The Black Student Strike of 1969

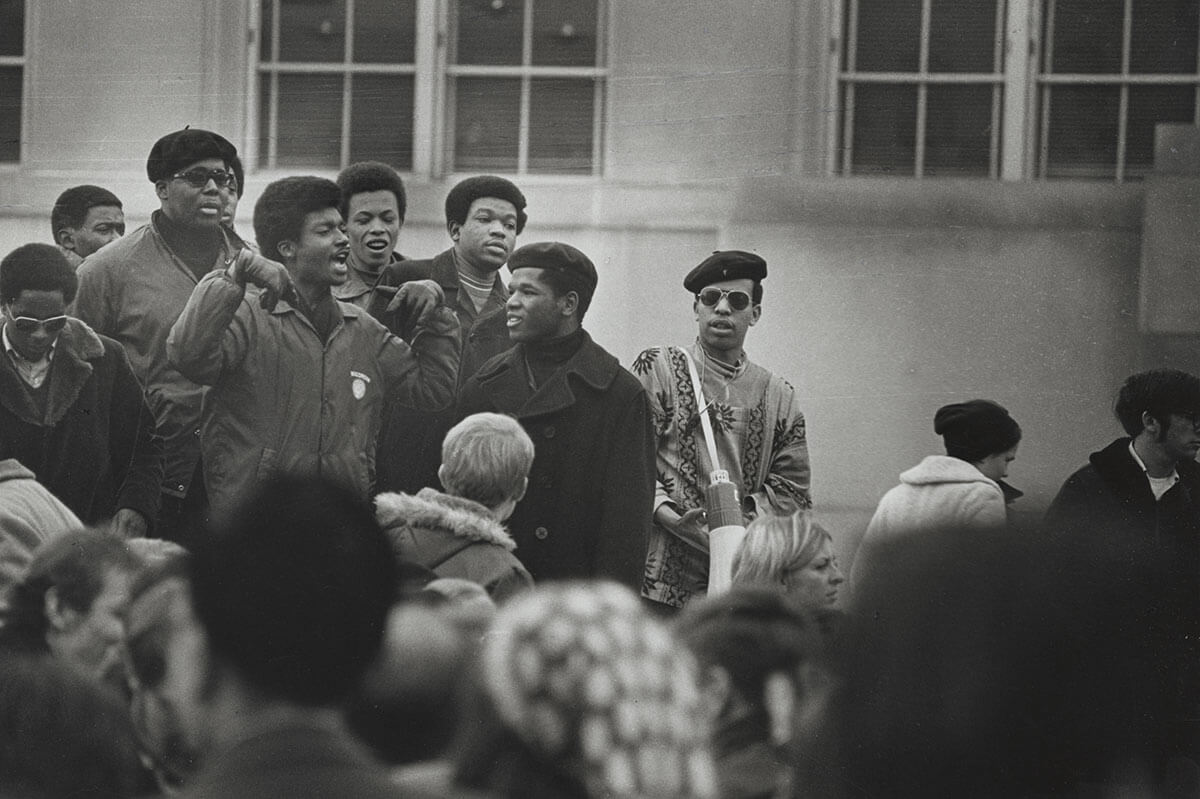

Fifty years ago, black students at UW–Madison, propelled by longstanding grievances and fresh flash points, called for a campus-wide student strike until administrators agreed to 13 demands. Joined by thousands of white allies, they held rallies to educate the community about racial inequities, boycotted classes, marched to the state Capitol, took over lecture halls and blocked building entrances. The latter actions spurred the governor to activate the Wisconsin National Guard. The protest, surging and ebbing over roughly two weeks in February 1969, was among the largest in the university’s history. Dubbed the Black Student Strike, it would forever alter the campus. Here, in their own words, participants recount why the strike was needed, what they did, and how it changed the university and their lives.

Timeline

Story

The Black Student Strike played out amid a burgeoning Black Power Movement and in the raw aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination the previous spring. Massive protests over racism and the Vietnam War roiled campuses across the country, including UW–Madison, where a demonstration against Dow Chemical in October 1967 marked the first use of tear gas on campus.

Starting in 1966, black students began organizing by educating themselves, bringing in speakers and advocating for changes with the university administration. By February 1969, black students were frustrated over what they considered meager progress on race-related campus goals, and they were outraged that 94 black students at the University of Wisconsin campus in Oshkosh recently had been expelled following a protest there. A week-long conference at UW–Madison on "The Black Revolution: To What Ends?" further emboldened students.

Liberty Rashad Leader of the campus Black People’s Alliance and a strike organizer

We had a lot of issues we wanted to deal with. The fact that there was an African Studies Department but nothing about "African America," so to speak, was quite distressful. So we immediately targeted that as a big issue we wanted to tackle. And secondly, we wanted to increase the number of African-American students — students of color in general — on campus, because it was just outrageous that you have this huge university with this teensy-weensy minority that’s not even a drop in the bucket.

Donna M. Jones Strike organizer and spokeswoman

The university kept saying it had almost 1,000 black students, but no one believed that. We determined that many of those students were from Africa. There were not nearly as many African-American students. So we definitely wanted more black students and more black faculty members. (The university did not publicly report enrollment data by race at the time, only by country of origin.)

Hazel Symonette Graduate student and strike participant

What I remember as a triggering factor was the Five Year Program. The director was a white woman. The person was nice and had done good work to even get the program started, but it needed something different. So there was a lot of turbulence around that. (The program was an early effort to recruit African-American students.)

John Felder Strike organizer and spokesman

We were also aware that, after Martin Luther King had died, we were part of a continuation of the Civil Rights Movement. We wanted to do our part in our location to advance the cause.

Gerald Lenoir Strike participant

Black students, including me, were going through what one sociologist dubbed "the Negro-to-Black transformation." We were cementing a new identity that was in formation when we arrived here, and we were fighting to be recognized as full human beings worthy of recognition in all of our dimensions.

Oral History Participants

Meet Harvey Clay First-year student, football player and a leading protester

Harvey Clay arrived at UW–Madison on a football scholarship in the fall of 1968 — a 6-foot-8-inch, 255-pound center. A native of Midland, Texas, he was a member of the last graduating class of a segregated high school. The transition to Madison was brutal – "There was no black food, there were no black clubs, there was no black community." He hoped life would be different here, but he found only more discrimination. "Racism isn’t regional," he says. "It exists all over."

I remember growing up seeing, in a little town called Garden City Texas, an older black woman probably 85 years old getting beat down by two policemen, back down to the floorboard of a car, when I was about 6 years old. I can’t forget that. So I was already damaged goods when I got there (Madison) from the ravages of the South and being exposed to it. I thought Wisconsin would give me a much fresher perspective without having to go through some of that. When I got there, I found out we were still going through the same thing in Madison that we were going through in Texas that I didn’t know would exist in the great North.

