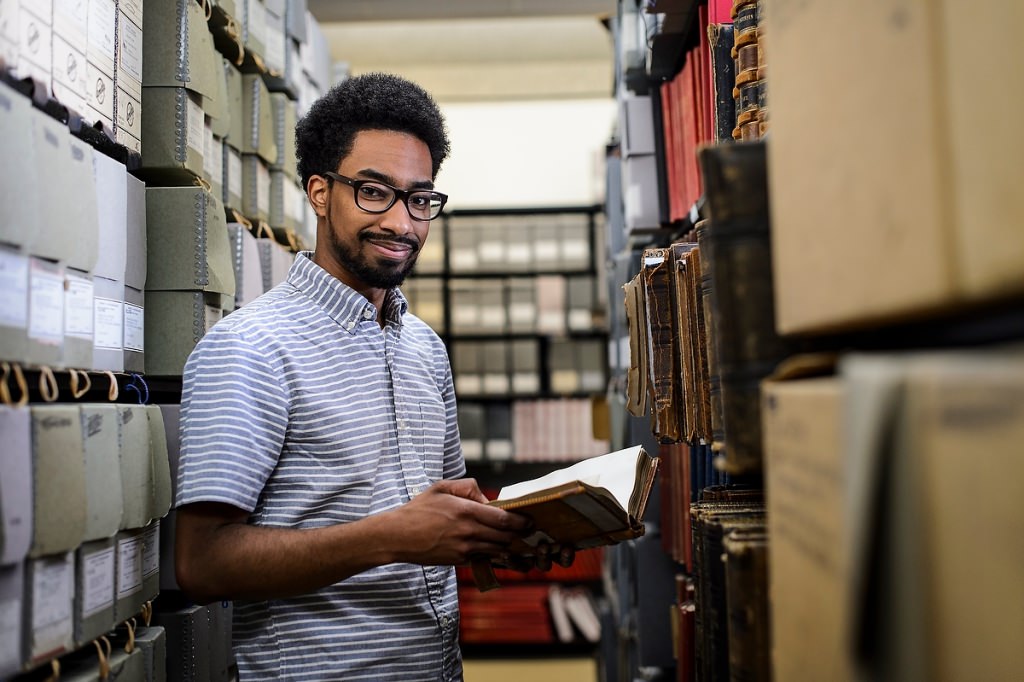

The history of black students at the University of Wisconsin–Madison goes back a lot farther than people think. Harvey Long, a doctoral student in library and information studies, has made it his mission to bring their stories to light.

Long recently completed an archives-based examination of the period between 1875 and 1940.

“I started this project on early African-American students,” he says, “to find out who they were, where they came from, what was their extracurricular activity, what they did after leaving the university. This was something I became interested in once I moved here, because the narrative — that blacks did not come here until the 1960s — was just not right.

Harvey Long looks through University of Wisconsin photo albums from the 1870s and 1880s while doing research at University Archives and Records Management Service in Steenbock Library. Photo: Jeff Miller

“When I told my dad I was going to Wisconsin, he said, ‘You could go to Chapel Hill; black people don’t live in Wisconsin.’ That’s not true, though people think that even here at the university. Black people have been coming to the university for a long time, but it’s a long, complicated history.”

Like Long himself, a native of North Carolina, many of the university’s first black students came from the South. Although some southern states had what were then called “Negro” institutions of widely varying quality, many barred black students from state colleges and universities. “These students came to Wisconsin because this barrier did not exist here,” he says.

Yet although the university was officially more receptive to black students, records show that racism in Madison could make life difficult for the students.

