With first graduate, accelerated UW program aggressively takes on physician shortage in rural Wisconsin

Shane Hoffman can see the future he wants clearly: He’s a surgeon at a clinic or small hospital in rural Wisconsin — perhaps somewhere in the far northern part of the state, like Ashland, where his family has deep roots.

His medical practice will allow residents in the area to access care quickly and stay closer to their homes and families while being treated. And when he’s not working, he’ll be near the recreational activities he loves, like hunting and snowmobiling.

“Hospitals are going under because they can’t attract people to these rural communities,” says Hoffman, who grew up near Lake Mills, Wisconsin. “I want to live in a small town or in the country. It’s where I feel most at home.”

Hoffman is passionate about rural health care and on track to be part of the solution to the physician shortage in rural Wisconsin.

On May 9, he will become the first graduate of a program at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health that reduces the time it takes to train doctors interested in serving rural parts of the state. Students in the accelerated program take all the same required courses but graduate in three years instead of four through a combination of factors. For instance, the summer between the first and second years of medical school is traditionally open; these students fill it by immediately jumping into their second-year clinical rotations. The students also have fewer requirements for elective courses, especially those around career exploration, since they’ve already landed on their career path.

The short-track program is a new offering of the UW School of Medicine and Public Health’s Wisconsin Academy for Rural Medicine, known as WARM, which has been successfully addressing the physician shortage in rural areas since 2007. As of this May, WARM will have graduated 327 students. In the past, roughly three-quarters of the graduates have returned to Wisconsin post-residency, with 42% practicing in rural areas.

“There’s a significant geographic disconnect in Wisconsin between where people live and where doctors practice,” says Dr. Joseph Holt, WARM’s director. “As high as 31 percent of the state’s residents live in rural areas, yet only one in 10 physicians practice in these rural areas. It’s imperative that we address this problem because the rural physician shortage is only going to increase as current physicians retire and the population ages.”

Deeply rooted beginnings

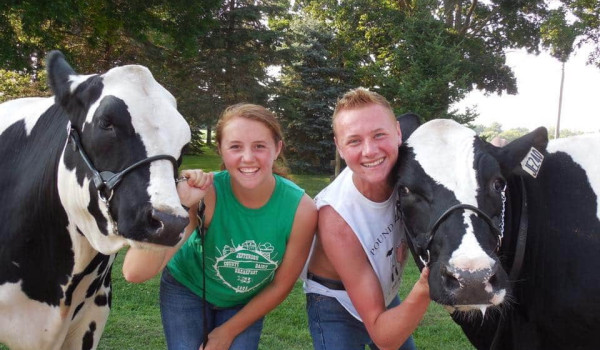

It would be hard to take the country out of Hoffman. Growing up, he raised beef cattle and showed them at the county fair. He got his first snowmobile as a pre-teen and now owns several. He shot his first buck at 12, then another at 13, and another at 14.

“Each time, it was the first bullet — one shot and done,” says his father, Brian Hoffman, a heavy-equipment operator. “I was very proud of him for that.”

Hoffman’s interest in a medical career evolved gradually. His parents point to early interactions with doctors and nurses as influential. In eighth grade, Hoffman broke one arm and sprained the other jumping off a swing. That landed him in the ER at the nearby rural hospital in Fort Atkinson, where he was treated by Dr. Randall Jennings.

“Dr. Jennings had a great bedside manner and explained things to Shane in a way that a kid could understand.” says Hoffman’s mother, Carrie Hoffman, an office manager. “I think that had a big impact on Shane.”

“It definitely influenced my decision,” Shane Hoffman says. “I even wrote about it in my residency application. He talked to me like a person, not just a patient.”

Before medical school, though, Hoffman would go down a couple of other paths.

A ‘major’ breakthrough

As an undergraduate at UW–Madison, Hoffman initially majored in education, thinking he’d teach high school science. But then, as a sophomore, he rolled his snowmobile while racing at the World Championship Vintage Snowmobile Derby in Eagle River, Wisconsin, breaking a hip. The lengthy recovery presented another opportunity to see health care up close. He was impressed with the quality of the nursing care he received, and several nurses encouraged him to consider the field as a career.