Meet Frank Emspak Member of the steering committee of The United Front, a group of white students who supported the strike

As a high school student in Yonkers, New York, Frank Emspak picketed a local Woolworth's, part of a nationwide effort to end the department store chain’s discriminatory service and hiring policies. It was the beginning of decades of activism for Emspak. At UW–Madison, while earning a bachelor’s degree in zoology, he became president of the UW Socialist Club and helped launch the national anti-Vietnam War movement as chairman of the newly formed National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam. By February 1969, he was a doctoral student in history and a teaching assistant in a black history course launched that semester. Of campus activism at the time, he says, "What we saw was a coming together of people who had moral and political objections to the war and to racism."

The effect on me as a student – I thought it was a very exhilarating thing. I think it certainly made our Black History class more interesting to people, more real to people. And it helped frame the discussions we were having.

Meet John Felder Strike organizer and spokesman

Days before classes even started in the fall of 1968, John Felder, a freshman from Brooklyn, New York, remembers being mesmerized by a group of black upperclassmen at an informal gathering at Memorial Union. "They were talking about some of the situations on campus, and I was immediately engaged by the language," he says. "It was much more free-flowing than I was used to." Felder had been recruited to UW–Madison as a participant in the Five Year Program, an early effort to increase the number of African-American students. Within a few months, at age 18, he was leading press conferences as a prominent spokesman for the Black Student Strike. "There’s a part of me that’s sort of shy, but I really asserted myself in that role." His college experience included flying to New York City to explain the demands of black students on "Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr.," a popular national public affairs show.

I thought, along with others, that this was a moment that had to be seized.

Meet Geraldine Hines First-year law student and strike participant

A native Southerner, Geraldine Hines earned her undergraduate degree at Tougaloo College, a historically black, liberal arts institution in Mississippi. Recruited by the UW Law School, she found herself one of only four black students in a class of 300 in the fall of 1968. "I had never lived outside of the Deep South, so going from a mostly black environment to a mostly white environment was quite traumatic." She believes she was the only law student who took part in the strike.

There was a small group of people that welcomed me and I felt welcomed by them but for the most part it was a lonely existence. But then again, I didn’t go there expecting to be accepted in that environment, you know? I went there to get what I needed and to get out.

Meet Liberty Rashad Leader of the campus Black People's Aliance and a strike organizer

As a high school senior, Liberty Rashad traveled from Harlem to Madison to visit her stepbrother, a freshman at UW–Madison. Things went well. "I enjoyed myself quite a bit – maybe too much," she says, laughing. She enrolled the following year and arrived in the fall of 1966. Immersing herself in the Black Student Movement, she helped found the Black Student Union on campus. Years of preparation led to her high-profile role in the Black Student Strike. Some of her fondest memories are of herself and her fellow black students educating themselves by bringing to campus prominent black intellectuals, activists and speakers, including Muhammad Ali, Toni Morrison and Stokely Carmichael. "It was a very special part of my education at UW," she says.

We just felt like it was our duty, we were there, to raise those issues, make it happen while we had that time. You know, we knew we were there and we’d have to use every minute that we could to do the work necessary to bring that about and that’s what we set out to do.

Meet Wahid Rashad Strike organizer and a leader of the campus Black People’s Alliance

Born in Arkansas with the given name Willie Edwards, he moved to Chicago with his family at a young age. In high school, he trained as a youth organizer through a program at the University of Chicago. He put those skills to use his first semester at UW–Madison, calling a meeting in the fall of 1966 that led to the creation of the Black Student Union. He became the group's first president. He fell in love with another founding member, Liberty "Libby" Davis, and the two married the following summer.

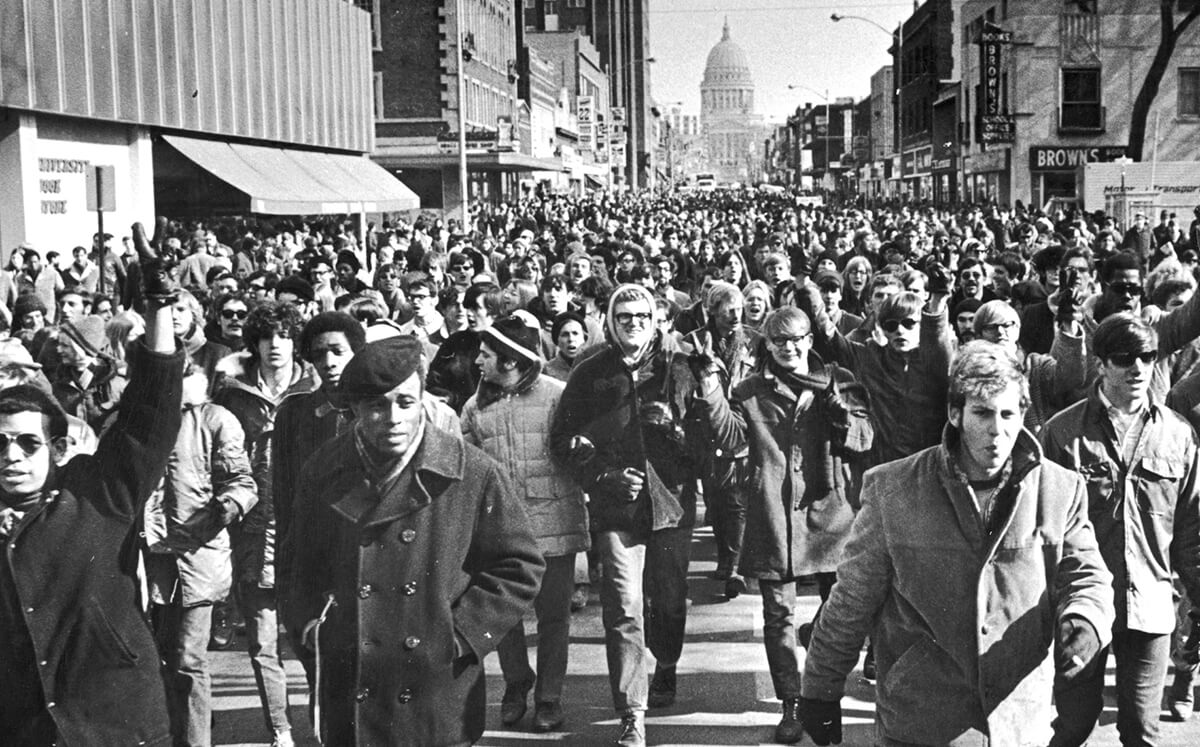

The main thing I was pleased with is the amount of support that we got from just the general population because there wasn’t many black students there, you know? And the fact that we got thousands of students and we were able to walk up State Street to the state Capitol. We shut down State Street. We came off the campus and walked up and there was like one side of the street to the other side of the street, just students, walking.

