Bold UW grad helped open college, workplace to women

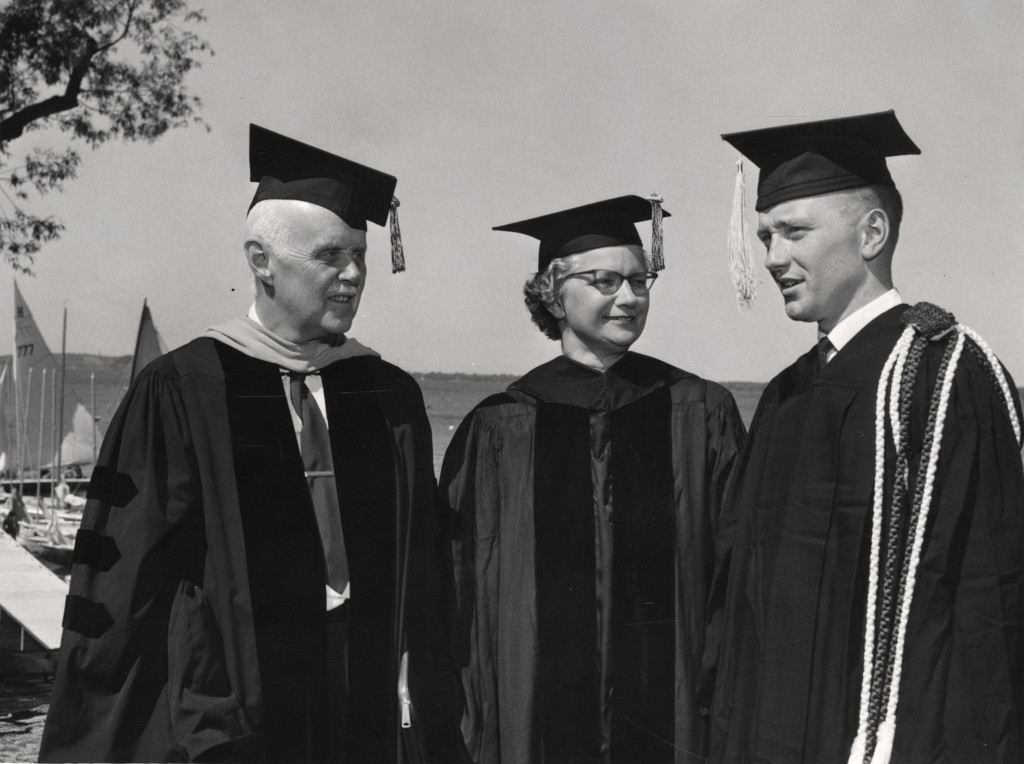

At Honors Convocation 1961, graduate David Sheridan from Milwaukee stands with UW Dean Mark Ingraham and Radcliffe College President Mary Bunting on Memorial Union Terrace. Photo courtesy of UW Archives

There’s a black-and-white picture on the first floor of Ingraham Hall that hundreds pass by daily.

Clad in caps and gowns are Mark Ingraham, professor of mathematics and former dean of Letters and Science, graduate David Sheridan from Milwaukee and Mary Ingraham Bunting-Smith, all attending the 1961 Honors Convocation at Memorial Union.

The building was named for Mark Ingraham, and Mary was his niece.

Mary Ingraham Bunting-Smith, a UW grad with degrees in agricultural bacteriology, had returned to her alma mater, this time not as a student but as president of Radcliffe College, a women’s liberal arts college in Cambridge, Mass.

At a June 3, 1961, dinner, more than 400 alumni gathered at Great Hall in Memorial Union to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Wisconsin Alumni Association.

Discussion turned to how UW–Madison wasn’t nearly as known as it should be.

“With a mischievous twinkle in her eye, she told the alumni, ‘If you really want to get Wisconsin in the news, elect a woman president,’” referring to the top position now known as chancellor, reported the Wisconsin Alumnus.

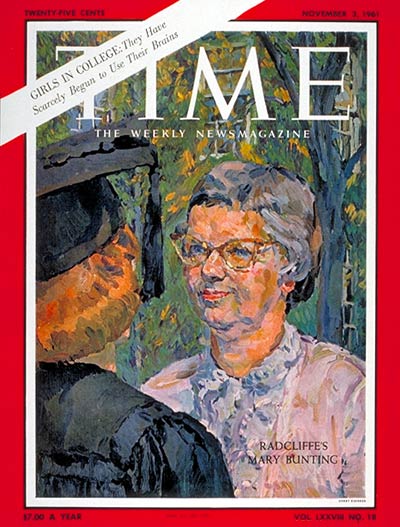

The UW aluma had the kind of forward thinking that landed her on the Nov. 3, 1961, cover of Time magazine.