He switched his major and earned a nursing degree from UW–Madison. For two years during this time, he portrayed Bucky Badger, UW–Madison’s beloved mascot. His first gig as Bucky, prophetically, was at the School of Medicine’s 2017 Doctor of Medicine Graduate Recognition Ceremony.

Hoffman’s nursing duties took him to a rural hospital in Adams County and to UW Health in Madison, where he worked in the COVID-19 intensive care unit during the early days of the pandemic. As he watched doctors make their rounds, he felt a pull.

“I highly respect the role of nurses, and I enjoyed what I was doing, but I wanted to position myself more as a leader of a team and as someone who could help patients make crucial decisions about their care plans,” Hoffman says.

In the fall of 2022, Hoffman began medical school at UW. It was a nontraditional career move. Only about 2% of registered nurses go on to become doctors, according to current estimates.

Committed to the practice

The goal of the accelerated program at the medical school is to instill in graduates a desire to practice in rural Wisconsin — there are no contracts or other requirements. Hoffman’s clinical rotations as a medical school student took him to rural areas all over the state. What he witnessed only increased his resolve to practice rural medicine.

“It makes me sad to walk through an empty hospital wing,” he says. “People are being shipped to bigger cities because of staff shortages in these rural areas.”

In the days leading up to his May 9 graduation, Hoffman will be finishing his final clinical rotation — two weeks in wound care at Aurora Medical Center–Manitowoc County in Two Rivers. On a recent day, he shadowed Dr. Brett Leiknes. The two have much in common. Both enjoy outdoor hobbies — Leiknes fishes in his off hours — and share an appreciation of rural health care.

“It’s more personable,” Leiknes says. “It’s easier to build relationships with patients in rural areas, and they seem more appreciative of the care they get.”

As they dip in and out of exam rooms, Leiknes encourages Hoffman to ease into appointments by beginning with several minutes of small talk. It’s a tip Hoffman has picked up on many of his rural rotations.

“A lot of these patients are resistant to health care and will see a doctor only as a last resort,” Hoffman says. “I’ve learned that if I take five minutes at the beginning to talk to them, they will be much more likely to tell me what’s really going on.”

Hoffman also has decided to ditch the white coat in rural settings, opting instead for a casual shirt and tennis shoes.

“You’re more approachable if you don’t try to set yourself apart,” he says.

When Hoffman is done with his two-week rotation in Two Rivers, Leiknes will complete his role as the attending physician by reviewing how Hoffman did. Leiknes is already impressed with both Hoffman and the accelerated medical school program.

“I think the program is excellent and exactly what Wisconsin needs,” Leiknes says. “And Shane is clearly an awesome, talented guy. He’s going to do great.”

It’s ‘Dr. Hoffman’ now

After graduation, Hoffman will begin five years of residency. His first year will be spent in several hospitals in Madison. Subsequent years will take him to Neenah and Baldwin, among other sites. Then, he will decide where to put down roots.

“My residency years will be all about putting tools in my belt that I can use in a rural community to hopefully keep that patient in their community or treat them until we can get them to a facility in a bigger city,” he says.

Hoffman will be the first in his family to become a doctor. For his parents, his decision to serve rural patients adds another layer of pride.

“Shane has worked so hard for this,” says his mother. “He would always put in extra hours during his hospital rotations to learn more. Even when they said, ‘Go home,’ he’d say, ‘Well, I want to check on this patient one more time.’”

“I always told him, ‘Don’t forget where you came from,’ and he hasn’t,” says his father, who will be at his son’s commencement ceremony along with many other family members. “I hope I can stop myself from crying. I just can’t believe we get to call him Dr. Hoffman now.”

The Wisconsin Academy for Rural Medicine entering Rural Residency Program (WARMeRR) was launched with the support of a Wisconsin Partnership Program strategic education grant.