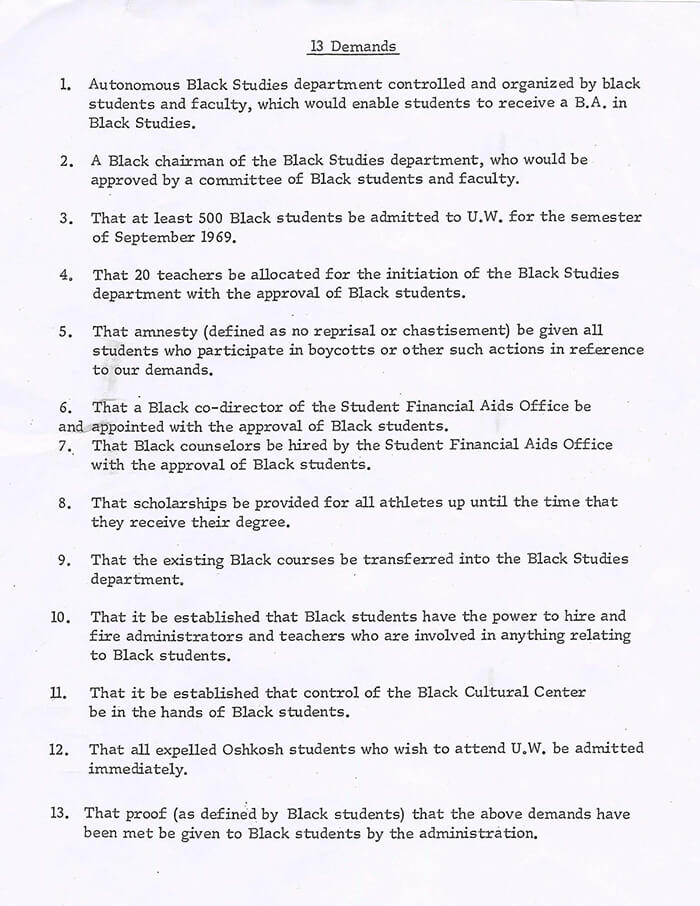

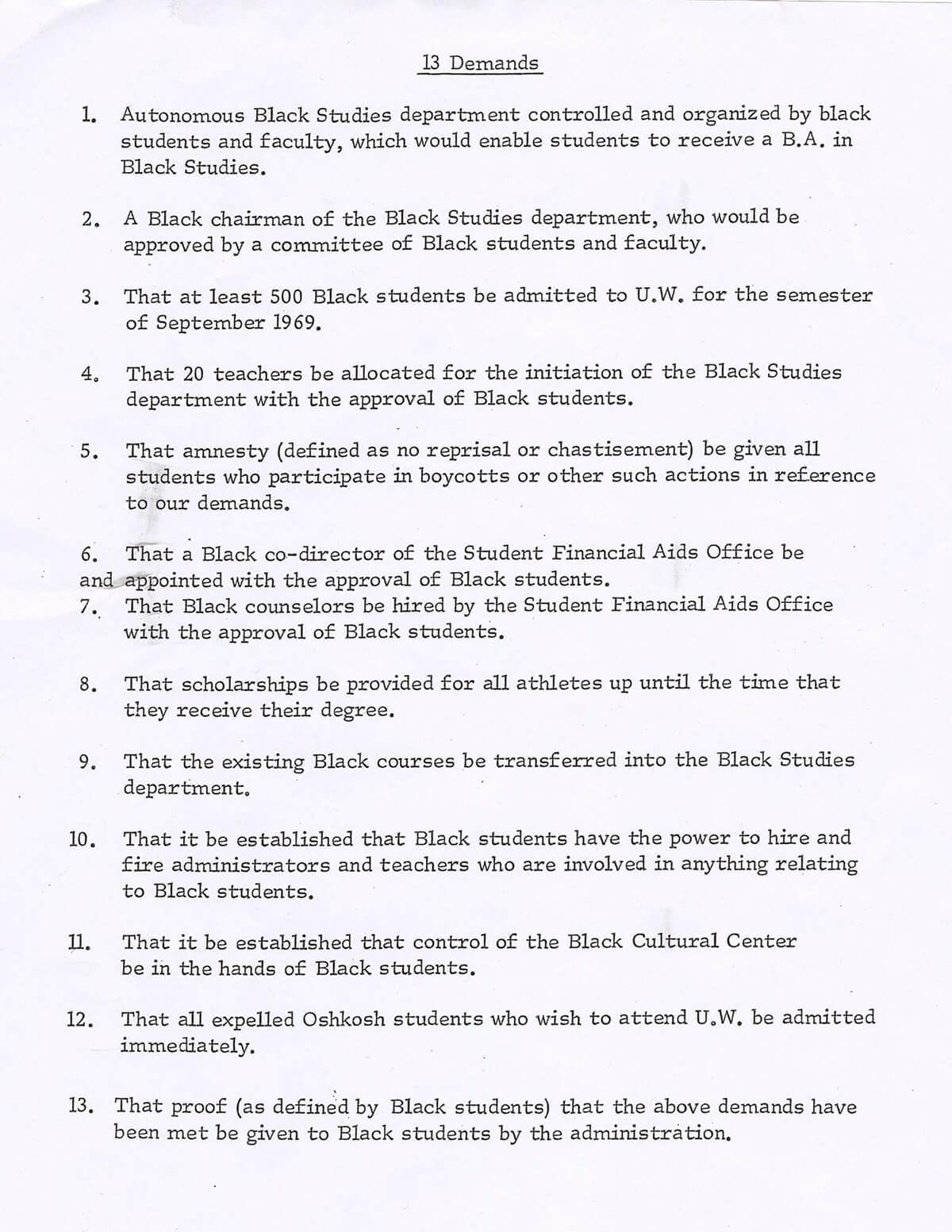

On Feb. 7, 1969, black students presented 13 "non-negotiable" demands to the administration, including the creation of a Black Studies Department, the admission of at least 500 black students for the fall semester of 1969, and the immediate enrollment of any expelled Oshkosh students who wanted to attend UW–Madison.

Liberty Rashad: (The administration) had been promising and they’d been reneging on their promises. There was just a whole lot of back and forth, back and forth, until we got to the point that we said, "OK, these are our demands now." And what we did to back up the demands is, "If you’re not going to meet them, we’re going to organize a strike."

John Felder: There was such resistance, such a refusal to do anything, that we thought that it was necessary for us to go on strike.

Liberty Rashad: We were pushing it to the limit to get what we wanted, and that was sort of our last resort.

In a four-page response, UW–Madison Chancellor Edwin Young said the university had been "challenged to do more to give black people adequate weapons with which to fight their way out of misery and poverty" and that "this is a kind of challenge we gladly accept." He contended progress was being made, pointing to courses in Afro-American studies, a seminar on black history offered the prior two semesters, and a black literature course established by the English Department. The student protesters deemed the measures inadequate.