The UW aluma had the kind of forward thinking that landed her on the Nov. 3, 1961, cover of Time magazine.

“GIRLS IN COLLEGE: They Have Scarcely Begun to Use Their Brains” announced Time, with a portrait of 51-year-old Ingraham Bunting-Smith painted by Henry Koerner; she was one of just four women to land on Time’s cover that year.

“Adults ask little boys what they want to do when they grow up. They ask little girls where they got that pretty dress,” she told Time. “We don’t care what women do with their education. Why, we don’t even care if they learn to be good mothers.”

Ingraham Bunting-Smith worked to change that. In honor of Women’s History Month, we celebrate her and all the other women who made history, even if buildings aren’t named for them. Yet.

In 1961, Ingraham Bunting-Smith was one of five recipients of an honorary degree from UW–Madison, one of the highest awards given by the university.

Mary was an indifferent student until she opened a chemistry book on a trolley ride and “fell in love” with bacteriology.

At UW, ‘everyone cared tremendously’

After graduating from Vassar in 1931, Ingraham Bunting-Smith headed to UW–Madison, a perfect place to learn all about “those little bacteria.”

“The students basically educated each other,” she told Time. “Everyone cared tremendously about finding out what was really true. It was by defending everything and fighting it out in the lab that you learned.”

She earned both her master’s (1932) and doctoral degrees (1934) from UW–Madison in agricultural bacteriology. Along the way, she met a tall, lean, kindly medical student “with a sort of quiet power” named Henry Bunting, the son of a pathology professor in whose class they met. After two years of hiking and bird watching, “we just knew we were going to be married,” she told Time.

He ended up getting a fellowship at Yale Medical School, and she worked in a lab for $600 a year. She pioneered work on microbial genetics, and found her research specialty — a bright red bacterium called serratia marcescens.

They bought 50 acres on a Vermont mountaintop and built a tar-paper shack retreat there. In 1940, the first of their four children (a daughter, three sons) was born.

While putting academia on hold to raise her young children, Ingraham Bunting-Smith managed to find time to run the 4-H club and served on the school board, sparking the building of a regional high school.

“When I was home all day, I got tired,” she told Time. “When I was working part-time, I could enjoy the ironing.”

Sadly, Henry became sick and stopped teaching one semester. On Good Friday in 1954, he died of brain cancer.

Ingraham Bunting-Smith was a widow at 43 with four children depending on her. She needed to work. And she knew other women needed to as well — or at least to have the option.

According to the 1961 Time article: “Of the top-ranked high school seniors who skip college, two-thirds are girls. The proportion of girls in college has slipped from 47% in 1920 (a vintage feminist year) to 37% now. Only a little more than half of all college girls get a bachelor’s degree.”

Ingraham Bunting-Smith didn’t have to choose between having a career or being a wife and mother. She didn’t think other women should have to choose either.

She had taught and conducted research at Bennington College, Goucher College, Yale University and Wellesley College. She met plenty of young women in college who were the first of their families to go to college yet had no idea why they were there.

“I didn’t think these girls realized how able they were, and how much they had to contribute,” she said.

In 1955 she became dean of Douglass College, and in 1960, she was named president of Radcliffe College, the undergraduate college for women at Harvard University.

Radcliffe students already took classes with Harvard students, but they were admitted to college separately and had their own living quarters, administration and trustees. Ingraham Bunting-Smith thought the system inequitable and worked to integrate the campuses more fully.

Fighting a ‘climate of unexpectation’

She quickly gained national attention for identifying a societal problem she called a “climate of unexpectation” for girls, which resulted in “the waste of highly talented educated womanpower.”

There’s nothing wrong with motherhood, Ingraham Bunting-Smith said, but many women want to do work outside the home as well.

And for that, women were going to need new role models.

“She won’t model herself on anyone who has rejected good family life or who has rejected an intellectual life to be a housewife in suburbia. What she needs to see is the person who has managed both.” Time magazine wrote. “The girl must find marriage, but she must also find what Mary Bunting calls ‘the thing that’s most important — having something awfully interesting that you want to work on awfully hard.’ ”

At Radcliffe, kept an open door for her students, and when they’d drop by she’d sometimes kick off her shoes and invite them do the same, and to join her on the floor. She encouraged students to drop by her house if her porch light was on, and they did.

