The real costs of research funding cuts

With proposed changes to NIH support, critical health research at UW–Madison would be at risk. Here’s why.

Research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison drives innovation, saves lives, creates jobs, supports small businesses, and fuels the industries that keep America competitive and secure. It makes the U.S.—and Wisconsin—stronger. Federal funding for research is a high-return investment that’s worth fighting for. Learn more about the impact of UW–Madison’s federally funded research and how you can help.

Barbara Smith Ballen began traveling to the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus last year to receive brain scans and blood draws, not as a medical patient but as a research participant. She’s part of an ambitious and potentially transformative study aimed at better understanding Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. A mother of five in her 70s, Smith Ballen was motivated to make the regular trek to UW–Madison because of her family history with dementia. She witnessed her father’s struggle in the years prior to his death.

Smith Ballen wants to help UW–Madison researchers find effective treatments for dementia and perhaps even a cure — if not for her dad, then for all future patients and families whose lives are forever changed by the diagnosis.

“I am committed to doing whatever I can to help end this devastating disease and hopefully others will follow my lead,” Smith Ballen said when the project began in October 2024. “I truly believe that this research team has what it takes to make a breakthrough; they just need to stay persistent.”

Now, UW–Madison’s ability to continue such research faces uncertainty. That’s due to a new federal policy from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which is the study’s primary funder and the largest source of biomedical research funding in the United States.

In February, the agency announced a new cap on a form of supplemental funding that supports the infrastructure and workforce necessary to carry out complex research at institutions like UW–Madison. The new cap is much lower than the rate that the university previously negotiated with the NIH, meaning that it stands to lose tens of millions of dollars in annual research support.

But it’s not really the money that’s at stake. It’s what that reliable funding enables: the ability to advance life-saving research and innovation.

The ins and outs of ‘indirects’ funding

The cuts proposed by NIH relate to a funding stream known as indirect costs, or simply “indirects.” They represent supplemental support on top of the funding that NIH sends directly to researchers who have been awarded grants. At UW–Madison and other research institutions, these indirects are crucial to sustaining research on Alzheimer’s, cancer, diabetes and other critical diseases.

Before February, the system for negotiating NIH indirects had been in place for decades, providing institutions like UW–Madison a predictable funding model to plan investments in the buildings, equipment, service contracts and personnel required to carry out cutting-edge biomedical research.

Under that system, each institution negotiated an indirect rate with the NIH every few years. Negotiated rates range considerably among institutions because they depend on variables like the local cost of living, maintenance and service contract fees, and the complexity of the institution’s research portfolio. UW–Madison’s most recent negotiated rate of 55.5% to support research facilities and administration was near the median among institutions nationally. That rate meant the university would receive 55.5 cents of indirect support from the NIH for every dollar of direct grant funding the agency awarded to affiliated researchers. In February, the NIH imposed a cap of 15% for indirect funds across all institutions, which has since been blocked in federal court and continues to be litigated.

The proposed rate cut from 55.5% to 15% would have wide-ranging and potentially devastating consequences for essential research at UW–Madison.

Why indirects are indispensable

NIH indirects funding supports UW–Madison’s research enterprise in such fundamental ways that it’s not always obvious even to the faculty, staff and study participants who depend on it.

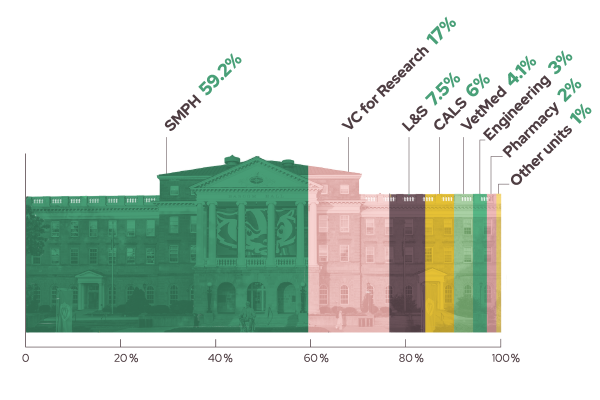

At UW–Madison, the funds are split between central campus, schools and colleges, and departments.

At the campus level, indirects help fund the work of offices that are critical to the safety and wellbeing of researchers and research participants, including functions like biosafety, chemical safety and the Human Research Protection Program. Indirects also fund campuswide functions like building maintenance, utilities, and expensive cybersecurity infrastructure needed to protect sensitive patient data.

Schools and colleges similarly use indirect funds for expenses that might be shared across departments. Take for example the NIH-funded Alzheimer’s study that Smith Ballen participates in: CLARiTI, or Clarity in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Research Through Imaging. The study relies on a maintenance contract for the PET machines used to scan patients’ brains, basic laboratory tools for taking blood samples, and electricity to run the freezers where those samples are stored.

Department-level expenses covered by indirects are typically tied to personnel. NIH grants carry significant regulatory compliance responsibilities, and keeping up with them and the related documentation is a full-time job itself. Some departments with many NIH grants, such as the Department of Medicine, employ dozens of administrative staff who make sure grant requirements are being met and patients are being treated appropriately.

Separately, the huge amounts of data generated by studies require IT infrastructure and data scientists to keep them organized, secure and available for research purposes.

Finally, many large research projects like CLARiTI include hundreds or thousands of patient participants. Dedicated staff are required for scheduling visits and guiding patients through the entirety of their visits.

The true cost

While indirects are critical to UW’s research infrastructure, they don’t fully fund all of these essential functions. The university funds much of the research itself, along with some assistance from private research foundations and other philanthropic sources.

Still, without indirects, it’s easy to imagine how a research study falls apart quickly. Consider what could happen to the safe, efficient and productive experience for a study participant like Smith Ballen.

There may not be staff available to schedule or shepherd her through her visit.

The PET machines might break down due to a lack of maintenance.

The digital brain scans and other sensitive health data could be lost, corrupted or stolen by a bad actor.

And there may not be enough money to purchase and power the freezer storage needed to preserve the blood samples.

UW–Madison’s research enterprise would not collapse overnight from diminished NIH indirects, but the small, compounding effects and long-term consequences could be devastating. Potentially life-saving research would become slower and less ambitious. And the true cost would fall on those waiting for the next medical breakthrough, who would have to wait even longer.