It’s important to remember that the student strike was the culmination of three years of efforts – many meetings, agreements made and broken, a relentless faith in the protest process. It got to the point where we felt that the only power we had left was the power to disrupt. We held the university to the standard they committed to – equality – and told them basically, "Put up or shut up."

Wahid Rashad

Strike organizer and a leader of the campus

Wahid Rashad

Strike organizer and a leader of the campus

Black People’s Alliance

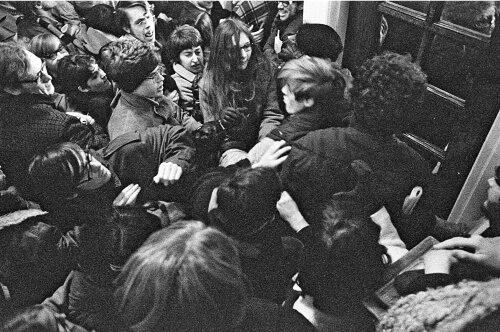

Strike leaders called for a boycott of classes starting Feb. 10, 1969. On the first day, as many as 3,000 students demonstrated in front of 10 campus buildings, emphasizing the boycott of classes and nonviolent confrontation.

Geraldine Hines, a first-year law student and strike participant: I can remember being at the Law School and sitting on the steps and making it known that I was part of it and that I was striking. One of the assistant deans came by and said to me that it was disgraceful and that I should not be doing that and that it was unbecoming.

They changed to more disruptive tactics the next day, blocking building entrances and bursting into lecture halls to halt classes.

Richard Spritz First-year student and strike participant

(UW–Madison Police Chief) Ralph Hanson would come out with a bullhorn, yelling, "Aaaah! Aaaah! Disperse! Don’t block the buildings!" And people would be yelling, "On strike! Shut it down!" And there would be police with riot gear on.

John Kaminski Student

Our political science class was occupied by 10 to 15 young black men who demanded that we stop the lecture and discuss "democracy" and the need for an African-American Studies Department. When Professor William Young put the issue to a vote, the entire class voted that he should continue lecturing, whereupon several of the black males literally picked Professor Young up and carried him out of the classroom.

Striking students presented administrators with 13 demands, including the immediate enrollment of any expelled Oshkosh students who wished to attend UW–Madison. Ninety-four students at Wisconsin State College Oshkosh were arrested and expelled following a November 1968 protest that came to be known as Black Thursday. Photo by John Wolf

David Marcou Student

Our calculus professor was a tiny man physically, with a quick wit and generally winning style. But he didn't know what to do when Harvey Clay ascended the lecture stage and tossed a very large metal desk like kindling off the stage. I learned a lot from that incident. Black students did have legitimate grievances and needed to do something to gain positive attention and action.

Harvey Clay First-year student, football player and a leading protester

I grabbed the desk and tossed it in rage. I just thought at the time that we weren’t respected. I was completely ticked off and felt that at least we should be respected and be able to voice our opinion. I had been beaten by the police for no reason. Some people would say, "Why wouldn’t you remain calm?" Calm for what?

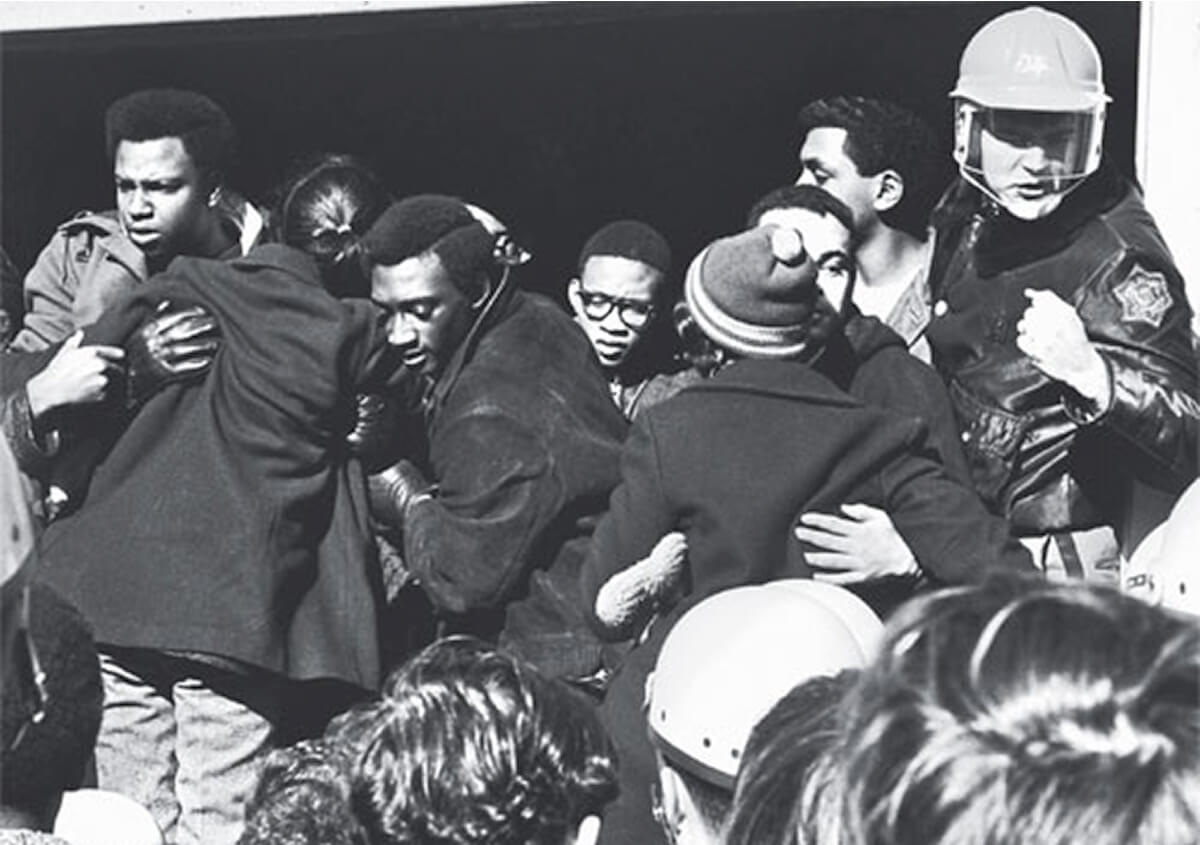

Clay was one of at least two dozen protesters, both black and white, arrested by campus and area police during the strike, sustaining a head wound in the process. Clay says he was trying to protect female protesters from being knocked over by rampaging male students who opposed the strike.

Harvey Clay: I was probably the biggest, most visible sight there, so I became a target. I was blindsided when one of about 13 or 14 police officers cracked my head open with a riot stick. I still have the scars.

