Book Smart

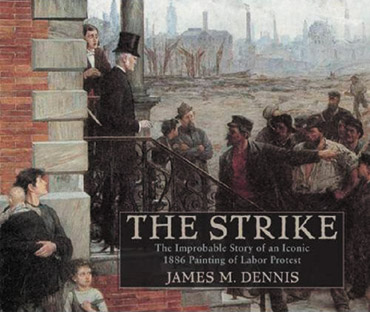

Professor emeritus of art history Jim Dennis recognizes the crack timing of his new book, “Robert Koehler’s The Strike: The Improbable Story of an Iconic 1886 Painting of Labor Protest.” It mirrors the timing of his subject: an 1886 painting by Wisconsin painter Robert Koehler that has managed, repeatedly, to pop up when history finds it most inconvenient.

“It’s a biography of the painting, not of the painter,” says Dennis. “The painter’s life is background. The painting became so major.”

But the background, too, has a story that winds its way around many Wisconsin people and events. As labor and labor history once again take center stage in Wisconsin, the events that led to Dennis’ book reaffirm the connections between art and life.

The son of a master machinist, Koehler grew up steeped in Milwaukee’s German industrial heritage. His family arrived from Hamburg in 1854, early immigrants who found work supporting major metal foundries and manufacturers.

Returning to Germany for further study at Munich’s Royal Academy of Art, Koehler sought permission for a controversial subject in his diploma painting: a nine-foot depiction of industrial painters walking off their job and confronting management.

Robert Koehler’s The Strike: The Improbable Story of an Iconic 1886 Painting of Labor Protest (UW Press, April 2011). James M. Dennis, professor emeritus of art history

Though Koehler said he was inspired by the great railroad strike of 1877, he did not intend it to depict a particular event. Painted in Munich, from models posed like the factory workers Koehler had visited in England, the painting nevertheless gained the mistaken reputation of being an American painting.

“It takes on an international quality in its development,” says Dennis. “When he went back to Germany, for some reason or other, German publications identified it as Belgian coal miner strikes. It was associated with Emile Zola’s novel ‘Germinal’ about strikers in northern France. So it was mistakenly identified, repeatedly.”

As the first major work to sympathetically depict workers walking off their jobs, the painting would have been a sensation on its own merits. It was reviewed and reproduced in publications including the New York Times and Harper’s Weekly.

But both the painting and the events surrounding its debut represented a widening gap between industrial businesspeople and members of the working class. Its first exhibition, on May 1, 1886, in New York, coincided with a massive strike for the introduction of the eight-hour workday. Three days later, Chicago would erupt in the Haymarket massacre, generally seen as the spark in the international labor rights movement.

Many prospective art patrons had earned their money from the type of work implied by the top-hatted owner in the painting, standing on the front steps of his genteel home as mill chimneys churn out smoke in the distance. Excitement at owning the painting paled when industrialist buyers saw the unrest depicted in such compassionate detail — the old victimized worker, the mother with her hungry children.

As Milwaukee’s own industrial exposition came on the horizon in 1889, industrialist E.J. Becker contacted Koehler for permission to display the painting. Eager for the painting to sell, particularly in his hometown, Koehler readily agreed. But on May 6, the primarily Polish workers of the North Chicago Rolling Mill went on strike in Milwaukee’s Bay View neighborhood. Gov. Jeremiah Rusk ordered an attack by the National Guard.

“Here comes the catch: as soon as Milwaukee industrialists and brewers saw the painting, they weren’t too pleased with it,” says Dennis, with a laugh. “Frederic Layton, who had just opened his gallery — The museum of the time — didn’t want to exhibit it because of the subject matter.”

On no less than three occasions, the painting faced obscurity specifically because of its purchase by wealthy patrons. In one such case, lumber baron T. B. Walker — titular head of Minneapolis art patronage, and the founder of what is today the Walker Art Center — headed a consortium that purchased the painting and hid it away in a dark corridor of the public library — a place visited by few working people at the time.

“It scared the pajamas out of the industrialists in Minnesota,” says Dennis. “They’d established something called Citizens Alliance — industrialists, the business community and so on — to counter the union movement. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?”

The painting’s universal appeal added to the perceived power of its message, dooming it to storage again and again. But the activist history of UW–Madison brought it back into prominence thanks to Lee Baxendall.

Born into a wealthy Oshkosh family, Baxendall’s exposure to Madison’s radical politics and protests in the 1960s led him to an activist life in Greenwich Village. While Baxendall and Dennis had crossed paths as students in Madison, they researched the painting independently.

Now a professor of art history, Dennis had received inquiries over the years from people interested in Koehler’s painting, many of whom had confused it with a similarly named painting owned by the then-Elvehjem Museum of Art. Though he, like others, believed that the painting was at the Milwaukee Public Library, he finally called and learned of his mistake.

Thanks in part to this clarification, Baxendall finally located the painting in Minneapolis, where it had lain in storage for nearly 60 years. He purchased the painting and had it restored. In the heady liberation movements of the 1970s and 1980s, the painting received more publicity than ever — including yet another abortive purchase by an industrialist.

In 1989, the painting found its current home at the Deutsches Historiches Museum in Berlin. Again, history surrounded the sale: the paperwork was finalized while the Berlin Wall fell just a few miles away.

And, again, Dennis found himself drawn to the painting.

With a background in both history and studio art, his own schooling had culminated with a dissertation on an Austrian sculptor who had done much of the work for the Wisconsin Capitol. After many years of specializing in American regionalists such as Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton — known for their populist art of the Great Depression era, in a similar climate of workers’ dissent — Dennis decided to return to his German roots.

As he restored a 16th-century German house from 2002-09, Dennis researched Koehler’s background in bits and pieces. When Baxendall, still enamored with the work after its sale, realized that he could no longer pursue the research in the manner it deserved, he sent his own efforts on to Dennis.

“I went to look at the painting in Berlin,” says Dennis. “It was in storage in Spandau after the wall went down. I made arrangements, and I became more and more interested in it.”

Dennis’ research is all the more remarkable because of the limited documentation with which he had to work. Koehler’s son had disposed of the family papers — including correspondence and notes — so Dennis often had to rely on published statements.

Still, the painting and its painter remain only part of the rich swirl of history that the book describes. With connections here in Madison and around the globe, the painting touched many larger-than-life characters: familiar names, notorious pasts.

The book is a fitting tribute to Dennis’ long career. Its vibrant sense of place and culture reminds readers that art is so much more than pigment, line or shape.

“I’ve always stressed the social history of art when I went about teaching my survey courses,” says Dennis. “It’s really a social history of the painting and its reception — either acceptance or rejection. The class conflict involved is still with us today.”