“By example and precept, Mary Bunting has already gone far to counter the pressures against thinking women,” Time wrote.

Story sparked strong reactions

The story had people talking — and Time received a lot of letters in response.

“Just when I was beginning to feel that I was peculiar because I want to do something with my life besides bear children, along comes an article about a woman who has lived the fullest life imaginable that proves to me, and I hope to a lot of other girls in college, that all this is not in vain,” wrote Mary Margaret Buksas, a student at Creighton University.

Of course, not all agreed. “It seems to me that Mary I. Bunting is a perfect example of a woman who has been let out of the house too much,” wrote Robert L. Pyles of Harvard Medical School.

But it had only been a little more than 40 years since women got the right to vote. Things were changing, and with change comes resistance.

Ingraham Bunting-Smith kept at it.

She helped establish the Radcliffe Institute for Independent Study, with the help of $150,000 from the Carnegie Foundation and other grants. Its purpose was to pursue research into the psychological and cultural factors that affected women’s status in society, and also to support female artists, scientists and scholars, particularly those who had suspended their careers because of family responsibilities.

“During her tenure (1960-1972), Radcliffe students first received Harvard degrees, women were admitted to the graduate and business schools, and the Radcliffe Graduate School merged with Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences,” the Harvard University Gazette noted in her obituary.

After a phone call from President Lyndon B. Johnson, she took leave to serve on the United States Atomic Energy Commission (1964-1965), becoming the first woman to do so. (Listen to the call here.)

She retired from Radcliffe in 1972. She went on to help fully integrate women into Princeton University, signing on as special assistant for coeducation just three years after the university admitted its first female undergraduates in 1969.

In 1975, she married Clement A. Smith, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School; he died in 1988. Mary died Jan. 21, 1998, at the age of 87.

Women in college no longer a novelty

Partly because of Ingraham Bunting-Smith and people like her, women in college are no longer a novelty.

In fact, American women passed men in gaining advanced college degrees as well as bachelor’s degrees, according to the 2010 census. It was yet another milestone for women, one that followed women outnumbering men in college enrollment starting in the 1980s.

According to fall 2022 enrollment numbers for UW–Madison, 26,466 women were enrolled compared to 23,440 men. More women receive degrees, as well.

There is still a way to go: Women make up only one-third of all scientific researchers in the world, according to a February 2024 United Nations report. Only 28 percent of engineering graduates are women.

But thanks to people like Mary Ingraham Bunting-Smith, it isn’t quite as far.

She has a long list of accomplishments and accolades, but perhaps her greatest legacy is a question that little girls hear these days, as well as little boys: What do you want to be when you grow up?

A call from LBJ

Exactly 60 years ago today, Mary Bunting got a phone call.

“Is this Mary Bunting? This is Lyndon Johnson, Miss Bunting,” he said in his thick Texan drawl. “I have a little problem I want to see if you can help with,” he said. “I need a woman named Mary Bunting to sit on the Atomic Energy Commission.”

Johnson shared his frustration with not enough women being in public service. Johnson had been under pressure from women’s groups.

“I think that you could give the woman of this country not only a thrill, but you could show them by example and I would be naming women judges and women bankers and women everything else as soon as I got you confirmed,” Johnson said.

Mary, always practical, wanted to know when the position would start.

“Yesterday,” Johnson says without skipping a beat.

She said she’d need to talk to some people about

“They’ll all talk you out of it,” he said. “What I want to do is get a top-flight woman into a top-flight job.”

Mary had questions about what was expected and if she was sufficiently qualified.

President Johnson assured Mary that Chairman Glenn Seaborg was aware of her impressive background.

“He’s got everything in the world on you, honey,” Johnson said. “He’s a wonderful man. He’s almost too wonderful. I just wish he’d say ‘dammit’ once in a while.”

“Maybe I can do that for him,” Mary laughed.

“You can do that for him — I’ll have the White House operator put you in touch with him. You think it over tomorrow and then give me a ring. Just call me collect at the White House.”

Listen to the call here.

On June 29, 1964, Mary was sworn in by Johnson.

“Congratulations are due the new commissioner, but really the country can congratulate itself on the good fortune of Mrs. Bunting’s example of good citizenship in taking this very important office,” Johnson said.

“I believe we can say objectively that no woman has shared in a responsibility to all of humankind so great or so grave as Mrs. Bunting is assuming today.”