Gerald Lenoir: I remember being bum-rushed by the Madison police as they came through swinging billy clubs. I remember them pushing me aside and brutally beating Harvey to the ground.

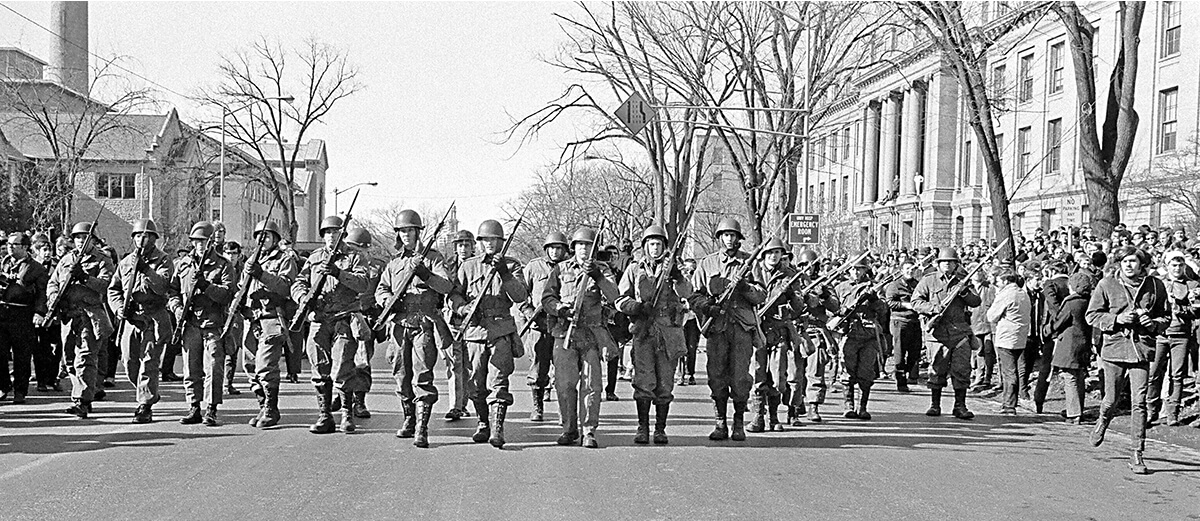

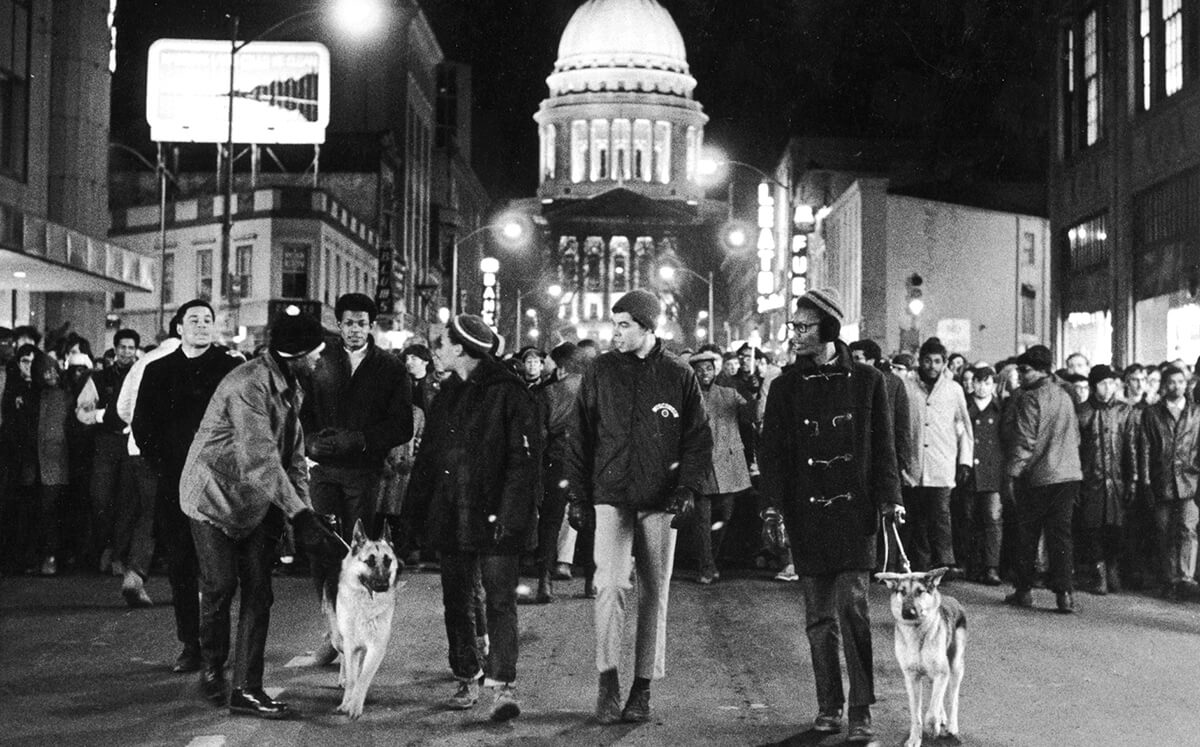

On Feb. 12, after the UW police chief said the disruptions were more than 350 police officers could handle, Gov. Warren Knowles activated 900 Wisconsin National Guard troops. Commenting to the press, he called the protesters "a radical element," adding, "the educational process must be able to move forward (and) the lives and safety of students and faculty and the property of the university must be protected." The guardsmen, many of them UW–Madison students, arrived the next morning.

Guardsmen with bayonets fixed to the muzzles of their rifles march down University Avenue. Photo by John Wolf

Frank Emspak Member of the steering committee of The United Front, a group of white students who supported the strike

Think about this: You have somebody who is a student yesterday, who may or may not be a racist, who doesn’t like what’s necessarily going on, standing there with a loaded rifle as you’re walking by.

Liberty Rashad

The adrenaline was very high. What we knew was that we had to run circles around them, and that’s what we did. That was our strategy, to keep moving. We had people here, there and everywhere, and we’d be over here creating a disturbance, and they were running trying to keep up with it. I remember they had helicopters circling all over town. We were nonviolent and we stuck to that, but they used tear gas, they used pepper spray, and they used their batons.

Photos by John Wolf

Minton Brooks Strike participant

Activating the National Guard was the last thing they should’ve done, because then it really became magnified tremendously, and huge numbers of people would come out.

