English professor explores the ‘useful and sweet’ in medieval how-to texts

Some people enjoy cookbooks and other “how-to” manuals because they provide guidance in creating real-life masterpieces, bit by bit. Others devour recipes, diagrams and illustrations for pleasure, conjuring fanciful images regardless of whether they will ever come to fruition.

Lisa Cooper, associate professor of English at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, does a little of both. Exploring the proliferation of instructional manuals from the Middle Ages, as well as their relationship to works of medieval literature, she examines both the content and how writers and readers made it personal to their own lives.

“I’m really invested in the pleasures of practical knowledge, in life as in books,” says Cooper. “I relish not only the sense of personal achievement, but also of connection with the world and with other people that they can provide.”

In December, the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded Cooper a 2016-17 fellowship. With the fellowship, as well as support from the College of Letters & Science and the Graduate School, Cooper will spend the next academic year completing her book-length study Ars Vivendi: The Poetics of Practicality in Late Medieval England.

These days, many instructional documents forego beauty for simplicity without elegance, or mere efficiency. Works from the Middle Ages show that aesthetic and technically precise information can not only exist side by side but enrich each other.

“Medieval authors, such as Geoffrey Chaucer, tell us that fiction in this period was held to a standard of being both utile et dulce, useful and sweet,” says Cooper. “Literature was defined, in part, by its capacity to do something useful for its readers, something that went beyond providing mere entertainment.”

Cooper’s project argues that the flip side is also true: that even instructional texts from this period (and beyond) can have characters, suspense, language and art that is beautiful in its own right, and a sense of fantasy or imagination that belies the practical purpose.

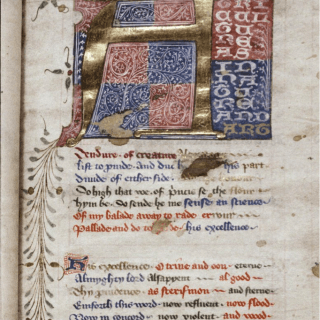

Part of this stems from each medieval book being unique, even if it contained the same text (or texts) as others. In a 15th-century agricultural manual, its owner — Humphrey of Gloucester, the brother of King Henry V of England — requested translation from Latin into his own language, as well as into poetry. In addition, the scribe used four colors of ink, rather than the standard one or two, to highlight the rhymes of the English poetry.

“This seems to be the translator saying, ‘Look: The poetry I can write is as technically interesting as the agricultural instruction in this book,’” says Cooper.

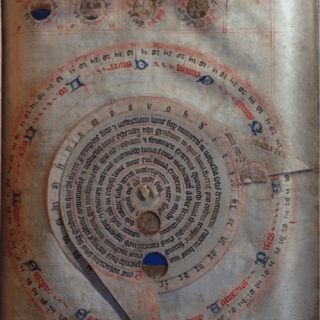

In another example, Chaucer created his Treatise on the Astrolabe for his 10-year-old son, Lewis. An astrolabe, originally introduced by Islamic scientists, allows users to map their position on earth, tell time and predict the movement of heavenly bodies.

Chaucer explains in his prologue to Lewis that he has written the book in simple English because he knows that Lewis only knows a little bit of Latin. Even in English, Chaucer uses familiar and even personal terms that might seem out of place in great classical works:

The zenith [center point]…is imagined to be the point straight above the crown of your head….From the zenith come arched lines like the legs of a spider, or else like the ribs of a woman’s hairnet….

As scientific research became more professionalized – primarily around the late 18th and early 19th century – the gulf between hard science and the arts grew wider. Though medieval universities promoted degrees in the liberal arts, the modern university system began to divide disciplines and encourage specialization.

Still, the phenomenon hasn’t disappeared completely. In December, The New York Times presented an “op-art” piece entitled “First, Catch Your Jellyfish” with examples from current cookbook instructions not necessarily intended for the average home cook. A recipe for “Gold, Frankincense & Myrrh” from Heston Blumenthal’s Fat Duck Cookbook asks for 50 grams gold frankincense tears and 100 grams water for the frankincense hydrosol (distilled plant material similar to an essential oil).

Travel guidebooks and popular nonfiction works by authors such as Michael Pollan (writer of the inaugural Go Big Read book In Defense of Food) also blur the line between aesthetic and instructional to lure readers in.

And then there’s the smartphone: practical, highly functional, entertaining and aesthetic in its own right.

“’There’s an app for that’ – even an astrolabe, if you want one!” says Cooper. “We’ve never really let go of the dulce et utile principle, and it seems to me we are demanding it more and more.”

Then, as now, combining beauty and utility reveals the most when it is most personal.

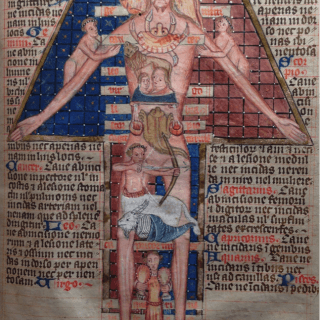

Cooper cites a “commonplace book” containing 21 separate texts, including a calendar, astronomical texts, an agricultural manual, details on purchasing spices and planting vineyards, a list of foreign exchange rates, and more.

“I love the idea of the moment when Robert Robynson decided to take this most organizing of practical texts, the calendar, and make it about himself and the life he lived: listing when he came to London as an apprentice, when he got married, and so forth,” says Cooper.

“On the last page of the book, he wrote that on the 19th of September 1532, ‘I shall be…if God send me life, the full age of 78 years.’ I find that very moving.”