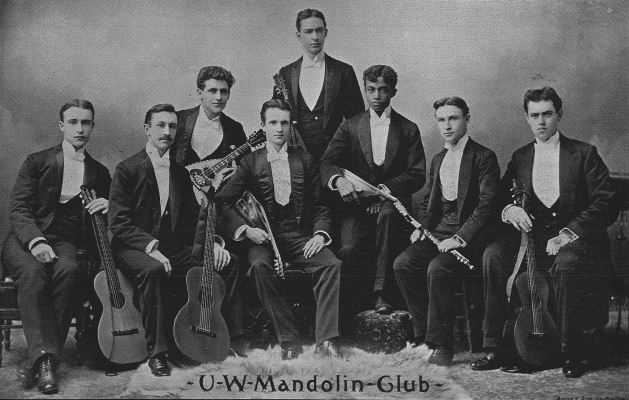

William McCard, an Illinois native who graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1893, is in the third row, second from left. UW-Madison Archives

Long looked at photos in yearbooks to identify students — an admittedly rudimentary search — and then began delving into the UW–Madison archives, newspaper articles and the black press for details. Publications such as the NAACP’s “The Crisis” carried much information about black students graduating from college.

The earliest known black student at UW–Madison was William Noland, who was born in Binghamton, New York. “After graduating in 1875, William entered law school here and stayed for two semesters, then dropped out and moved to Washington, D.C.” Long says. “He committed suicide in the 1890s. Not a lot is known about him.”

Leo Butts, who graduated in 1921 with a degree in pharmacy, was the son of Benjamin Butts (ca 1850-1930), who was born into slavery in Virginia, moved to Richland Center and then Madison, and befriended Robert M. La Follette while working at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin (now Wisconsin Historical Society).

The three Murphy sisters — Ida, Carlita and Frances — came from Baltimore, starting in 1935. The sisters all earned journalism degrees and after returning home, “kept their father’s newspaper, the Baltimore Afro-American, afloat,” Long says. The paper had “a storied history,” he adds, and survives as the website www.afro.com.

Harry McCard, who received a B.S. from the University of Wisconsin in 1896, with fellow members of the Mandolin Club. UW-Madison Archives

In an oral history, Frances Murphy remembered hostility from the house mother at Barnard Hall. “I don’t remember Wisconsin too fondly,” she said. “I remember Wisconsin as being a chore, as something I had to do” to advance her future career in journalism and satisfy her father’s high expectations.

The extensive oral history from Frances Murphy was something of an exception, Long says; the most frustrating part of his long search is the “very spotty” nature of the information. “It can be extremely difficult to fill in the story, the blanks, because black students were such a small population, and the people who are going to be documented are the people who have resources, the students in fraternities, sororities, those who come from well-to-do families. Many of the black students were working their way through college and more concerned with paying the bills.”

The Badger yearbook photo of Freddie Mae Hill, who received a UW home economics degree in 1928. Hill was the daughter of a grocer who moved his family from Atlanta to Madison in 1910.

University archives at predominately white institutions tend to focus on black athletes, he adds, resulting in “stereotypical and problematic narratives, and the silencing of others.”

Some of the southern black students educated in Madison returned to apply their education in their own communities as professors or doctors, Long says. For example, Arnold Hamilton Maloney graduated in 1931 with a Ph.D. in pharmacology. He became a professor and head of the Department of Pharmacology at Howard University from 1931 until his retirement in 1953.

Although most of the students lived in Madison’s small black community, Illinois natives William and Harry McCard lived with Regent Lucien Stanley Hanks, a Connecticut-born banker, in a mansion (since demolished) on Langdon Street. “They had learned barbering and tailoring from their father, and used that to put themselves through college,” Long says. After earning a law degree at Northwestern, William practiced in Illinois and then Baltimore, where Harry became a successful medical doctor.

John Hill operated Hill’s Grocery for 50 years at East Dayton and North Blount streets.

In the early days, black students were more integrated into the campus’s intellectual life than its social life, Long says. “They were often elected to debating or forensic societies, and they distinguished themselves as debaters or orators, but when it came to social life, fraternities, sororities — a lot of the time, they were not offered admittance. In some of the Greek constitutions, it’s clear who can be a member. One said, ‘(We) only accept men of the Aryan race.'”

Now, at a time when demands for greater diversity and inclusion are being heard at UW–Madison, Long says, “I want the university community to understand black students’ long, complicated history at the university. Race played a key role in their isolation from campus activities.”

“The state was receptive, but it wasn’t perfect,” he says. “It’s like you get an invitation to a party, but you might not have the right clothes, or you might not be asked to dance. The University of Wisconsin was not paradise, but it was a step up for many of these students.”