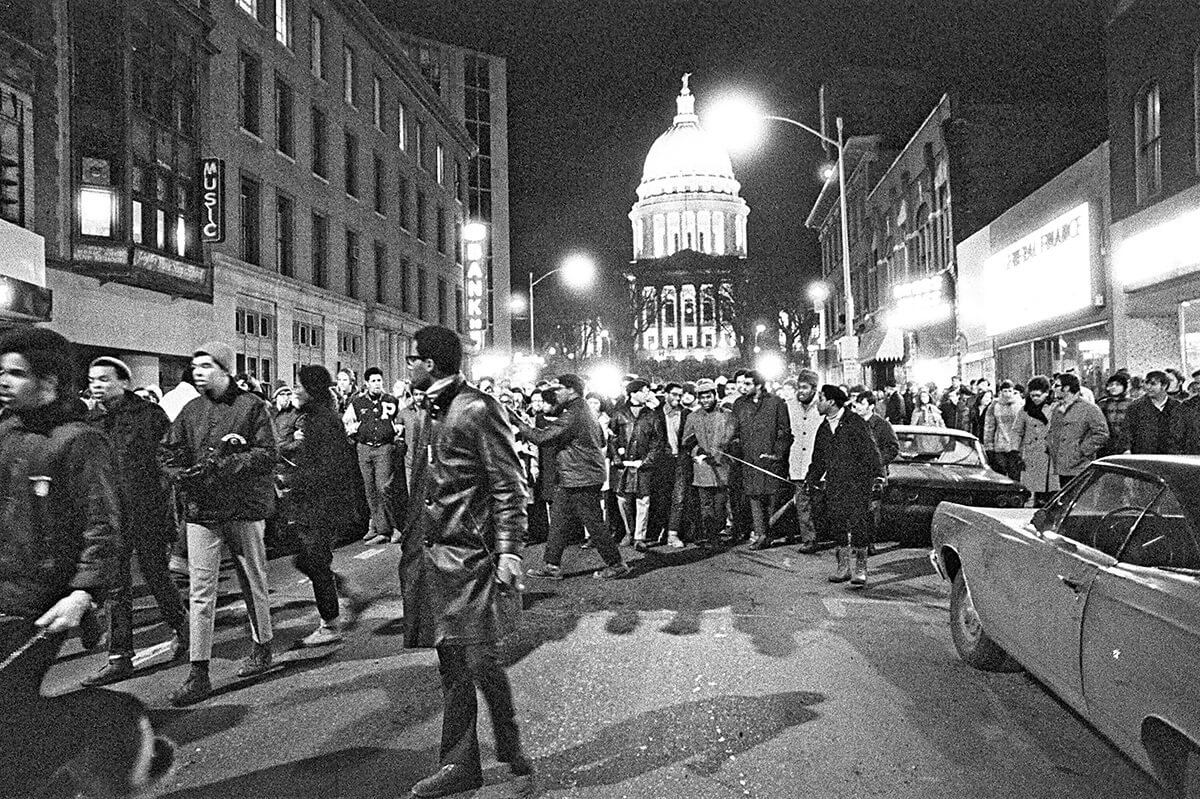

On the evening of Feb. 13, an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 people – the largest crowd of the strike – marched without incident to the Capitol.

Donna M. Jones: That was really a triumph. It was a turbulent time for the country, so if you had a nonviolent march, especially one of that size, it was considered a tremendous success.

Wahid Rashad: We shut down State Street. One side of the street to the other side was students walking. Seeing this crowd of people following you – it’s overwhelming and impressive.

Minton Brooks: It was an amazing phenomenon. How many times do you have a relatively small group of black people leading thousands and thousands of white people in the streets? It was incredible to have this sense of unity toward these explicit demands.

Indeed, white students, many of them learning about racism for the first time, had become important allies.

Minton Brooks

My perspective was that of a relatively clueless, white, upper-middle-class guy, of which there were many at UW. I went to Van Hise Hall and blocked the doors there and was confronted by really nasty objections from students just wanting to get to class. The strike had a big impact on me because it was the first time I put my body on the line, blocking doors and dealing with screaming students.

Richard Spritz

By complete chance, my assigned roommate as a freshman in Witte Hall was a black student from the far south side of Chicago. We became firm friends, as I did with his best friend, a high-school classmate. I think they felt completely marginalized. It was a university of mostly white people that was mostly speaking to white people and white people’s goals and aspirations.

Dolores Emspak Graduate student

(The racism) was not only prevalent but very out front. I can remember going around trying to raise money for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee for their drive for voter registration. People in the dorms who had probably never even spoken with a black person in their whole life would say to me, "We don’t think they should be allowed to vote." Nobody made any effort to even hide how they felt.

Kathy Schneider Michaelis Strike participant

On the night that thousands of us marched around the Capitol Square, my parents in small town Wisconsin actually picked me out of the crowd. I’m only 5 feet 2 inches, but I was recognizable by the huge brown-and-white scarf my mom had made me. Their reaction was not positive.

Donna M. Jones

The participation of white allies was very valuable. The anti-Vietnam War protests and the black student protests really supported each other, because at the time it was well known that poorer men were being drafted for the war and black men were disproportionately dying on the frontlines. So when they marched, we supported them. And when we marched, they supported us.

Maury Cotter White student who, together with a black student on her dorm floor, landed a meeting with the UW System president

We thought if the two of us went, we would represent the issue from multiple perspectives. We had no idea the university had a chancellor, so we went to the president of the System. We were naïve enough to be so bold to ask, and they likely thought we had more influence than we did.

Upon arrival, Cotter and her friend were greeted by the president. When it became apparent that they were not representing an official group, a vice president continued the conversation with them.

Maury Cotter

We tried to tell our perspective of what we thought was important. I don’t know if anything came of it beyond that, but we thought meeting face-to-face would help create better understanding. It’s a philosophy of mine: Do what you can from where you sit, and do it as authentically as you can with your own perspective and story and with whatever influence and power you have, no matter how limited it may be.

While thousands of students supported the strike, many did not. Some opposed the group’s demands; others supported the demands but not the group’s tactics. And some students simply didn’t appreciate their education being interrupted.

Frank Emspak

Basically, it was not business as usual, but you have 35,000 students on campus. Even if 5,000 or 6,000 people are doing something, most people are not, and that was also true.

Some students actively confronted the protesters, including posting a sign to the Abe Lincoln statue atop Bascom Hill reading, "Down With Student Fascism." Strikers and counterprotesters occasionally scuffled.

Wahid Rashad

We were on Bascom Hill and there were these white football players who wanted to disrupt us and push us around, but the black wrestlers and black football players came and pushed them back and backed us up.

UW–Madison administrators were far from alone in their opposition to the strike. A petition signed by 1,372 faculty members, about two-thirds of the faculty, supported the administration’s stance.

Frank Emspak

I wish we had been able to win the faculty vote. On the table were all the black demands, and the university’s position was, "We have to support the chancellor. We have to support the governor calling out the National Guard." A law-and-order position, basically.

For the leaders of the protest, the strike was both a major growth experience and a culmination of years of study and preparation.

Harvey Clay: I was very nervous. I’m a country boy from Texas. I had never participated in anything like that. I was trying to help make a difference and trying to get some fairness that I thought we did not have at the university.

