Seed by Seed

Artists bring Ho-Chunk beadwork to Bascom Hall on a grand scale

The first few times they met, Molli Pauliot and Marianne Fairbanks simply talked.

The two — Pauliot is a UW–Madison PhD student, Fairbanks a faculty member — had been commissioned to create banners for the university’s 175th anniversary. But before designing anything, they spent time getting to know each other. They bonded over their mutual love of basketry, textiles and beadwork, and Pauliot, who is Ho-Chunk, shared the meaning behind some of the traditional Ho-Chunk images and symbols.

“I don’t think we could have skipped over all those initial meetings,” says Fairbanks, a textile artist and an associate professor of design studies in the School of Human Ecology. “It helped us become comfortable with each other.”

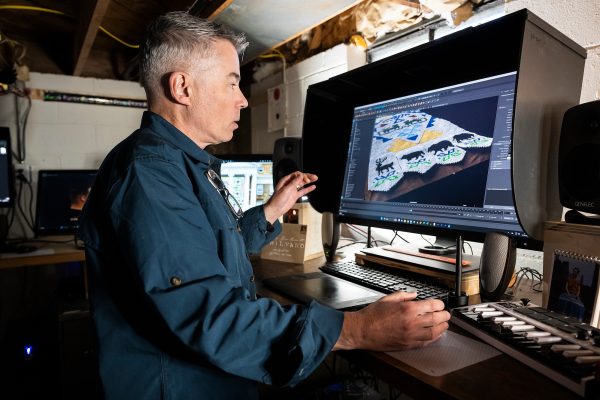

After completing their design work, Pauliot and Fairbanks sent the two-dimensional graphics to Stephen Hilyard, a professor of digital arts in the Art Department, who used 3D animation software to create the effect of 160,000 individual small beads called “seed beads.”

The title of the piece is “Seed by Seed.”

Pauliot, who began sewing and quilting at age 9, says the banners include nods to Ho-Chunk history and culture that may not be obvious to the non-Ho-Chunk.

“I felt a lot of community pressure when I started working on this project,” says Pauliot, whose dissertation topic is an ethnographic history of the traditional Ho-Chunk black ash basket. “I thought, ‘This needs to be good. This needs to be something the Ho-Chunk will be proud of.’ When I tell Ho-Chunk alumni about the project, there’s been a lot of excitement. They think it’s so cool and are really happy about it.”

Connecting past to present and our shared future

The fruits of the creative partnership formed by Pauliot, Fairbanks and Hilyard can now be seen at one of the most prominent sites on campus. The banners they designed — three panels, each about 7 feet by 16 feet — hang from the front of Bascom Hall, the university’s central administration building. The design incorporates symbols, imagery and traditional colors of the Ho-Chunk Nation, honoring those whose ancestral land UW–Madison now occupies.

“Molli, Marianne, and Stephen — I am so honored to recognize your wonderful collaboration that has given us this amazing work of art. Thank you!” Chancellor Jennifer L. Mnookin said on Nov. 7 during a ceremony on Bascom Hill celebrating the banners. “The title of this piece —‘Seed by Seed’ — reminds us of the work we are doing to acknowledge that this university sits on the ancestral homeland of the Ho-Chunk people, who were forcibly removed from this place. And it reminds us of our ongoing responsibilities to move our campus community from ignorance to awareness, and that this work can’t be confined to a day, a month or even a year. It’s a work of a lifetime.”

The installation of the banners this month coincides with Native November, an annual campus celebration of Indigenous culture. The banners will remain up through November, then return during the spring semester as part of a regular rotation of themed banners.

“When the university first raised the flag of the Ho-Chunk Nation two years ago, it made national news,” says Pauliot, who is pursuing a doctorate in cultural anthropology. “It also started a lot of discussions about the university and its relationships with Native Nations. That’s what I’m hoping happens with these banners — that they continue this conversation and expand on it.”

“Textile language is all about abstraction,” Fairbanks says. “So even something that looks abstract, like the four squares in the banner design, can be a reference to the four lakes in Madison. I often talk to my students about this — just because something is abstract doesn’t mean it is devoid of meaning. We’re not trained very well as visual thinkers to analyze what we are seeing, but I think once we spend a little time and dedicate ourselves to thinking more about what something could mean, then we uncover deeper meaning and narratives.”

Throughout the design process, Pauliot and Fairbanks drew inspiration from beaded bandolier bags — dazzling objects that showcased remarkable technical skill and were highly valued when trading with other tribes. Using the latest 3D software, Hilyard sought to replicate some of that intricacy on a grand scale.

“I was very happy to be involved,” he says. “I felt it was such an important thing to see Ho-Chunk beadwork in one of the most marquee sites on campus. This seems like an important thing for the university to do.”

Pauliot finds the beads an apt metaphor for the developing relationship between UW–Madison and the Ho-Chunk Nation. She serves as the project assistant for Our Shared Future, a university initiative that represents UW–Madison’s commitment to respect the inherent sovereignty of the Ho-Chunk Nation.

“In beadwork, you weave together, one by one, thousands of seed beads to form something beautiful,” she says. “That’s how I view Our Shared Future. With each little positive interaction, we are hopefully weaving together, seed by seed, a future based on collaboration and mutual respect.”