Wahid Rashad: We were versed in the issues. You couldn’t out-talk us or intimidate us in a debate. If we got on TV, we articulated. We got the support of the community from that articulation and the self-education we gave each other. We were comfortable and confident.

Liberty Rashad

We just worked, worked, worked, worked, and we organized, organized, organized. It took a lot of that to make it happen.

Frank Emspak

I just remember endless meetings.

By Feb. 21, strike organizers had called for a moratorium on protests due to smaller turnouts, though there was a brief flare-up on Feb. 27.

Frank Emspak

It was a brilliant success for a week. The number of people probably peaked on the Tuesday and Wednesday of that second week, and then petered out.

Wahid Rashad

It was the winter. Less and less people came out. We never said, "It’s over." I wish it had gone on longer, but I understand that people have exams and stuff.

Liberty Rashad

It’s kind of a blur to me right now (how long the strike lasted). It was enough time for (the administration) to give in.

On March 3, the Faculty Senate, on the recommendation of the campus Committee on Studies and Instruction in Race Relations, OK’d a plan to create an Afro-American Studies Department. The committee had been researching the issue since May 1968. However, because of the protesters’ demands, the committee moved from a conversation about individual black history and literature classes to a recommendation for a full department.

Seymour Spilerman Assistant professor and a member of the Committee on Studies and Instruction in Race Relations

There was a feeling that the university had to take steps to show that it understood the pain of African-American students, while not necessarily agreeing with how they were expressing that pain. It certainly was the right thing to do, and perhaps it should have been done earlier.

Hazel Symonette

That was a major accomplishment to get that department.

The Afro-American Studies Department, which exists to this day, began in the fall of 1970 and is considered the most tangible result of the strike. Other outcomes were less direct, though many people credit the strike with a renewed commitment on the part of the administration to recruit African-American students, to hire and promote faculty and staff of color, and to strengthen the campus Afro-American & Race Relations Center by hiring a permanent, full-time director.

Frank Emspak

It would have been nice to say we had this great march down State Street in victory, but that’s not what happened. There were clearly changes made, though we didn’t get the additional 500 African-American freshmen, that’s for sure.

The earliest reporting of student race/ethnicity in official university records came five years later, in the 1974-75 academic year: Of 36,915 undergraduate and graduate students, 825 (2 percent) identified as African-American. In recent years, the data collection has changed to allow students to report multiple racial identities. In 2018-19, of 44,411 students, 1,443 (3 percent) identified as African-American, either solely or in addition to other identities.

Liberty Rashad

There wasn’t any way for us, as students who were leaving or graduating, to see those kinds of things through, which is always the problem with campus movements. (Other students) have to keep on pushing, keep on making a loud noise and keep on doing stuff that would push the envelope further.

Wahid Rashad

I don’t have any regrets. I think the strike was a success. I was very pleased that we got our issues out there in the whole community, and we did it in such a way that there was a lot of support. The university began talking about spending more money (on the issues we’d raised).

Hazel Symonette

We stand on the shoulders of those undergraduate activists who sacrificed and gave so much — some of whom lost the opportunity to secure a UW degree.

Wahid Rashad

If I came back to campus, I would say this to black students: "Do not feel marginalized. Be you. Be confident and do your thing. Let your light shine."

Where Are They Now

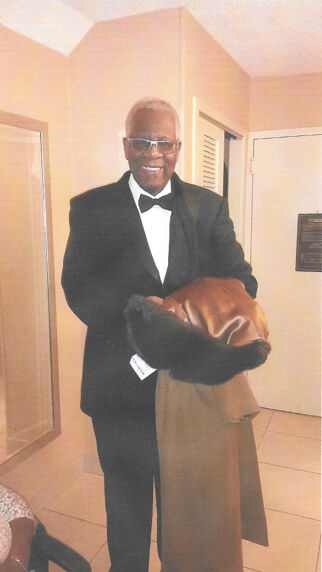

Harvey Clay, 68

Harvey Clay lost his scholarship as a result of the strike because his academics suffered and coaches frowned on his activism. He dropped out of UW–Madison, later taking classes at the University of Hartford in Connecticut and Antioch University New England in New Hampshire. He now owns Real BBQ and More, a restaurant in Shreveport, Louisiana. Customers call him "Papa." He started cooking barbecue in Madison because he couldn’t find any local cuisine to his liking. Yelp reviewers named the restaurant the #26 Best BBQ Joint in the country in 2018.

Frank Emspak, 75

Frank Emspak received his Ph.D. in history from UW–Madison in 1972. He is a professor emeritus in the School for Workers. He founded Workers Independent News, a daily newscast with a 15-year run. At its height, it aired in more than 200 markets. He resides in Madison, where he remains active in social justice causes.

John Felder, 68

John Felder earned a bachelor’s degree in economics history from UW–Madison in 1974. Early in his career, he taught freshmen orientation classes at Hunter College in Manhattan and wrote art criticism for the New York Amsterdam News. He spent 23 years as an administrator with Teamsters Union Local 237 in New York, retiring in 2008 as director of membership. He resides in Brooklyn, New York.

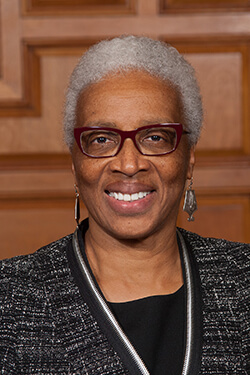

Geraldine Hines, 71

Geraldine Hines graduated from UW Law School in 1971 and went on to become a prominent civil rights attorney and judge. "My whole life's work has been dedicated to social justice," she says. "I went to Madison with the idea that I was going to do that, but what happened at Madison made me more committed to it." In 2014, she was appointed to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, becoming the first African-American woman on the state’s highest court. In 2015, she received a Distinguished Alumni Award from the Wisconsin Alumni Association. She retired in 2017. She resides in Roxbury, Massachusetts.

Donna M. Jones, 68

Donna M. Jones earned a bachelor’s degree in American institutions from UW–Madison in 1972. She went on to graduate from UW Law School and earn a master’s degree in public administration from the Bernard Baruch College at the City University of New York. She served as an assistant to Madison Mayor Joe Sensenbrenner Jr., as the city’s contract compliance officer, and as the affirmative action officer for UW–Madison. She retired from the university in 1995 and resides in Marietta, Georgia.

Liberty Rashad, 70

Liberty Rashad finished the spring semester of 1969 at UW–Madison but did not return in the fall. "There were some things that happened that made us feel unsafe," she says of herself and her husband at the time, fellow strike leader Wahid Rashad. Returning to New York, she continued as an activist, community organizer and youth worker. She raised three sons while earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Marymount University and a master’s degree in educational administration from Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. A retired educator, school director and business owner, she owns and runs Huckabuck Village, a bed and breakfast in the historic Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans.

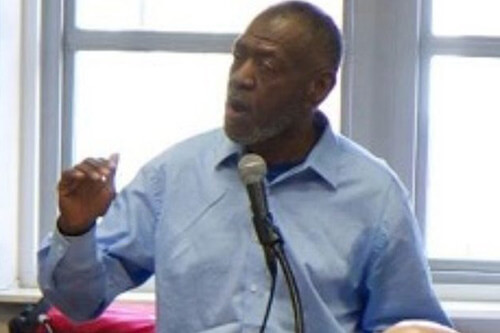

Wahid Rashad, 71

Wahid Rashad did not return to UW–Madison for the fall 1969 semester. "I had a target on my back," he says. "The police knew me. Everyone in the community knew me. I didn’t like the prominence." In 1978, he legally changed his name from Willie Edwards to Wahid Rashad due to his involvement in the Black Muslim movement. His wife became Liberty Rashad. The couple, who raised three sons, divorced in the early 1980s. He became a drug rehabilitation counselor in New York City and was later employed as a work-release counselor for the Baltimore City Jail, then as a sales manager and trainer. Moving to Chicago, where he currently resides, he was employed in the mortgage industry as a broker, trainer and group manager until his retirement.

Hazel Symonette, 72

Hazel Symonette lost the fellowship that supported her Ph.D. work as a result of her participation in the strike. She went on to spend more than 50 years studying and working on the UW–Madison campus, earning two master's degrees at the university, as well as a doctorate in educational policy studies. She founded and directed the Excellence Through Diversity Institute and the Student Success Institute. She works part-time as a specialist in social justice and culturally responsive evaluation at the Wisconsin Center for Education Research and the Division of Diversity, Equity and Educational Achievement on campus. In 2014, she received a City-County Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award for her decades of work on campus and in the community.

Memories

"As someone who grew up in an area with no black population, I was naïve about black concerns. I found the strike very illuminating, and that began my learning process on black issues."

— Patricia Gregg Hesterly, 70, Kapaa, Hawaii

"My roommates and other students and I met communally in my apartment to cook vats of chili to hand out in front of Memorial Union to feed protesters. I boycotted classes and marched with the black students. As a result, I failed my tennis class."

— Gail Auster, 69, New York, New York

"This was by far the most militant (and bloody) demonstration I encountered during my four years at ‘Tear Gas U.’ Entrances to classroom buildings were often physically obstructed. Being the diligent student that I was, on one occasion I got to my calculus class in Van Vleck Hall by climbing through a ground-floor window."

— Norman Dake, 68, Tulsa, Oklahoma

"I grew up in a smallish town in Wisconsin, in a very conservative area of the state. We were taught to trust the government, to fear and hate the Russians, and that the Civil War had freed the slaves. The Black Student Strike had a profound and lasting effect as it opened my eyes to a different reality and raised questions that I would never have even thought to ask."

— Virginia Broomall Weil, 73, St. Louis, Missouri

"I remember black student leadership as the driving force of the strike and a growing understanding of how all oppression was connected. I felt good that the white students, like myself, were supporting this strike. My time in Madison was life-changing and shaped my politics and world view to this day."

— Phyllis Kirson, 69, Fairfax, California

"Day after day of lectures and discussions profoundly schooled me in the depths of institutional racism, a lesson that has affected both my professional and personal life across these 50 years."

— Ruth Ruttenberg, 70, Northfield, Vermont

"I became very proud of UW and its role in respecting and promoting diverse student activists (whom I admired greatly) because those laudable policies enrich the people and the purposes of the academy. I am a better person because of those strikes."

— C. Richard Tracy, 75, Reno, Nevada

Events & Education

Events

-

Feb

11A Recollection of the 1969 Black Student Strike

Panel discussion featuring several participants from this story. Monday, Feb. 11, from 5 to 7 p.m. at the Play Circle in Memorial Union; reception to follow from 7 to 8:30 p.m. at the Black Cultural Center. View the video

-

Feb

20UW Law School Brittingham Distinguished Visitor Geraldine Hines

Wednesday, Feb. 20, from 4 to 6 p.m.

Room 2260, Law School

Resources

Teaching kit: Rena Yehuda Newman, 2018-19 student historian in residence at UW Archives.

"Their Time & Their Legacy: African American Activism in the Black Campus Movement at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Its Enduring Impulse," Ph.D. thesis by Cornelius K. Gilbert, 2011. Available at Memorial Library and online with a NetID.

Madison in the Sixties by Madison historian Stu Levitan.

A Turning Point: Six Stories from the Dow Chemical Protests on Campus

UW Archives: Photos, recordings, documents and more on the Black Student Strike.

About

This story was produced in 2019 by University Communications and University Marketing in partnership with the Black Cultural Center and The Black Voice, a student-run publication. Special thanks to Assistant Director of Cultural Programming Karla Foster and BCC Program Coordinator Lauren Adams for their enthusiasm, wisdom and assistance throughout this effort.

With the help of the Wisconsin Foundation and Alumni Association, we solicited memories from students who were on campus in 1969. We received a strong response from alumni all over the world and are grateful to everyone who took the time to share their recollections.

Interviews were conducted by student journalists Fatoumata Ceesay, Shiloah Coley, Trinity Cross, Chelsea Hylton, Nile Lansana, Alexandria Millet, Summer Mitchell, Enjoyiana Nururdin, Kingsley Pissang and Breanna Taylor and by University Communications staff writer Doug Erickson. Transcripts and audio recordings will be shared with University Archives for its permanent collection.

View videos of the journalists discussing what they learned: Shiloah Coley – video one, Shiloah Coley – video two, Chelsea Hylton, and Nile Lansana.

Newspaper sources included the Wisconsin State Journal, the Milwaukee Journal, the Milwaukee Sentinel and the Daily Cardinal.

John Wolf ’71, who was a graduate student at the time of the strike, provided several of his never-before-published photos. University Communications staff photographer Bryce Richter made portraits of several participants. The photos in the timeline depict scenes from the Black Student Strike in general, not necessarily an event on that day.

Cat Phan and Troy Reeves at UW Archives, Tanika Apaloo and Paul Hedges at the Wisconsin Historical Society and Dennis McCormick at the Wisconsin State Journal provided great help locating and identifying archival materials.

Editors: Bill Graf, Mike Klein, Meredith McGlone

Web design and production: Linda Kietzer, Joyce Johnston, Libby Peterek, Julie Schroeder

Ten UW–Madison student journalists conducted a majority of the interviews for the oral history of the Black Student Strike of 1969. Back row from left, Breanna Taylor, Shiloah Coley, Enjoyiana Nururdin; front row from left, Alexandria Millet, Summer Mitchell, Nile Lansana, Chelsea Hylton. Not pictured: Fatoumata Ceesay, Trinity Cross, Kingsley Pissang. Photo by Andy Manis